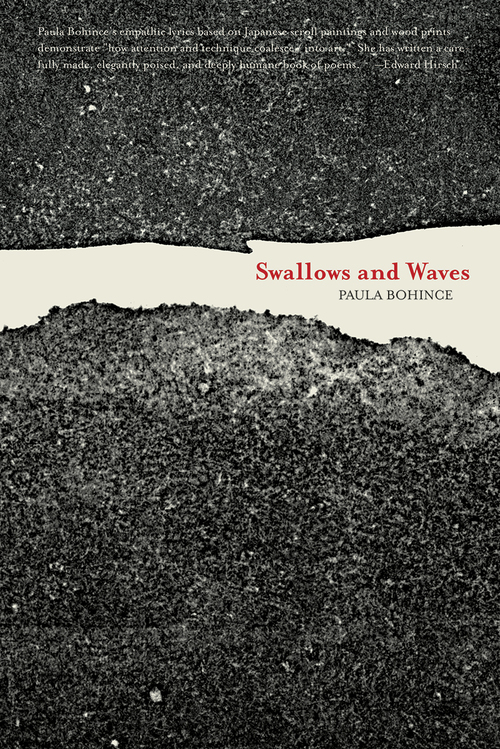

Swallows and Waves

by Paula Bohince

reviewed by Henry Hughes

Ekphrasis seems too sharp a word, consonants clanging together like spears on a shield, to describe the silky music of these elegantly balanced poems based on Japanese scroll paintings and woodblock prints from the Edo period (1603-1868). Just as those timeless images—particularly the ukiyo-e prints of Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Moronobu—worked as poems to crystalize ordinary moments in peoples’ lives and in nature, Paula Bohince’s poems redraw interiors and intimacies of these same experiences, which feel strangely familiar.

In “A Mother Dressing Her Son in a Kimono,” inspired by Suzuki Harunobu’s eighteenth-century colored print, we share a woman’s sexuality reshaped by motherhood. The uncensored description of a maturing son includes the mother’s farewell to the “romance” of nursing.

He stands, suddenly more man than animal,

but naked and bald-headed, his penis a bashful sprig.

Spring has delivered its news. She kneels

and guides sleeves over fresh muscles. Her breasts

retreat back to ornament. The romance of their first

year together, milky nights in bed, quietly ends.

Swallows and Waves shimmers with kimonos, samurai, chrysanthemums, crickets, cranes, and dragons, yet it never feels like manufactured Orientalism. Until this third collection, Bohince had never worked from visual art, let alone art from a distant time and culture, but she found that “deep down these works felt so familiar.” She carefully documents the artwork at the end of the book, establishing authenticity, and in a poem such as “Courtesan with Her Attendant,” we trust her minimal brush strokes and wise expositions: “As imitation bends toward knowledge, so pleasure / becomes a version of love.”

Many Western poets, from Ezra Pound to Gary Synder, have been hopelessly in love with Japanese culture and its exotic erotics, but Bohince joins the very best of writers who slide open the screens, fully aware there are other screens still concealing our deepest pleasures and pains. This notion is beautifully expressed in “Lover Taking Leave of a Courtesan”:

He stands and dresses

but slowly, to show reluctance.

This is dawn’s performance.

She from the spent cushion

grasps his clothing, not

to keep him but to indicate pleasure-

given loyalty.

Fuji is present, as a painted

screen. The real exists, hidden

behind it. The man,

woman are representatives

also, though the pain, the nature

of pain, is personal.

Key to these studies of human behavior poetically interpreted from the archives of Japanese art are the notions of performance and privacy, particularly as they relate to women. Conscious of a patriarchal Edo society where the roles of women were highly restricted by neo-Confucian ethics, Bohince shows us the precious times when women are alone together: undressing, smoking, combing each other’s hair, or leading a horse up a foggy mountain trail with only their “bright kimonos as guides.”

Broad topics

narrow, with no men, no children

listening. Lightheaded as actresses taking off

make-up, they speak as themselves, exhale as clouds

confessions, thoughts undressed, a nakedness . . .

Japanese artists and writers have long understood that family and civic stresses, tightly wrapped in codes of moral conduct, require periodic escapes into solitude or some wilder nature. “Is there a prettier word / than privacy?” Bohince asks in “Maples,” a poem that moves from guilt-soaked contemplation of reddening trees to the necessity of private pillow book confessions. Buddhist and Taoist nature-extolling philosophies that arrived from China, along with illustrated tales of animals, gave rise to paintings such as Komai Genki’s “Tiger Licking Its Leg,” which Bohince breathes to life: “Un-kissed / perhaps since cubhood, / mother long wandered, the mouth asserts calm / assurances all over the chaotic body.” This book teems with glowing fireflies, lugubrious carp, moon-bathed rabbits, and “An Eagle Attacking a Monkey under a Pine Tree,” with its painful social reminder that “Another monkey, high in the pine, must witness.” There are gentler birds, of course, whose strengths nevertheless remind us of our own endeavors and exertions. In the book’s title poem, we can identify with thirteen swallows buffeted by wind and cresting waves from those life-giving yet deadly island seas—“Mist wets their breasts / and makes flying heavy”—yet they endure, enough of them, “minor miracles, granting grace / to that universal struggle.”

Published on November 29, 2016