The Babysitter at Rest

by Jen George

reviewed by Jennifer Kurdyla

We meet the first narrator, one of several loosely interchangeable female voices, of Jen George’s deliciously subversive collection of linked stories when she’s thirty-three years old. The age Jesus Christ was when He was crucified; the age when, according to some, one comes fully into adulthood and gains a sense of one’s identity. But this young woman is far from having anything you might call an “identity”; rather, a Guide has been hired to train her to become an adult, proclaiming, “We find you at the point of early decay. Decay sets in with the loss of possibility, not having children, having children, a string of failures over years, memories, jobs, aging, becoming out-of-shape, losing your looks, realizing you’re a one-trick pony or fraud or nothing special, and understanding things too late.”

At least Jesus knew He was going on to greater things.

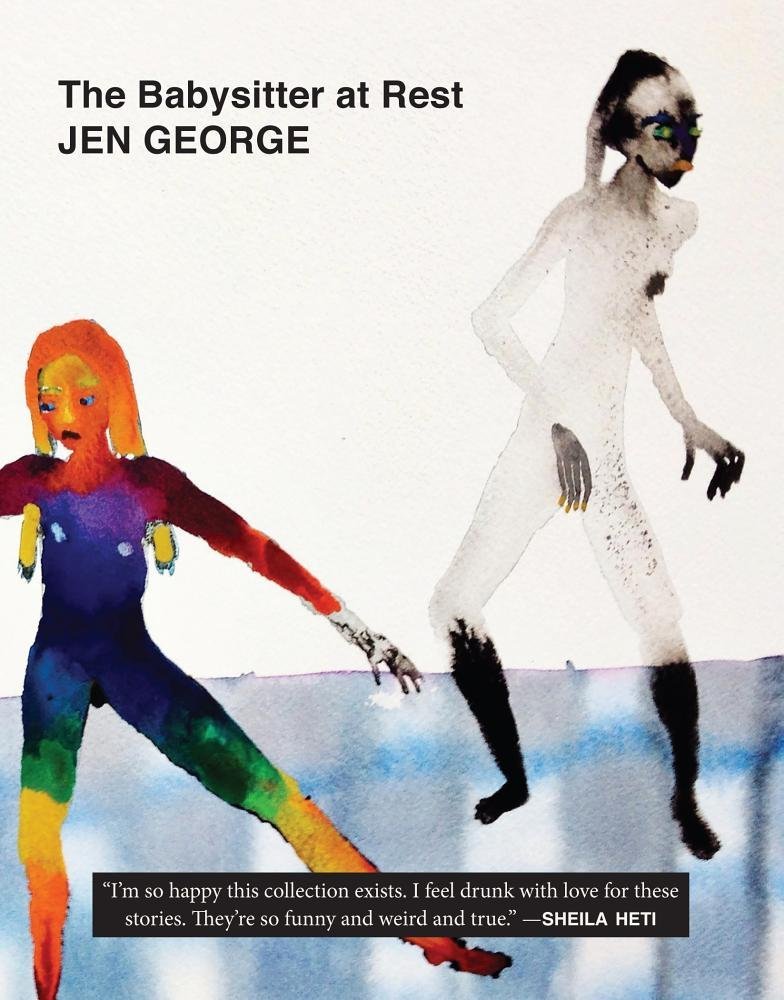

Despite this disarmingly fatalistic setup of the real-life condition of the entire generation of young women living today presented at its outset, The Babysitter at Rest does ultimately redeem itself with its unconventional style and inventiveness. George’s voice deftly shifts between her women’s points of view and different narrative modes, all of which ooze deadpan sarcasm and wit such that you can’t help but laugh. The fact that the reader is laughing as much at the characters as she is at herself adds a layer of keen self-awareness to the book that, like Shelia Heti’s novel-from-life How Should a Person Be?, puts it in the camp of recent fiction that connivingly blurs the line between imagination and truth. As even the title and jacket art provocatively suggest, this multifaceted portrait of the young woman today is a still life of sorts, asking whoever picks it up to examine characters ostensibly failing at life and see those failures reflected back at her. Am I a cliché of my own ambitions and naiveté? it asks of its reader. Is there a way to transcend the mold I’ve been put into, first as a girl, and now maybe as an almost-woman?

In recent years, contemporary fiction has seen a tremendous rise of the so-called “girl book”—novels that not only have the diminutive word in their titles, but that question the very meaning of modern femininity in this way largely through disturbed and troubled main characters, characters who fall on a spectrum of psychotic from murderous (Gone Girl, Girl on the Train) to cultish (The Girls). What sets The Babysitter at Rest apart from these is its more nuanced and subtle distortion through which the women are portrayed. They are familiar, selves we may have been once in the past or could see ourselves being in the future: a grown woman who literally needs a manual to figure out how to be a functioning adult; a too-old babysitter whose affair with her employer renders her more of the charge than the baby she’s ostensibly watching; another woman trying to have a baby; one dying in a hospital; and one barely making ends meet in a pathetic day job. George shifts their circumstances so that, as if enhanced by an Instagram filter, none of them is quite like we have actually seen or experienced: there’s of course no manual to life (though we sometimes want one); the baby being babysat will never age, placing its sitter’s temporary youth and attractiveness in sharp relief; and the medical wards depicted are hubs of futuristic torture. There’s a sense of slight relief when we see the sadism of some of the sexual encounters, for pleasure or for procreation, or what it’s like starting a “career” at a warehouse: I’m not quite there, I’m not that bad.

And yet, George is able to slyly probe the reader’s own sense of what being “there” means through her unfiltered prose. The questions we don’t ask, and things we don’t acknowledge in life, are presented here with unremitting honesty, laughable because they’re off-kilter and because they’re not:

I’ve always been afraid of not getting what I want … I’ve always wanted to be all things to all people … If I am honest with myself, there was always a limit to my potential … If I am honest with myself, I don’t know what I did with all or any of my days. If I am honest with myself, it is a relief. Angel food cake is my favorite food. Nothing was as good as I’d wanted it to be.

These thoughts, from the vignette “Take Care of Me Forever,” epitomize the book’s main concerns about how women routinely, through cultural indoctrination or expectation, fail to truly understand themselves until, like the woman lying on her deathbed in this story, they face a moment of crisis. What form that crisis takes is to be determined, but it’s an unwavering fact in these pages that the crisis is here and now—one that has very serious echoes in reality.

As a writer in today’s world of ceaseless self-promotion, Jen George herself remains something of an enigma. This is her debut novel, and her work has appeared sparingly in online magazines. Taking this mystery into account, The Babysitter at Rest feels even more urgently wise; it’s a writer’s message to readers that by removing ourselves from the melee of twenty-first-century life, we can see it more accurately. And once we achieve that separation, it can be all the more enlightening, and enjoyable, to view ourselves in a funhouse-style reflection, full of the unsightly bulges and scars that make us human.

Published on February 28, 2017