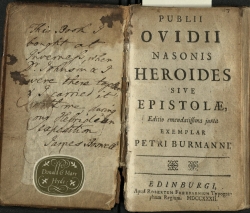

Ovid’s Heroides

by J. Kates

One of the least remarked and most remarkable qualities of Ovid’s writing is the attention he paid to women. As Philip Freeman has written in an introduction to the Greek poet Sappho,

Almost everything written in ancient times, from Homer to Saint Augustine, was composed by men. Even on those occasions when men bothered to write about women, the words come to us from a male point of view, full of ignorance and prejudice. [1]

There were women writing in their own personae in the Greco-Roman cultural world. But, as far as I know, Ovid is the very first male writer (outside the theater and some girls’ choruses by the Spartan poet Alcman) to write in a woman’s voice.

Nowadays, we take this kind of thing for granted, but in the Roman society of his day it must have demanded an immense leap of the imagination. The collection of poems known to us as the Heroides, “the women of the heroes,” is just such a leap. Ovid recreated missives from eighteen heroic women of his mythology along with correspondence from three of their men. Some of the women are still, like Medea, Penelope of Ithaca, and Dido of Carthage, quite well known. Others have faded into mythic obscurity. One, Sappho, has an established historical existence. Each of the invented letters rings changes on the same theme: love, one the Middle Ages knew Ovid had patented. Looked at in one way, these are all elaborate exercises in rhetoric; looked at in another, they are all torch songs.

The book opens with Penelope pining for Ulysses, as we shall call Odysseus in these pages dedicated to Latin literature. She has imaginatively followed the warrior exploits we know from The Iliad, but some time after the sack of Troy he has gone missing in action. She fears—res est solliciti plena timoris amor, “love is a matter filled with anxiety”—for his own safety first, for herself and those who urge her to abandon her absent husband, for Telemachus, their son, and finally for the ravaging of time: Certe ego, quae fueram te discedente puella, / protimus ut venias, facta videbor anus, “It’s a sure thing that I, a girl when you went away / however quickly you come, will look like an old woman.” There is nothing particularly deep in Penelope’s concerns by modern consciousness, what is revolutionary is her voicing them at all.

Quite recently, the poet Tino Villanueva has come out with his own invention of what was going on in Penelope’s mind as she waited for Ulysses. [2] The poems of So Spoke Penelope are mostly introspective midrashim. Midrash is a literary genre the name of which derives from Talmudic studies, but there’s nothing particularly Jewish about the practice. It consists of taking an established canonical text and inserting narrative or psychological amplifications where they do not already exist. Midrashim serve as a form of commentary, but they are also a mechanism of expansion. From the days of the Greek dramatists, the Homeric epics have served as sources for variations on narrative and theme. There are some who argue that these theatrical and lyrical variations actually constitute a kind of translation in and of themselves. I would not go that far—but I would see them as a kind of midrash.

Only in Villanueva’s “Possessed By Doubt” and “Come to Me” does the patient wife directly address the absent man of her dreams. Here is how his Penelope begins:

Come to me

as a far-away star would reach me, Odysseus,

husband whose love alone allays me.

And here is how Ovid’s long-suffering Penelope opens her letter:

Hæc tua Penelope lento tibi mittit, Ulixe;

nil mihi rescribas attinet: ipse veni!

which could be fairly literally rendered:

This [letter] Penelope sends to you, loitering Ulysses;

nothing you may write to me matters: come in person!

However unconsciously (the poet has said he was unaware of Ovid’s work when he wrote his own), Villanueva caught the echo of this longing. But the Latin lines work not only as an appeal to one tardy husband. They also serve as a prologue and a kind of counterweight to the entire collection of letters that follows. “Don’t write—come to me” slyly counterweighs every bit of writing to come. There is an added joke in the adjective, lento, of the first line: in addition to “slow, lingering,” lentus can also mean “inactive, apathetic, phlegmatic”—all of these in obvious contrast to the epithet for the same legendary guy in the first line of the Odyssey, πολύτροπον [3], which implies, at least, some kind of movement.

