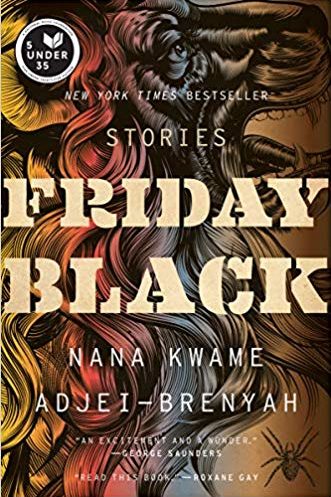

Friday Black

by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

reviewed by Patrick Lohier

The Kendrick Lamar quote that serves as the epigraph of Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s debut short story collection, Friday Black, “Anything you imagine you possess,” evokes the spirit of a promising debut album release. That mood suits this collection, which puts the author’s engaging talent and impressive creative range on full display. Adjei-Brenyah sings tropes of popular culture laced with the soul of the African American and immigrant American experiences. He conveys joy, pain, longing, rage—especially the rage felt by those who experience racism—with talent and force, writing through genres and styles ranging from the fantastical to the cartoonish, the dystopian, the morbidly stark and the surreal.

A few of the stories—“Friday Black,” “In Retail” and “How to Sell a Jacket as Told by IceKing”—confront consumerism with razor-sharp satire. In Adjei-Brenyah’s world the workers of the Prominent Mall routinely mop up pools of blood following store-aisle riots: “It isn’t always like this,” says the narrator of “Friday Black.” “This is the Black Weekend. Other times, if somebody dies, at least a clean-up crew comes with a tarp.”

Some of the stories have an almost Black Mirror-like tone. “Zimmer Land” takes its title from the name of a tech startup that offers fully immersive, virtual “safe space[s]” in which adults can “explore problem-solving, justice, and judgment.” Players enter different modules that allow them to experience vividly realistic scenarios, sometimes requiring life or death decision-making. The greatest illusion of the technology may be that it can offer experience without consequence. Isaiah, one of Zimmer Land’s few African American employees, acts out parts in the modules, including one called “Cassidy Lane,” in which players confront an anonymous black youth on the street. Isaiah feels loyal to his employer, but he’s also highly attuned to the social and ethical complexities and implications of Zimmer Land’s services. As the black youth in “Cassidy Lane,” Isaiah observes the zeal with which many customers (who are armed in the module) escalate the otherwise innocuous encounter as if intent less on “problem solving” than on aggressive confrontation and even murder.

In “The Hospital Where,” the unnamed narrator’s father goes to a hospital because of seemingly simple arm pain. “This was all long before he knew of the cancer nesting in his bones,” the narrator says of his father. He goes on to reveal the psychic scars of his immigrant family’s long-suffered poverty; in their basement apartment “[d]ark mold had to be attacked with bleach regularly. But it never died. I hated this place we lived in and had for a very long time.” An aspiring writer, the narrator becomes increasingly desperate during the hospital visit, driven by a prescient terror of what’s in store for his father. At the same time, he’s obsessively focused on nurturing his newly reawakened creativity. “I had no command over the place or the people in it. And yet, for the first time in more than three weeks, I felt the mark of the Twelve-tongued God, an X followed by two vertical slashes, burning in my back. My muse, my power, was awake again.”

Slowly, we come to understand that the “God” is the daemon or deity behind a kind of Faustian pact. “Aren’t I the one who made you something?” the god taunts the narrator. “Or maybe you’d rather cook on a hot plate for the rest of your life?” The story takes a surreal turn as the narrator starts to wield his powers like a wizard. He bends the story to his desired outcome, generously dispensing freedom and reprieve from illness, fear and death, leading to a spectacular final image that serves as an enchanting yet bittersweet testament to both the powers and the limits of art. After graduating from SUNY Albany, Adjei-Brenyah went on to receive his MFA from Syracuse University. It’s tempting to imagine that the narrator of “The Hospital Where” is a version of the author, the struggling and ambitious artist as a young man.

A few of the stories fall flat or are so tonally different that they might have been better served in a different collection. “Light Spitter”, for example, is the story of a school shooter and his victim, and their after-life collaboration to stave off yet another act of violence. The story is ambitious as a concept but succumbs to its cinematic conceit. “Things My Mother Said” and “The Lion & the Spider” feel, like “The Hospital Where,” deeply personal and intimate, but fall short in that they don’t fully engage in the fantastical flourishes that characterize Adjei-Brenyah’s other stories. But most succeed, memorably, because Adjei-Brenyah’s primary focus is on the human heart in our times, and the challenges of race, immigration, violence and increasing wealth and resource disparity that we now face. It will be interesting to watch his writing develop and evolve as he explores our most cherished desires, fears, goals and anxieties with passion and a unique vision.

Published on May 14, 2019