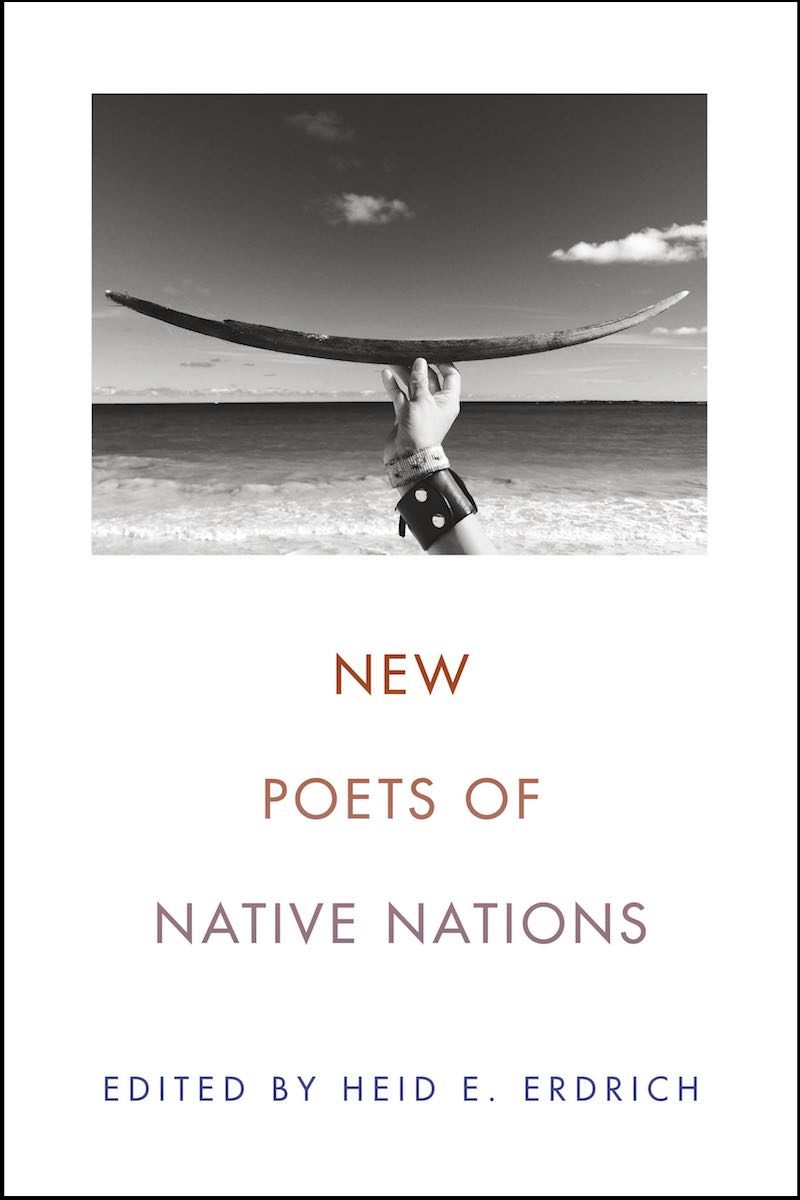

New Poets of Native Nations

edited by Heid E. Erdrich

reviewed by Leah Silvieus

“These poems create a place, somewhere we could go,” editor Heid E. Erdrich writes in her introduction to New Poets of Native Nations. The idea for the anthology began, Erdrich recounts, after she encountered a prominent literary critic’s social media post asking for names of contemporary Native American poets, which received “very few names of poets from specific Native nations in response.” This led her to the realization that “we Native Americans writing poetry are dangerously obscure and—worse again—obscured by poets who are not Native to any indigenous nation.”

