Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure

by Artemis Cooper

reviewed by Laura Albritton

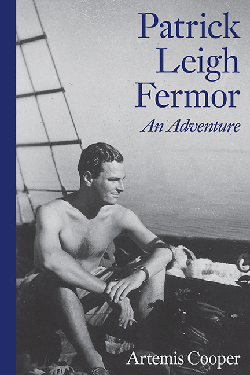

The cover of Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure is an excellent introduction to its subject. Leigh Fermor sits on deck with the sea behind him, his chest bare, cigarette casually in hand, his gaze focused on the discoveries ahead. By anyone’s estimation, Patrick Leigh Fermor’s life was an extraordinary adventure. His biographer, Artemis Cooper, has the advantage of having known him; she is also the granddaughter of Lady Diana Cooper, who carried on a great correspondence with him. As a result, she seems very much at ease with her subject, referring to him as “Paddy” throughout.

Leigh Fermor came to fame in the U.K. for his daring exploits in the Second World War and for a series of beautifully written travel books, including The Traveller’s Tree, Roumeli, Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese, A Time of Gifts, and Between the Woods and the Water. As a teenager at King’s School, Canterbury, he learned Greek but was eventually thrown out. His housemaster reported that, “He is a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness which makes one anxious about his influence on other boys.” A devotion to Greece, the pursuit of women, recklessness, and an irresistible charisma became defining elements in Paddy’s life.

Leigh Fermor’s originality becomes clear when, with no prospect of attending university, he decides to walk across Europe to Constantinople. Cooper does excellent work researching his trek (which Leigh Fermor himself chronicled in two volumes). She quotes from his diary and introduces us to the people he met, many of them members of the faded aristocracy. People welcome him because: “In Paddy’s company everyone felt livelier, funnier and more entertaining.”

Abroad, Leigh Fermor uncovers a world that seems preserved in amber, with intimations of the terrible events to come, including a pervasive anti-Semitism. In Athens he meets the cultivated and older Romanian painter Princess Balasha Cantacuzene and becomes her lover. He spends a year on her family’s dilapidated Romanian estate, Balani, after which he and Balasha move between London, Greece, and Romania. Cooper notes that:

Living with the Cantacuzenes in Rumania had granted Paddy several of the opportunities afforded by a university education . . . he had learnt Rumanian, studied its history, and read as much as he could in that language and French. Above all, Balasha and the Cantacuzenes had given him . . . a set of people among whom he felt he belonged and was understood.

Later, during World War II, Leigh Fermor was given a commission in the Intelligence Corps based on his skill with foreign languages: “He would be in Crete, out of uniform, living in the open, in constant danger.” Cooper supplies us with welcome context, from the political to the geological, though the initial passages chronicling Paddy’s war work lag in places due to too many actors. “The Hussar Stunt,” however, is nail-biting. With the aid of fearless Cretan partisans, Leigh Fermor and a few Brits capture German General Kreipe and sneak him off the island in a boat to Cairo. Their improbable success later inspires books and even a film.

After the suspense of the Cretan episodes, Cooper keeps things lively as she recounts Paddy’s meeting with his future wife, the photographer Joan Rayner (née Eyres Monsell), and his friendship with figures like Lawrence Durrell. Leigh Fermor had a relentless curiosity, traveling to the French West Indies (inspiration for his only novel, The Violins of Saint-Jacques) and to Haiti (inspiration for The Traveller’s Tree). Here, Cooper reveals some of Leigh Fermor’s unpublished judgments: “All the Caribbean islands have something wrong with them,” he wrote. “All are founded on bloodshed and slavery, and are now miserable, subsidized, impoverished places.”

Greece remains a central organizing principle in Leigh Fermor’s life, and Cooper does a fine job of weaving tumultuous Greek politics through his personal chronology. He and Joan eventually build their dream house in Kardamyli. Writing, however, was sometimes a torture, as Cooper observes: “He set great store by the initial surge of writing . . . Yet the moments of creative possession, when the self is lost and time becomes meaningless, were rare.”

As a biographer Cooper shows little interest in psychoanalyzing her subject. On one hand, this shows admirable restraint; on the other, Leigh Fermor remains enigmatic. We wonder, for example, how exactly he became so erudite. Leigh Fermor and his wife maintain an open marriage, but their motivations and emotions are often left unexplored. Elsewhere, Cooper points out that the Duchess of Devonshire adored him, but we’re given only glimpses of his charisma.

Cooper does, however, add a great deal in terms of tracing the trajectory of Leigh Fermor’s life, pinning down facts (as opposed to myths), providing historic context, and quoting from diaries and letters. The result, even with unanswered questions, is an excellent read and should revive interest in his writing. For that we owe Artemis Cooper a debt of gratitude.

Published on May 22, 2014