Lovebug

by Brandon Haffner

I’d been huffing model airplane glue for two years before I met Beef Gilbert, but he was the first person to make me feel stupid for it. The few friends I had couldn’t be counted on to look out for me; they could hardly look out for themselves. Those poor teachers at Woodland Acres Middle had bigger messes to clean up. And Mama—she was clueless. Too busy watching Golden Girls or The Price is Right or The Twilight Zone—didn’t matter what it was as long as it buzzed bright on that box of hers—and I couldn’t blame her, because Pops died in a freak accident when I was six, so she was all alone with me. This was another thing drew me and Beef together. His pops was dead, too.

By all accounts, Beef Gilbert was a maniac. He showed up at our school in August of 1987 and soon became known as “the kid who cut that cow open.” Like, if you were to see him for the first time, from afar, you might nudge the person next to you and ask: “Hey—is that the kid who cut that cow open?” Hence the name: Beef.

Around school he roamed the halls alone. Ate lunch by himself at one of those corner tables by the stage where the lighting wasn’t very good. He liked to remind people, loudly and half-grinning, that his mom worked at Wal-Mart and that he lived in a trailer park south of Jacinto City. Word spread that you could get him to do almost anything if you paid him enough.

I was on my second detention when I met him. Early September, the last breaths of stinky, sweltering Texas summer pouring in through broken window seals and cracked concrete. The air conditioning couldn’t keep up. During every lesson—x and y and z axes, power paragraphs, Ulysses S. Grant—we were melting.

I was fourteen and the only girl in detention that day. He was fifteen—he’d been held back a year at his old Houston school—tall for his age, slick blond hair, sweaty, and fat. His breath was a gargling wheeze. His too-big Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles t-shirt sagged off him. His square, thick-rimmed glasses were the kind you’d find on a ninety-year-old man.

He sat surrounded by empty seats. The other kids huddled in the corners to sleep or draw or read comics. Beef was flipping through a porno mag. No effort to disguise the naked woman on the cover. I glanced at our detention monitor, Mr. Briggs, who was young and nervous, and my guess was, being a fresh fish, he didn’t want to bother with this notorious big boy.

If you asked me back then why I, a somewhat self-respecting girl standing on a fragile reputation built from hard-edged coolness and occasional witty jabs, sat next to Beef Gilbert that day, I would have shrugged and said I was bored out of my skull. Which wouldn’t have been a lie—I thought, as eighth graders do, I’d seen the whole world.

“Heard you cut up a cow or something, over the summer,” I said. “Why’d you do it?”

He put down his porno mag and glared at me. He wore dirty gray sweatpants and I saw under the desk he had a little hard-on.

“Me and that cow had a political disagreement,” he said.

I laughed. Then he laughed.

“Poor cow,” I said, joking now. “Was it still alive when you did it?”

“Check this out,” he said. He flipped the magazine around so I could see. On the page was a naked Asian woman on her hands and knees.

“I see the appeal,” I said.

“I doubt it,” he said. “They even got smut where you’re from?”

“Where I’m from? I live four blocks from City Hall,” I said. “I’m not some rich girl.” I thought about my bedroom the size of a janitor’s closet. Mama’s rusty Cavalier I could hear coming three blocks away. Frozen corn dogs, frozen fish sticks, canned noodle soup—our dinner rotation. Bedroom air conditioner that rattled and hummed all night.

But secretly I was flattered. All any fourteen-year-old girl stuck wearing off-brand clothes and cheap hand-me-down jewelry can hope for is that her sweet style and perfect makeup fool someone into thinking she doesn’t live in a run-down duplex.

Flatly, quickly, as if he’d said it before, he said: “Yeah, you’re not rich, and I’m not a lard-ass.”

I don’t know what it was like at other schools, but at Woodland Acres, teachers used detention on kids the same way I use duct tape to fix broken stuff around my apartment. Skipped a class? Detention. Late to school? Detention. Broke into a locker, tore down a poster, stole a kid’s pack of gum? Detention. Made fun of or disagreed with a teacher? Hit a girl, kissed a boy, spit a spitball, made a paper airplane out of a math test? Brought booze or weed or the wrong kind of glue to school? Didn’t stand up during the Pledge of Allegiance? Detention. Hell, if your parents called enough times to whine about your grades, you could go to detention for getting a D. Which meant some kids, God bless them, got detention just for being dumb.

With Beef and all his strangeness waiting for me, detention became something I looked forward to. Like the bell ringing at 3:15 every day, I could count on him being in that room when I got there. Same porno mag, same circle of empty chairs around him, the other kids keeping clear of his body odor.