While the aim of the collection is to introduce a contemporary audience to the range of new voices in Native poetry, Erdrich is careful not to equate “new” with only “young” writers, noting that the “‘new’ in the title relates to being new to book publication in the twenty-first century.” Within this framework, the anthology brings together poets whose work I was already familiar with, such as Natalie Diaz and Layli Long Soldier, as well as voices that I hadn’t encountered before. Among them is M.L. Smoker, of the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes of the Fort Peck Reservation in northeastern Montana, whose lyrical meditations on the confluence of of natural and interior landscapes at times recall that of fellow northwest poet Richard Hugo. For example, as Smoker writes in “Crosscurrent”:

And the last road you know as well as I do—

past the coral-painted Catholic church, its doors

long ago sealed shut to the mouth of Mission Canyon,

then south just a ways, to where the Rockies cut open

and forgive.

The collection includes between nine to fifteen pages of work per poet. Allowing this much space for each poet provides the reader an in-depth impression of each poet’s voice and poetic concerns, whether the poet tends to work in terser forms, such as Trevino L. Brings Plenty, who has nine poems included in the anthology, or Tommy Pico, whose section includes lengthy excerpts from his three book-length poems: IRL, Nature Poem, and Junk.

New Poets of Native Nations also provides an impressive range of poetic voices and styles, including terse lyric poems alongside lengthier poems like Layli Long Soldier’s six-page-long “38,” which serves both as a retelling of the story of the “Dakota 38,” the 38 Dakota men who were executed by hanging under orders from President Lincoln after the Sioux Uprising. The poem’s expansive form allows the speaker to interrogate the ways in which historical narratives are told in the U.S.: Who is empowered to tell which stories? To which audiences? To what ends? What are the linguistic and syntactical mechanisms by which these stories use to serve those ends?

You may like to know, I do not consider this a “creative piece.”

I do not regard this as a poem of great imagination or a work of fiction.

Also, historical events will not be dramatized for an “interesting” read.

Therefore, I feel most responsible to the orderly sentence; conveyor of

thought.

The anthology also makes space for hybrid forms such as Leanne Howe’s “Catafalque” series, in the form of a conversation between Mary Todd Lincoln and the “Savage Indian” who she, as Howe recounts in her author notes, “invented to torture her in Bellevue Place in Batavia, Illinois.”

The risk in devoting so many pages to each poet, of course, is compromising breadth for depth, but New Poets of Native Nations does not claim to be comprehensive—with more than 566 Native nations in the U.S., such a project would require volumes. Instead, the anthology provides an entryway to the wide range of Native poetry that exists, not only through the poems themselves but also via the author notes at the end of the anthology, which include further reading recommendations, insights into the writers’ own journeys into poetry, and their relationships to their tribal languages. The notes are range stylistically from short, direct recountings of the steps by which the authors’ first books came to be published to lyrical considerations of the writers’ poetics, as Margaret Noodin’s notes exemplify:

Akawe nind’anishinaabebiige apane. I always write first in Ashinaabemowin.

Nind’ozhibii’igemin ji-nanaakwiiyang gaye ji-nanaa’imang akiing miinawaa

ji-abamiitawyang gaye abaakaawiyang. We write to resist and repair the

world, to rise up and be renewed.

Many collections of Native poetry, as Erdrich notes, are published by university presses and available to small audiences. Further, she explains, Native poetry edited and selected by non-Natives is often presented “within binary notions of an easily digestible ‘American Indian’ history or tradition in order to tie contemporary to past in a kind of a literary anthropology,” thus excluding writers who do not neatly fit into often stereotypical notions of what Native poetry should be. As Erdrich writes, this anthology works against these stereotypes and “stands in relation to generations, but it does not bow to that context.”

In her introduction, Erdrich writes that one of her aims for the anthology was to add to a body of literature that allows Natives to be visible “in the world we all inhabit now,” a goal in which the anthology thoroughly succeeds both in terms of the work it includes and the doors it opens for increased visibility for Native writers, whose work already speaks for itself. Or, in the words of Eric Gansworth’s “Repatriating Ourselves”:

There is no need

for you to give

back to us

what we already ownThis is who we are

in the present

tense

Published on April 11, 2019