Plan B

by Paul Muldoon

reviewed by Heather Clark

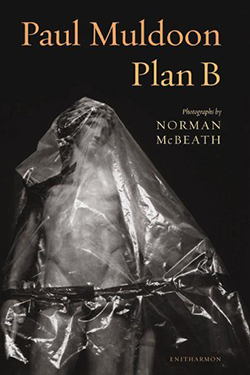

A statue of Apollo covered in polyethylene and duct tape appears on the cover of Paul Muldoon’s Plan B, his recent collaboration with Scottish photographer Norman McBeath. It is an appropriate photograph for a collection that, while marked by Muldoon’s eclectic obliquity, contains a surprisingly somber, even mournful, undercurrent. “It was the photograph of Apollo in transit,” Muldoon writes in his introduction, “that I felt I might be most likely to respond to directly” when he considered collaborating with McBeath. Muldoon called the photograph “kinetic, kinky,” and imagined writing a “kinetic, kinky poem in return.” His lighthearted tone belies the book’s weighty themes, however, which all return, one way or another, to the image on the cover and what it might represent: not simply Apollo in transit, but the Apollonian mind in exile.

Muldoon’s poems are sometimes read as cheeky responses to his former teacher, Seamus Heaney. But the tone in Plan B is reminiscent of another Northern Irish poet, Derek Mahon—particularly his “A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford,” one of the most accomplished poems of the postwar period. In Mahon’s poem, mushrooms, which symbolize victims of “Treblinka and Pompeii,” are discovered after being locked away for half a century. They are wary of their liberators, whom they beg not to “close the door again.” In Plan B, one gets the feeling that Muldoon and McBeath—whose photographs of abandoned buildings, junked pianos, overgrown fields, forgotten cemeteries, and empty rooms suggest disappearances and evictions—are chronicling a similar darkness. Like Mahon, they too ask us to keep the door open.

The collection’s powerful title poem, “Plan B,” weaves together the stories of Edward VII, Topsy the doomed elephant, Thomas Edison, and the speaker, who flits between New York and a former KGB interrogation building in Vilna, site of a notorious Jewish ghetto. In a series of couplet variations, Muldoon creates a dark parable of modernity: colonialism, totalitarianism, exile, torture, genocide, and the sinister uses of technology circle around each other in insistent rhyme. At the poem’s end, Muldoon seems to question the efficacy of poetry itself in the face of such grim realities as the speaker ponders his

perfect deportment all those years I’d skim

over the dying and the dead

looking up to me as if I might at any moment succumb

to the book balanced on my head.

While “Plan B” is the most somber poem in the collection, several others speak to lost potential, whether of John F. Kennedy in “François Boucher: Arion on the Dolphin,” a couple splitting up in “Extraordinary Rendition” and “The Water Cooler,” or a “dying friend” in “A Hare at Aldergrove.” Here, the speaker ruminates on personal loss as well as the larger political situation in Northern Ireland as he sits on a plane at Belfast’s Aldergrove Airport and watches a hare on the runway.

Clapper-lugged, cleft-lipped, he looks for all the world

as if he might never again put up his mitts

despite the fact that he shares a Y chromosome

with Niall of the Nine Hostages,

never again allow his Om

to widen and deepen by such easy stages,

never relaunch his campaign as melanoma has relaunched its campaign

in a friend I once dated,

her pain rising above the collective pain

with which we’ve been inundated

as this one or that has launched an attach

to the slogan of ‘Brits Out’ or ‘Not an Inch’

The friend dying of cancer conjures up images of Mary Farl Powers, Muldoon’s former lover, whom he elegized in his masterful “Incantata.” The looming loss of this other, unnamed friend, as well as Powers’s lost potential and the waste of “the almost weekly atrocity” in Northern Ireland, all culminate in the last few lines. There, the speaker wonders whether

we should continue to tough it out till

something better comes along or settle for this salad of blaeberry and heather

and a hint of common tormentil.

Muldoon has always approached the political situation in Northern Ireland from “an oblique angle,” as Seamus Heaney once put it. One is tempted to read this poem’s ending as such. The “something better” suggests a distant political ideal, whether a united Ireland or a non-sectarian Northern Ireland. The moor plants, on the other hand, invoke a common geography, but of a type that is (literally, here) hard to swallow.

The startling, desolate beauty of McBeath’s photographs, like Pompeii’s ashen figures, is discomfiting in the same way that Muldoon’s unerring, circular rhyme schemes are; the insistence on aural harmony is hard to reconcile with themes of exile, persecution, assassination, war, and lost love. And yet the formal mastery of these poems, most of which are variations on intricate forms such as the rondeau, the villanelle, and the sestina, suggest reinvention and renewal rather than hermetic irony. Despite his misgivings about his own poetry being too artificial (he reminds us, in “Incantata,” that Powers called him “Polyester or Polyurethane”), Muldoon’s unrivaled technical skill, on full display in Plan B, creates a deeply satisfying energy. This energy—both kinetic and kinky, like the iconic image of Marilyn Monroe’s up-blown dress in “A Hare at Aldergrove”—gestures toward hopefulness and humor in the face of anguish. Michael Longley once told Muldoon that he wanted to write “wee poems that move people.” “Believe it or not,” Muldoon responded, “I do too.” Plan B makes that ambition clear.

Published on June 21, 2013