“What’re you in for?” we started to ask each other, like new cellmates.

And he’d tell me the story, usually something like, “I threw my apple core at Miss Gracie. Ryan Bishop gave me fifty cents to do it.”

And when he asked what I was in for, I’d say, “Same as always.”

And he’d shake his head and say, “Stuff’ll fry your brain,” followed by, “Check out these titties.”

And I’d say, “You know I see titties every day. In the mirror.”

And he’d peer down at my chest, and when Mr. Briggs wasn’t looking I’d pull my shirt up to my collarbone, just for half a second, to show off how good they looked in my pink bra.

This, more or less, became our routine.

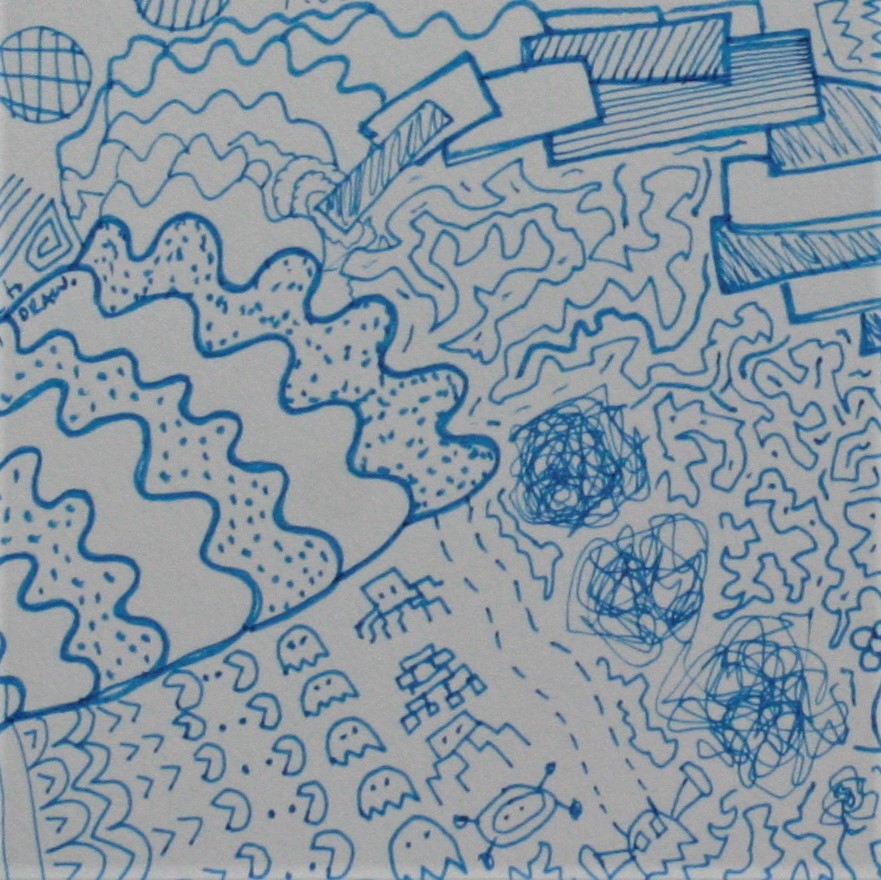

One afternoon in detention, I wrote Beef a note. Mr. Briggs had silenced our conversation with an urgent, pleading glance, and in the silence I stared at my notebook. Usually I would have drawn some crazy thing—a dragon with broken wings, an upside-down truck on fire—but that afternoon I was feeling chatty.

I wrote down some jokes about Mr. Briggs. Scratched some doodles of Mr. Briggs with various classroom objects up his asshole. I added, as a P.S., a suggestion that if Beef were to wear some clothes that fit him, clothes that maybe had been washed recently, he might look better. Not good, not handsome. Just better.

I passed it to him, and he gave me this look: anxious, embarrassed, confused. He seemed more shocked by this piece of paper than by my bra flashes. As he stuffed my neatly folded note into his sweatpants pocket, he coughed and asked, “You going to Ghoulish?”

The Ghoulish Gathering was the Woodland Acres Halloween Dance, the kind of mid-year, low-budget, cafeteria event that attracted only the school’s most desperate and dorky.

“No way in hell,” I said.

“Me neither,” he said.

I continued to write Beef little notes and to receive little notes from him. When he started calling me Lovebug—never in person, only on paper—I returned the affection.

“Dear Lovebug,” we’d start off.

