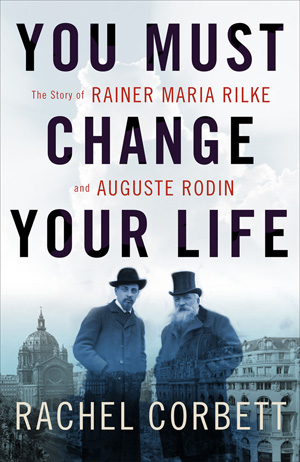

You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin

by Rachel Corbett

reviewed by Erik Hage

One of the more interesting psychological approaches to close relationships is self-expansion theory, which holds that individuals have a fundamental motivation to expand—and that one of the ways in which they achieve this is through the formation of close bonds with others. This theory is often applied to friendships between creative pairs. One can see, for example, how poet Emily Dickinson, in fusing herself to writer and activist Robert Wentworth Higginson through letters, sought to absorb his perspectives and knowledge as a means of fostering her own growth. There are many other examples in literature: Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne, for example, or Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell.

Rachel Corbett doesn’t cite self-expansion theory in her penetrating and teeming book You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin, but this critical biography is very much about the creative expansion of the Prague-born Rilke, who was still a struggling poet in his twenties when he came under the spell of French sculptor Auguste Rodin, then a lionized master in his sixties.

Rilke first met Rodin in 1902 after being commissioned to write a monograph of the sculptor. He approached the artist as a biographer and critic, probing his worldview and his works. A few years later, he became Rodin’s personal secretary. But it is Rilke’s inner life and development that is the main subject of this book. Rilke, under the spell of Rodin, attempts, in Corbett’s words, a “kind of alchemy of mediums”—that is, he seeks to merge Rodin’s artistic perspectives and intentions into poetic form.

Immersed in his study of the sculptor, Rilke unfolds within himself. As Corbett tells it, “He had observed and considered Rodin’s art from every angle and it had changed the way he saw the world.” Despite somewhat of a language barrier—Rodin spoke only French, and the German-speaking Rilke was still learning the Gallic tongue—Rodin framed out lessons for the younger man, the most pressing being “Travailler, toujours travailler. You must work, always work.” Such was the impact of Rodin that one can trace many of his lessons in the pages of Letters to a Young Poet, the widely read collection of Rilke’s advice to Franz Xaver Kappus.

Corbett’s lithe prose animates Rodin’s artistry, too: “Rodin manipulated light to enhance the sense of movement in his figures,” she writes. “When the geometry of the planes aligned just right, light would coast and dart across the surfaces and create the illusion of motion.” She is equally adept at rendering the two men in physical space, her writing suggesting Rodin’s own work. “[Rilke’s] face gathered to a point right where his nose joined a few droopy whiskers. He was twenty-six years old, narrow-shouldered and anemic, while the stout Rodin, then sixty-one, plodded around heavily, his long beard seeming to draw him even closer to the ground.”

Corbett synthesizes her rigorous and far-reaching research into a narrative that spins well beyond Rilke’s development and the sometimes turbulent relationship with his mentor, while still remaining grounded in that reality. Multiple historical contexts serve the story: Fin-de-siècle Europe, the dawning of Freudian psychology, the advent of movements such as Cubism and Expressionism, the urban phantasmagoria of pre-World-War-I Paris, and the cataclysmic war itself. Corbett also draws us into the later lives of the two men, particularly that of Rilke who, having eventually entered the rarified air of his own creative success, often denied that he was ever secretary to the legendary sculptor. She is also frank about Rodin’s chauvinism and erotic fixations—and about Rilke’s strange, sad solitude.

This is a vibrant, clear, and intelligent work, and Corbett, an executive editor of Modern Painters, has taken hold of a great topic. This is a relationship that has not been thoroughly explored before, but she also understands that the intimate dynamics of the bond itself can’t sustain a lively and fully fleshed-out book. Rather, Rilke’s development becomes the whirlpool’s center, with so much more circulating around it, including Rodin.

The concept of empathy is central to You Must Change Your Life, both as an emerging art philosophy and as a subject for psychologists in the early twentieth century. Empathy draws Rilke into a deep understanding of Rodin and his art and fosters his own self-expansion. Similarly, Corbett’s deeply empathetic perspective illuminates Rilke’s development in its many shades.

Published on January 24, 2017