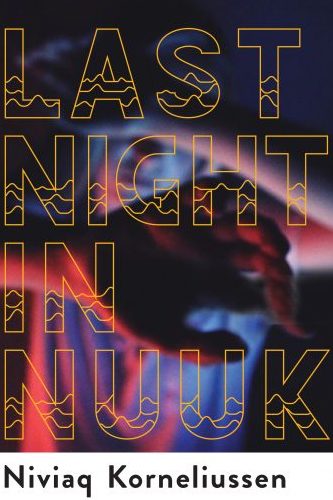

Last Night in Nuuk

by Niviaq Korneliussen, translated by Anna Halagar

reviewed by Erica X Eisen

Soon after it came out in its writer’s native Greenland, Niviaq Korneliussen’s debut novel Last Night in Nuuk (the title of which exists in multiple instantiations—its Greenlandic original is Homo Sapienne, while the UK version is Crimson) shot to the top of the country’s best sellers list, launching its twenty-seven-year-old author to the forefront of her nation’s literary scene. Prior to the book’s English-language release, Korneliussen was profiled in The New Yorker; Sjón, an Icelandic writer perhaps best known for his collaborations with Björk, ranked Last Night in Nuuk among the top ten modern Nordic books in an article for The Guardian, placing Korneliussen among such august company as Tomas Tranströmer and Dag Solstad. Amber Wheeler Bacon, reviewing the translation for Ploughshares, called it “powerful, emotionally dense, and over much more quickly than I wanted it to be.”

I must write against this praise. Korneliussen’s novel, a story of love and heartbreak and queerness that bobs and weaves between narrators, represents a watershed moment for Greenlandic literature in its frank treatment of sexuality, LGBTQ issues, and youthful disaffection. Fia, our first narrator, breaks up with her dull boyfriend and falls for Sara; Inuk, Fia’s brother, goes from condemning his sister’s lesbianism to accepting his own homosexuality after being outed by his best friend, Arnaq; after Ivik and Sara break up, Ivik comes to realize that he is trans. It’s unfortunate, however, that a national literature’s thematic breakthrough should come in so disappointing a stylistic package.

The prose of Last Night in Nuuk—which seems to have required some creative formatting to achieve full novel length—is loose and direct, making liberal use of fragments and repetition (“When it was time, Inuk, I, [sic] came home. Home is in me. Home is me. I am: home”). But the first-person narration combined with the naked emotionality and the narrow focus on relationships frequently lends the text an unwelcome teenage diary feel (“Angry people make me angry. The simmering anger makes me angry. The mounting anger makes me angry. Anger makes me angry. I’m angry at my anger”). Adding to this effect is Korneliussen’s extensive use of text message screenshots and other iPhone-inflected formal choices. The subsections of the last chapter, narrated by Sara, end in hashtag sum-ups (“#chance #change,” “#calmbeforethestorm” “#welcomebacktolife”); Inuk ends each of his narrative chunks by giving a Rupi Kaur-esque label to his emotional state (“survivor,” “silent,” “lost”). These superfluous elements reflect the modern world without reflecting upon it: rather than complicating our understanding of how technology mediates communication, they merely flatten the action and leave readers with the unpleasant sensation that the author assumed they would need such extensive signposting.

More problematic than the failed formal experiments, however, is the fact that Korneliussen’s novel presents us with holes where characters should be, which makes it difficult to invest in the drama or even to distinguish the narrative voices through which the novel shifts. We know, vaguely, the characters’ relationships to one another; we know, vaguely, some of their occupations (Arnaq and Ivik are ex-journalists, though what Fia and Sara do to keep body and soul together is never specified). But as for quirks, as for tics, as for any richness of past, present, or hopes for the future, as for any vibrant emotional life, Korneliussen draws a frustrating blank. The few splashes of detail—Fia and Ivik watched Free Willy together growing up, Fia once made Ivik cry when they were little—hew disappointingly to the generic. Even the names themselves are deliberately imprecise: Arnaq means woman, while Ivik simply means human. The presence of a list of dramatis personae at the beginning seems an admission that without these bios, readers would be able to gather very little about the characters from the text alone.

One could make the case that the lack of individuating detail is an attempt by Korneliussen to make characters with frequently marginalized sexual and gender identities universally relatable. But the unpalatable premise inherent in such a line of argument is that in order to craft characters with whom readers can connect one must present them as blank-faced men and women without qualities. If we cannot use writing to create understanding—even love—between a reader and a character from a different world, then literature as a project has failed. Above all, Korneliussen could do with a greater degree of faith in her readers’ capacity for empathy. It is perfectly possible to feel compassion for a person with wildly different experiences, beliefs, and desires—but it is impossible to feel compassion for a void.

Published on May 21, 2019