His drawings were faceless stick figures with enormous penises, or terribly drawn motorcycles, or symbols of sports teams. Sometimes he’d draw abstractions, lines and curves and dark spots that had me searching for some deeper meaning. His letters were short and disjointed.

Dear Lovebug, one of them read. I ate like no food this week and am still fat. The universe is unfair. Please stop sniffing glue. It’s gross. One of these days you got to tell me how your dad died.

That was it. No sign off.

About a year before I met Beef, my best friend Mia—who was the type of girl who said “fuck” for no reason and dyed her hair a wacky new color each month and wore rings on all her fingers—walked me over to the gas station one afternoon to buy me my first tube. It felt weird in my hand, hard like a rock, only I could push the sides in a little. Testors brand. “Works the fastest,” Mia said. That same summer she showed me how to stuff tissues into my bra in a way that didn’t look lumpy and I showed her how to cut little slits into the front of her jeans to show off some thigh. “You bad little tease,” I said when she put the jeans back on.

At school I huffed straight from the tube. But at home I used the bag. To get the best high, you squeeze half an inch into the bottom. Place the bag over your mouth and nose. Inhale, exhale. Repeat, repeat, repeat, each breath deeper than the last, and soon you’re riding an escalator up a grassy, flowery hill, above the clouds, and if you’re lucky, it’ll be sunny up there, and if you’re luckier still, you’ll meet Jesus Christ. Boredom was never so beautiful.

Beautiful for about twenty good minutes anyway, and then I’d start finding myself in the bathroom wiping blood from my nose with toilet paper. I started buying tissues at the gas station every time I reloaded my supply.

I started looking for Beef in the halls between classes. One time, I stopped by his locker and asked him about the pictures taped to his door. Mostly cutouts of women in bikinis. A few photos of his Rottweiler.

“His name’s Ass Wipe,” Beef told me.

“Fitting,” I said. “He looks like shit.”

“And this one’s my dead dad.” He pointed to a young-looking, physically fit bald man wearing a collared shirt, clean white dress pants, and shiny dress shoes. He was sitting in a rocking chair, smiling at the camera.

“How’d he die?” I asked.

“Overdose,” Beef said, laughing and wheezing, then coughing. He looked at the photo and pressed his index finger against his dad’s head. “Yeah. He was a dumb bastard.”

And another time by his locker we were playing rock-paper-scissors to see who’d get the last piece of gum in the pack we’d pooled money to buy from Patrick Hutchins last detention. Beef threw paper and I threw rock, so he covered my little fist with his big hand, then said, “I don’t want it,” and handed me the last piece.

“Thanks Beef,” I said, popping the blue stick in my mouth. “What’s your real name anyway?” I asked.

“Dennis,” he said. I’d expected a war to draw it out of him, but he didn’t hesitate. “Dad used to call me Denny.”

“Denny? Like that breakfast place?”

“I told you he was a dumb bastard.”

I was only trying to play along when I said, “Well at least someone’s continuing his legacy.” I even elbowed him in the shoulder and winked big and hard to exaggerate the sarcasm, but I knew as soon as I said it I’d cut some place in him that was dark and bruised.

“Whatever. At least I don’t wear kiddie clothes and a gazillion layers of makeup,” he said, punching his locker shut. “You look like one of those creepy five-year-old pageant girls.”

Normally his lines about my dress weren’t so vicious. More like failed attempts at flattery. This particular year I wore a lot of pink. Pink fingernails, pink T-shirts, pink bobby pins, pink shorts. I even owned a pink watch. I didn’t wear all this at once, of course. Tasteful pink. “Your highlighter shorts are blinding me,” he’d say, or “My little cousin has a Barbie in that same outfit.” He’d gurgle and wheeze and laugh at his own joke and I’d roll my eyes.

But when he crossed the line—“I bet you got a whole dresser full of pretty pink panties,” for instance—I’d make a point, in front of whoever was watching, to demean him.

I’d say, loudly enough for a few bystanders to hear, “Give you two bucks to fall down these stairs,” or “Give you a buck fifty to slap Mr. Briggs on the ass,” or “How about you full-on sprint to each of your classes today, Beef? A quarter per class.”

Sometimes Mia was with us. She would help me find loose change to give him.

“He’s hilarious,” she’d say. “He’s something else.”

He’d do whatever I asked. Every time. Didn’t matter how many people were around to laugh at him, or how much detention it landed him, or how bad his coughing got afterward. He took the money up front. Usually he smiled about it, his dorky sad smile beneath those gigantic glasses. The kid was a walking cartoon character and he knew it. A clown. Almost everyone seemed amused by his act.