And now, Clare Pollard, an English poet, has given us her own readings of the first fifteen of the Heroides in Ovid’s Heroines. [4] She has claimed, as Villanueva did not, to be a translator. She has chosen to emulate, as she explains in her stellar introduction, Ted Hughes’s renderings of selections from the Metamorphoses, “allowing me to explore … the pacing, the hypnotic repetitions, the tragi-comic shifts, the immediacy of the voices.” Alas, I wish she had played by her own rules.

For her, spacing does much of the work of rhetoric, and the Latin internal rhymes (“Penelope lento”), bumping against the long vowels and stumbling t’s of the original, get distilled into a single line of r’s and m’s. By “immediacy” she clearly means minimalism.

Dear Ulysses,

you’re late.

don’t worry about answering, just come home.

I don’t know about you, but if I had received that little snippet of postal hectoring, I’d settle right down with divine Calypso for another seven years.

Ted Hughes is certainly partly responsible for the style, and so is Robert Lowell, who tried so hard to eat his cake and have it too [5], as well as a misreading of Ezra Pound, in abdicating responsibility for any of the form or vocabulary of the source-text, as if nothing mattered but the barest bones of sense. For a contrast in translating styles, here is David Slavitt [6]:

These words, dear slow Ulysses, Penelope dispatches;

never mind the favor of your reply,

but come, yourself, at once …

continuing the sentence that Ovid has broken off with his own urgent Ipse veni for another three and a half lines. You hear an entirely different rhythm here, the measured cadence of the elegiac meter. Slavitt stands at the opposite pole from Pollard.

We can call Pollard’s approach one of connect-the-dots. She picks out particular points and leaps from one to another, a sketchy kind of drawing. Although the 116 elegiac lines Ovid devotes to Penelope count out to 102 in Pollard’s version, many of hers are of the ilk, “I was a nervous mess,” “Where are you?” and “you’re male, after all.” These are not mistranslations, they are simply inadequate. Slavitt’s technique is more like Crayola coloring, filling in the given outlines with inventive shading.

The second most famous letter-writer in Ovid’s gallery is Dido, the tragic victim of Rome’s own epic history and the seventh correspondent of the Heroides. Dido writes not because her man hasn’t arrived, but because he’s on the point of leaving. Her letter to Aeneas is a 200-line suicide note, and she ends it with her own epitaph. But she introduces it quite literally as a swan-song:

Sic ubi fata vocant, udis abiectus in herbis

ad vada Maeandri concinit albus olor. [7]

These lines, invoking the fates, echo the opening of the Aeneid, where the hero is fato profugus, forced on by fate, where the poet begins also by singing, and where the Meander River runs through Trojan territory. If we note that the verb concinit implies not just singing, but singing in chorus, or singing at least in some kind of echoing or communal context, the expression expands immeasurably. But for Pollard,

The white swan sings, sinks

into sodden grasses.

I know it’s impossible to get it all (see “Getting Horace Across”), but I can’t help wishing she had tried for at least some of it. A. S. Kline’s “At fate’s call, the white swan, despondent on the grass / sings like this to the waters of Maeander” maintains the referents, as does Vaughan’s “As, when fates call, cast down among damp plants, / the white swan sings on the streams of the Maeander.” Both of these, I think, err on the side of oleaginity, but at least it’s with flavorful oil and a smooth movement. [8]

Even as I write all this, I want to like Pollard’s Ovid. I’m desperate to like it, for all the very good reasons she cites in her introduction and even for the irrelevant additional political notion of wanting a woman’s voice to render the Roman man’s women. But I am not a fan of this kind of reduction, all too common in translations of Greek and Latin literature.

So what is it that Villanueva got right that Pollard gets wrong? It is simply that his Penelope has a real voice, and one not banal in its introspection. Pollard’s version of “res est solliciti plena timoris amor” sounds querulous and diminished: “I mean, I know love makes me anxious.” Villanueva, in “How I Wait,” gives Penelope a whole volume to expound this text.

