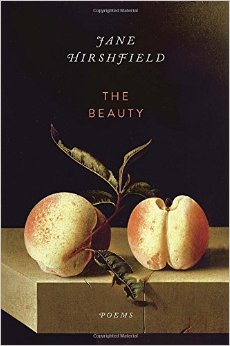

The Beauty

by Jane Hirshfield

reviewed by Henry Hughes

What’s the chance you would open Jane Hirshfield’s hundred-page eighth collection of poetry to “The One Not Chosen”? Maybe you don’t read much poetry—that would certainly reduce the chances—but Hirshfield’s recent interview on NPR and her national reputation as a poet, Zen practioner, literary critic, translator, and tireless champion of women and art may have drawn you to this book and perhaps this poem:

Third sister,

aunt one forgets to send a card to.Boy on a bench, second smallest . . .

Culled chick, branch-bruised peach,

chair wobbly, unused, set in a corner.

Accessible and relatable, the discussion deepens to a notion of chance, dread, even guilty embrace.

the thirty-year-buried land mine

chooses the leg of another.

(How the mouth struggles

to say it: lucky, good.)

In a move that first surfaced in the nature-focused poetry Of Gravity & Angels (1988) and later The October Palace (1994), Hirshfield critiques human self-centeredness by plunging into an animal. Meet the rabbit:

It looks out its ground-level eyes,

is warm, is curious, hungry,

its heart beats faster or slower

with its own rabbit fate.A rabbit’s soul cannot help

but choose its own ears, its own paws,

its own startlement, sleepiness, longings,

it has a rabbit allegiance.

Hirshfield asks us to reimagine the concept of identity and soul—rabbitness—and its relationship to human language and our basic need to accept and reject things about our universe. The Beauty is packed with statements about choice, including: “perfume / that does not choose the direction it travels” or “Has an electron never refused / the invitation to change direction . . . ?” Fortunately, the philosophical inquiries touch ground with the image of the rabbit’s pink nose, before sending us out into the cosmos, where it

pinkly alters the distant star’s light

in its own cuniculan corner

among vast and unanswerable worlds,

without even knowing it does so.

Outer and inner realms are beautifully traversed in this book, though, like Mary Oliver, Hirshfield occasionally treats nature as an overly precious, ever-glowing entity, and she often depends more on stated attitude than exploratory language for her poetic charge. But when the balance of showing and telling, concrete and abstract, actual and surreal is right, few living poets write better. Hirshfield’s rigorous creative life and the study and practice of Buddhism have brought her to a high and confident place. With confidence comes wit and pleasure, and many of these poems are refreshingly clever and fun. In the comma-clipped “This Morning, I Wanted Four Legs,” the speaker claims,

Nothing on two legs weighs much,

or can.

An elephant, a donkey, even a cookstove—

those legs, a person can stand on.

Two legs pitch you forward.

Two legs tire.

They look for another two legs to be with,

to move one set forward to music

while letting the other move back.

I read this poem to a room of children and adults. Everyone seemed enchanted, though the kids yelled “What about kangaroos?”

But even the more complex poems in this collection do not surrender their playful self-awareness. In a series of pieces including “My Skeleton,” “My Proteins,” “My Eyes,” “My Memory,” and “My Sandwich,” we find “My Species,” an honest, hopeful, and thoroughly poetic take on the human race.

even

a small purple artichoke

boiled

in its own bittered

and darkening

waters

grows tender,

grows tender and sweetpatience, I think,

my specieskeep testing the spiny leaves

the spiny heart

“I profess the uncertain / with gratitude,” the poet tells us late in the book. Maybe understanding is overrated, though many of these poems are generously and beautifully rewarding in that way. As for the tricky pieces, Hirshfield seems quite aware of their possibilities and limitations: “Riddles are soulless / In them, it is never raining.”

Published on December 1, 2015