Sure, I stood and watched with the rest as he performed. But if anyone had glanced in my direction, they’d have seen how I felt. More than once I caught myself pressing my hands together and shifting my weight from foot to foot, hoping to God the poor idiot didn’t hurt himself.

Now that I think back, it wasn’t nervousness or even guilt. It was much more. It was that sick, stabbing pain in my gut, almost how you feel when your lover betrays you. Disgust. Disbelief. It was that he’d truly do anything. It was that, after a long day of shit grades and nasty looks from teachers and throbbing glue headaches, sometimes all I wanted was detention, his big dorky eyes looking at me and his sweaty notes making me laugh. It was fear that this poor fat boy loved me. It was fear that I could love him.

Tuesday after Labor Day I sat on one of those concrete benches overlooking the school’s brown front lawn, waiting for Mama to pick me up. She was late as always.

I pulled out my notepad and drew gargoyles and princesses. When detention got out, Beef walked through the glass doors and sat next to me.

“You got any pot?” I asked. “I been thinking about trying pot.”

“You know I don’t do any of that shit,” he said. He shook his head for emphasis.

“Just fooling with you,” I said. “Grump.”

We sat. An airplane ripped the sky open. Someone far away pumped some life into a lawnmower.

“When I first heard about you I thought you’d be some tough guy,” I said. “Some brute. A name like Beef. Beef who killed a cow. But I bet you’ve never even seen a cow in your life.”

No response.

“Sorry I missed you today,” I said. “What were you in for this time?”

“Wasn’t my fault. Just some assholes being assholes,” he said. “Like always.”

“You gonna beat them up?”

“Shut up, Emma.”

“I bet you never hurt anything ever.”

“How much?” he asked.

I looked at him.

“How much you want to bet I’ve never hurt a thing? For real,” he said. He was wheezing again.

“You should see a doctor about that chest problem you got,” I said. “Because that shit ain’t normal.”

“How much?” he asked.

“A buck,” I said. “Show me what you got.”

We went behind the school and into the woods, down a long hill on a foot-worn pathway, over a wooden bridge, and across a creek littered with beer cans and cigarette butts and candy wrappers. I’d never been back here before. After twenty minutes, the woods opened up into a green-yellow pasture, a few sun rays spotlighting the place, including, in the distance, an old blue farm house and its grey barn, and, just beyond the barn, the highway coming into the city.

Beef grabbed hold of the low wooden fence in front of us. Just a few feet away, like a joke, was a “No Trespassing” sign, accompanied by a bigger, handwritten sign that read, “I Will Shoot You.”

“Seems taller than it was before,” Beef said, running his hand along the fence. He lifted a heavy pale leg over the wood, made a grunting noise, and landed clumsily on the other side.

Then I climbed over. He watched me.

“Even I’ve got more grace than you,” he said.

I punched his arm. He pretended it hurt.

I followed him away from the house and down near an algae-covered pond. Mosquitoes swarmed.

“Here it is,” he said, pointing down at our feet.

It was so much a part of the earth it was hardly noticeable. But yes, indeed, there was a dead cow, or a pile of dried-up cow parts I should say, in fact not recognizable as a cow at all, except that I knew what I was looking for. There were no flies because the flesh was gone. Just a few bones, dead grass, and a big dark-colored spot on the ground.

“Tell me the truth, Beef,” I said. “You did this?”

“Fuck yeah, I did,” he said. “I’m a murderous cow-killing machine.”

“A true psychopath,” I said.

“A raging psychopath,” he corrected.

“Twenty bucks says you found this cow dead of natural causes.”

He kicked the small pile of fragile bones. Dirt and bone fragments everywhere. The mosquitoes were giving us both hell, and he swatted at them crazily, like each bite was a surprise.

“I like this dance you’re rocking,” I said.

Then he grabbed my wrist hard and he pulled me away from the bones. He led me back to the fence. My wrist started to hurt and my fingers were going numb, so I yanked my arm away.

“What’s your problem?” I asked.

“You don’t have to insult me every second, you know,” he said.

We walked through the woods without talking. The crunching leaves. His labored breathing.

When we got back, Mama’s brown station wagon was waiting for me.

“Want Mama to give you a ride home?” I asked him.

But he ignored me. He sat on the bench, took his glasses off, and set his chin in his hands as we drove away and left him there to wait for whoever.

I spent a lot of time in my room that year. I listened to Blondie and The Clash. I drew two-headed unicorns and tornadoes uprooting neighborhoods and man-eating plants. I threw darts at an old dartboard I’d found in a Pizza Hut trash bin when Mia and me were wandering around town one night looking for stuff to do.