Today I sit by a window, my spirit

swimming out into the deep-azure-blue of the sea.

I’m a woman waiting, in love with a man,

and in love with the love we had.

I took an oath with myself to wait,

and keep passionately waiting

even after the great shining of the sun has worn away.

This sounds as if it could be a translation of Ovid. It rings with the voice of the Roman’s forlorn Penelope in a way that Pollard’s does not. She is certainly capable of warbling with a rhetorical felicity: “My sick heart surges, blurry / with love and fury.” [9] But for the most part she contents herself with the same old staccato diminution: “I mix this plea with tears. / You are reading my words. Imagine my tears.” [10]

While I’m bitching about Pollard’s omissions, let’s add this big one. Her decision to exclude six letters of theHeroides skews the collection as a whole, not merely by leaving all the men’s contributions out of the text (a defensible if tendentious editing decision) but also by depriving us of one of the most enduring of the voices—that of the hapless heroine Hero as she calls in vain for Leander, already lying dead and soggy on the waves of the Hellespont. Her words toss back and forth like his helpless body in the surf, with the verb “desire” in its two forms (and cognate with the name of the god of love) as particularly poignant flotsam:

Quod cupis, hoc nautæ metuunt, Leandre, natare;

exitus hic fractis puppibus esse solet.

me miseram! cupio non persuadere, quod hortor,

sisque, precor, monitis fortior ipse meis— [11]

These contradictory words launched a thousand lines for Christopher Marlowe, [12] and I, for one, am not content to be deprived of them.

[1] Philip Freeman, Searching for Sappho (W. W. Norton, 2016), p. xxii. Return to Text

[2] Tino Villanueva, So Spoke Penelope (Grolier Poetry Press, 2013). Return to Text

[3] Many-turn: “of twists and turns” (Fagles); ”skilled in all ways of contending” (Fitzgerald); “of many ways” (Lattimore); “of many wiles” (Mandelbaum); and so on. Return to Text

[4] Clare Pollard, Ovid’s Heroines (Bloodaxe Books, 2013). Return to Text

[5] “I have been almost as free as the authors themselves in finding ways to make them ring right for me.” Robert Lowell, Imitations (Noonday, 1965), p. xiii. Return to Text

[6] Love Poems, Letters, and Remedies of Ovid, translated by David Slavitt (Harvard University Press, 2011), p. 137. The title of Slavitt’s book is deceptive. In fact, the poems are not what we usually mean by “love poems,” and the letters are his only by authorship. Return to Text

[7] “Thus where the fates call, thrown down among the wet reeds / into the shallows of the Meander [river] the white swan sings.” Return to Text

[8] “And so, at fate’s call, the white swan lets himself / down in the water-soaked grasses by / the Meander’s shoreline to sing his last song,” Harold Isbell has it, giving the swan a conscious agency not explicit in Ovid, but foreshadowing Dido’s own suicide. Slavitt omits entirely the fateful allusion to the Aeneid: “Thus does the dying swan sing in Meander’s marshes, / the noble white bird in the watery grass.” Return to Text

[9] cor dolet, atque ira mixtus abundat amor (vi:76). Return to Text

[10] Addimus his precibus lacrimas quoque; verba precantis / qui legis, et lacrimas finge videre meas! (iv:175-176). Return to Text

[11] “What you desire, Leander, is what sailors fear: to swim,

the usual escape from shipwreck. Oh, I am miserable!

I desire to convince you not to respond to my own urging:

may you yourself be stronger, I pray, than my warnings —” Return to Text

[12] Actually 818 lines, to be precise, among which the sly allusion to the Heroides, “He being a novice, knew not what she meant, / But stayed, and after her a letter sent, / Which joyful Hero answered in such sort … ” And, of course, “Who ever loved, that loved not at first sight?” Return to Text

Published on June 4, 2018