And I talked to Beef on the phone. He was sometimes funny, sometimes stupid, sometimes sweet. But always surprising.

I’d ask, “What are you doing right now?”

And he’d say, “Taking a dump,” or “Training for the Olympics,” or “Waiting for you to come over one of these days so I don’t have to play checkers by myself anymore.”

And I’d make suggestions for the future, like the time I said, “Once you get your license we should go to the Cinemark. You like horror movies?”

“Nah,” he said. “My life’s a horror movie.”

I laughed. One morning later that week, though, I got the sense of what he meant. I found a note in my locker he must have slipped through the little vent:

Dear Lovebug,

Chase who is my asshole step-brother and me and my cousins went to that pond last summer and they gave me a knife and said stab that cow. They didn’t pay me so I said no way. But they got this syringe and stuck me with it. They pushed me down so I wouldn’t get away. They are doing all sorts of drugs all the time with my stepdad so I might have gotten some drugs in me. They said stab that cow or we’ll keep on sticking you. I didn’t do it on purpose.

It could have been my imagination, but that note changed us. I mean, we never spoke about it. I made sure of that. In fact I made sure the word “cow” didn’t even come up in conversation. But this secret, twisted story had an effect. We joked less. Maybe we were nicer to each other. At least until those miserable weeks after Ghoulish.

One late night on the phone, after Mama’d gone to bed, I told Beef how Pops died in a factory fire, and that I hardly had any memory of him, just a flash here or there from some tiny corner of my brain, his image fading more each year.

Beef asked, “Was your dad nice to your mom?”

I was on my knees on my bedroom floor and prepping a huffing bag. I brought the bag to my face and breathed in, breathed out, in, out, in, out.

“Are you doing what I think you’re doing?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Don’t remember what you’re doing?”

“If Pops was nice to Mama. Too young I guess.”

Sometimes our conversations went so deep into the night we’d start to nod off, phones pressed to our ears. One of those nights, I was in bed with my eyes closed and the lights off. A long stretch of silence went by. Beef was breathing slowly, loudly.

“You awake?” I asked.

“No,” he said.

“Me neither.” I said.

The rumbling air conditioner switched off. The crickets in the yard hissed and pulsed. A streetlamp buzzed.

“Why don’t you like your mom?” he asked. “I want to meet her. Decide for myself.”

“She’s lazy. Sits around the house all day. Gets her welfare check and goes straight to happy hour. And she hates me,” I said. “She hates everything. She’ll hate you too.”

“Well your taste in music is pretty terrible. And your drawings. If I were your mom I’d be disturbed by those drawings.”

“I don’t even think she knows I draw.”

“I’d send you to an institution.”

“Wouldn’t surprise me if she did. Get me out of the house.”

“You should show her. Draw something not so gross. I’m being serious. You know, guilt her into putting it on the fridge and shit.”

“It’s a little late for the fridge. I’m not six years old.”

My ear was getting hot, so I switched the phone to the other side.

“She a druggie?” he asked.

I almost laughed. “Mama’s not cool enough to do drugs.”

A long silence.

“Did your pops?”

“Did Pops what?”

“Do drugs,” he said. “You know. Crack. Pills. Meth. Weed. Glue.”

“He drank a little,” I said. “I don’t know.”

I tried to picture Pops. Maybe it wasn’t my memory—maybe it was Mama’s complaining for years after he died that created the picture—but with my eyes closed, my brain all afloat on glue air, I could see Pops with a glass of brown liquor on ice, sitting on the orange couch in the living room, watching M*A*S*H. That couch was the one our old cat, Juniper, used to piss on, the one Mama and me took sledgehammers to a few years ago. Juniper—I’d almost forgotten about him. Raggedy gray hairball, always hissing at everybody but Mama. If you wanted to find him, you’d just look under that couch—two narrow yellow eyes and a low growl would be there to greet you. Mama loved that cat. Saw herself in him a little bit, I think. Not long after we tossed out the couch pieces, I came home from school to find Mama crying on the floor holding a limp, lifeless Juniper. I can’t say I was too upset about that cat’s passing, but for Mama it was almost like Pops had died all over again.

“Emma?” Beef said. I realized he’d said it several times. I was almost asleep.

“Oh,” I said.

“Goodnight.”

Two weeks before Ghoulish, a tall boy from my lunch table asked me to go with him and I said yes. In detention one afternoon I shamelessly told Beef all about him, hoping, I think, to see the hurt on his face. The boy’s name was Alfredo, he was from San Antonio, and he said corny shit like, “You’ve got a great Emma-gination,” his eyes were starry green, and his hands were that perfect blend of soft but firm on my hip in the lingering moment after a goodbye hug in the hall when he didn’t want to let go just yet.

“Sounds like an asshole,” was all Beef could muster.

But a week later Alfredo either forgot about me or changed his mind because he asked out none other than my Mia, and when I told Beef, he said, “Your Mia? Mia Mullins?” and I said, “That’s the one,” and Beef said, “What’s he thinking? She’s got more acne than you and me combined.”

As we parted ways, surprised to find my hand shaking a little, I handed him a note, which went something like this:

Dear Lovebug,

Have a hot date yet for Ghoulish? If not, want to go with? Don’t get ideas.

He handed me his response in detention that afternoon:

Dear Lovebug,

Hope you break dance cause I’m a champ.

That week on the phone, all he wanted to talk about was the dance. He said things like, “I’m going to bring a bag of sugar in case they play ‘Pour Some Sugar on Me,’” and “I bet you’ve slow danced with like a hundred guys.”

“I want to cut out like halfway through,” I said. And I told him I’d pictured the two of us talking in a corner, not dancing at all, maybe heading back to my room to listen to music and draw and talk, like Mia and me used to do.

“Your mama won’t mind?”

“Have you been listening to anything I’ve ever told you? Mama doesn’t mind anything.”

“Okay, but we gotta slow dance once,” he said.

“No promises.”

“Number one hundred and one, here I come.”

But of course we didn’t get that far.

Mama left me $20 a week. Every Monday morning there was one bill on the kitchen counter. Given that Mama had no job, I always wondered where this money came from. I found out later it came out of Pop’s life insurance. The poor man was funding my glue habit from the grave.

Back in 1987 you could buy a lot with $20. Four or five movie tickets. A new shirt. A Sony Discman. A decent dinner out. A shitload of ice cream.

Or a dozen eight-ounce tubes of Testors.

But the day before Ghoulish, when it came time to resupply, I found the Walgreens completely out. So instead I picked up some paint thinner—I thought I’d heard about one of Mia’s friends using it. Came in a plastic bottle a little taller and narrower than a soda can. I walked home and ran up to my room and stuffed the bottle under my mattress.

Then I went downstairs for dinner; I remember this dinner well. For some reason Mama’d cooked lemon pepper chicken and some type of stuffed pasta with actual dinnerware, not the plastic plates I usually took up to my room. It was the most impressive meal I’d eaten in months. Before sitting down, I asked:

“What’s the special occasion?”

I got this nasty look from her and some response like:

“Does it need to be a special occasion if I want to cook some damn chicken for us?”

“What’s up your ass?”

“If you’re gonna talk like that don’t talk at all.”

“Fine with me.”

We ate the delicious meal in dead silence, save for the smacking of our lips and the clinking of our forks against our plates. When I finished, I went upstairs, locked the door, cranked “Death or Glory,” stuck my hand under my mattress, pulled out the now-warm can, shook it, heard my liquid destiny sloshing around, and took, as they say, the plunge.

Dear Lovebug,

When I wake up to get ready for school in the morning and put my clothes on, I sometimes pretend my clothes are ancient armor. Many, many girls for hundreds or thousands of years have worn this same armor and now it’s mine. It’s all rusty and it’s got some holes because you know it’s so old, but for the most part it’s good trustworthy armor. Now that I write it down this seems dumb. But even though it’s pretend and I know I’m too old to pretend, the armor has got me through lots of mornings when I just didn’t want to go to school. You know what I mean? Do you know what I’m talking about?

Anyway I’m writing this note at the hospital so I won’t be at the Ghoulish and you’re probably not going to get this note in time but I thought I should write it anyway.

Yes, I’m in the hospital for the reason you’re thinking.

I guess that’s all.

Emma

At the bottom of that note was a drawing of my own face, frowning, a tear streaming down one cheek. The finished product—eyes way too big and wide, too many half-erased sketch lines around the edges, crazy hair, pointy nose—looked nothing like me.

As any idiot could tell you, huffing paint thinner isn’t anything like huffing Testors. Less like riding an escalator up through clouds than like riding a train that’s on fire and the cabins are full of smoke and the whole thing is sailing off the tracks down into a ravine and you know it’s just a matter of time before you hit bottom and blow up into smithereens, but until then your stomach is flipping and churning and you feel weightless and terrified at the same time as the whole world rushes past you at terminal velocity or whatever.

The instant I unscrewed the cap, my face a good foot from the bottle, the fumes filled my room. The smell swept me back to those lighter-fluid-drenched junk heaps in the woods. I closed my eyes and took a few deep breaths. I stuck my nose into the opening and took a huge sniff, followed immediately by another huge sniff, figuring I could skip a step—the bottle acted like a bag by way of concentrating and trapping those wonderful toxic fumes.

Who knows why we do these things to ourselves?

Imagine using two mortars to mash up some glass and habanero peppers, then jamming those glass-and-habanero-caked mortars up your nostrils. Even after I yanked my face from the bottle, grabbed a tissue, and began blowing, and even after those bloody chunks started falling out of my nose more thickly and rapidly than the tissues could contain—my khaki shorts and pink carpet were soaked with red by the time I passed out—the inside of my nose burned so bad I was crying.

If my life was a movie, I’d have woken up in the hospital bed. Peaceful and rested, surrounded by “get well” balloons and some doctor giving me a solemn but hopeful look. No such luck for 14-year-old Emma. No, I woke up in the ambulance, where the pain in my nose was still intense and burning. No way my nose survives this, I was thinking. It’s gonna have to be surgically removed. I’m gonna be noseless forever and they’re gonna make fun of me worse than they make fun of Beef.

Added to my nose pain was this unbearable headache, as if I’d banged my head on the ambulance door as they stuffed me in. I couldn’t stop coughing. My heart raged against my chest like a deranged gorilla. I was surrounded by fast-talking, stressed out, overworked strangers.

Other things I remember: Real bumpy ride. Blurry vision. Lights hurt my eyes. Cold as a freezer. Why was the air conditioning up so high in there? Where was Mama? Wet blood slowly drying on my face. Tried to open my mouth to ask for a Tylenol or something, but nothing came out but another painful cough. And no eye contact with the strangers. Not the whole way to the hospital. What I can’t tell you is if I was avoiding their eyes or they were avoiding mine.

After they got me all fixed up with tubes and oxygen, Mama walked in the room. There was no window, and everything was beige. She sat in the chair next to my bed.

Mama folded her hands in her lap and said, “Emma.” She’d been crying. It was obvious. Puffy red cheeks, wet eyes, that permanent frown of hers. Her half-gray,-half-black hair was a mess.

She put her hand on my hand. I was too weak to move it away.

I expected Mama to get up and leave after an hour or so. But I fell asleep, and when I woke up it was morning, and she was still there, asleep in the chair, her head leaning awkwardly on the beige wall. Later on it would dawn on me that this was the longest stretch of time we’d been in the same room together since Pops was alive.

Mama went and got me breakfast from the hospital cafeteria and came back and we ate together in silence.

“Are you depressed?” Mama said when we finished. When our eyes met I realized she’d been spending most of breakfast working up the courage to ask.

“No, Mama.”

“Did some boy hurt you?”

I laughed, then coughed.

“Well then what?” she asked, impatient. “What is it? People don’t do this for no reason.”

“Sure they do,” I said.

The nurse came in, drew my blood, and left.

“She seems nice,” Mama said.

“I don’t like her,” I said, which was a lie.

Mama stayed with me for the next day and a half.

“It’s no trouble,” she kept saying, as if I’d told her she was outdoing herself. “I’ve got nowhere to go.”

They rolled in a TV and we watched whatever Mama wanted to watch. I went in and out of sleep. The doctor told me I was a “perfectly healthy young woman,” but that I wouldn’t be this way much longer if I kept “poisoning my body,” and “brain damage” and “heart damage” and “sudden death” and this and that, and he handed me a pamphlet with the words “FREEDOM FROM ADDICTION” written at the top in all caps, which I threw in the garbage outside the hospital, and which Mama fished out of the garbage and clutched in her lap with her non-steering hand during the drive home and then studied at the kitchen table through her reading glasses for like a gazillion billion hours.

I must have called Beef fifteen times that weekend. On Sunday night, his mama answered the phone. She told me Beef—she called him Dennis—was resting up and wouldn’t be at school for a bit. Then Ass Wipe started barking and she said she had to go.

Mia told me the story at lunch that Monday. Turns out Alfredo had showed up to Ghoulish drunk. Slurring his words, not walking straight. Beef was there searching the crowd for me in his I’m-sure-ridiculous-looking Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle costume. He found Mia and asked her where I was, and Alfredo, who was standing right there, asked Beef how he could be so stupid as to think I’d actually dance with him. Acted like I’d set the whole thing up as a gag. So Beef plopped down at one of the tables behind the crowd and just sat there like a lonely egg. But when Mia went to the bathroom, Alfredo tracked Beef down, acted all remorseful, told Beef I wasn’t worth getting all depressed over, that I wasn’t even that good a kisser—which is a lie—then offered Beef fifty bucks to sneak behind the cafeteria stage curtain, climb the spiral staircase to the catwalk above the stage, and jump off while hollering, “Cowabunga dude!”

So he did.

The stage exploded as if Beef were a human bomb. Broke his left leg and nearly his hip. But the worst part: this little shard of wood came up and stuck Beef right in the eye. Blood was everywhere. As Mia put it, “Everyone was running around screaming like it was the end of days.”

Monday of next week I finally saw him during my break between Spanish II and study hall. He walked toward me down the hallway on crutches, a black eye patch over his left eye. If I hadn’t heard the story first, I would have figured somebody was paying him a buck or two to act like a disabled pirate. When he came close enough to hear me, I took a risk and made a joke of it. I said, “Ahoy there!” But he didn’t respond. Didn’t even crack a tiny grin. Instead, from his right eye, he shot me this wild glare, kind of like the glare a horse—or a cow—gives you when you walk too close to the fence. Like they’re scared and pissed at the same time.

Then Beef lifted the patch to reveal a mess of purple and black flesh.

“Give me a dollar,” he said, “and I’ll let you touch it.”

I stood there like a dope.

“People been handing me money all day to put their fingers in my eye socket,” he said. He reset the patch. “Some people are so disgusting. Wouldn’t you say, Lovebug?”

I didn’t agree or disagree. I dug around in my rotten brain but the words were buried too deep. And after a few awful seconds, he limped off into the crowd.

At home that evening, in my bedroom, my paint thinner was nowhere to be found. My bed was made, too. And the next Monday morning, there was no $20 bill on the kitchen counter.

Weeks went by. I wound up in detention less and less often. The sweltering summer heat was replaced by breezy windbreaker weather. Beef and I still talked sometimes, in the halls. Not like before, but little stuff, like, “Does Mr. Briggs still pretend those ladies in your magazine aren’t naked?” and “Your mama got a new boyfriend yet?” Stuff like that. Then one day he told me he was moving to Louisiana over winter break to go live with his grandpa. Set to go to some high school in Baton Rouge. He’d already been out to visit.

“Best part is, everyone’s a lard-ass out there,” he said. “Even lard-assier than me. For real. I’m gonna be the hot jock.”

“The Hot Jock Cyclops of Baton Rouge.”

“Don’t push your luck.”

His mama’d had a heart attack or something, he said. Hence the move.

Christmas Eve. In my bedroom. Beef had been gone a week. “Train in Vain” blasting on my stereo. I was wrapping a present, believe it or not, for Mama. A pencil drawing of nothing special. A river, flowing down a canyon, and in the middle of it, this big zig-zaggy tree emerging from the water, branches reaching up toward the sky. It was pretty bad even by my standards—never was much of a nature drawer. Figured I might as well give it away. Plus once I’d finished and stepped back from it, that crazy tree kind of reminded me of her. Weather-beaten and old and strange. The type of tree all the tourists would come to see and snap pictures of while asking impossible-to-answer questions like, “How the hell did it get in the middle of the river in the first place?” and “Why hasn’t it fallen down after all these years?”

When she opened it on Christmas morning she cried so many tears it was like God had opened a bottle of champagne all over our living room. She gave me a hug—our first hug in I don’t know how long—and thanked me over and over. It was a little excessive.

After presents, we sat on the couch. She held my hand while her terrible Christmas music played in the background and we sipped the lukewarm hot chocolate she’d made. As she stared out the living room window—where there was nothing but cold, frosted lawn and a deserted street—she had this odd little smile. Her face was still wet. After a few minutes I cleared my throat, and she stood up and asked if I’d like her to reheat the rest of the hot chocolate. From her eyes I understood she wanted me to say yes.

I thought of a thousand smart responses. “Sure, nothing more delicious than chocolate water garnished with powder clumps,” or “But wouldn’t reheating mean it was once heated?” But when I practiced them in my head, none of my one-liners was the clever little needle I wanted. On this quiet Christmas morning, everything I thought to say was a jackhammer, a chainsaw, a blowtorch. So I gave it up.

Inhale, exhale. Repeat, repeat, repeat.

“Sure, Mama,” I said, handing her my empty pink mug.

Published on May 9, 2019