The Ethics of Memoir: An Author Interviews His Mother

by Robert Anthony Siegel

I had never thought about the ethics of memoir for one very simple reason: I was not a memoirist. For that same reason, I had never thought about the impact a memoir might have on someone included in its pages without her knowledge or permission. Because, you know, et cetera.

And yet all the time I was declining to think about those issues, I was also writing a nonfictional account of certain aspects of my life that included other people, most of whom are family. That this qualified as memoir dawned on me only much later, when my brother sent me a photograph of an open box of books, the author copies sent to me by my publisher, accompanied by a line of text: “Mom took one. Sorry.” Indeed, I could see an ominous gap where a single copy had been removed.

How did this happen? All I can say in my defense is that the honesty involved in the book’s composition felt so radically new to me, and so exceedingly fragile, that I found it necessary to pretend it was not taking place in the real world—that it was, in a sense, just happening in my head, a thing that nobody else would ever see. That people could actually see it left me uncertain.

My mother, Frances, was gracious when we talked about it. “Oh, you are a marvelous writer,” she told me. “The language is exquisite.”

“Really?”

“And the level of insight—excellent.”

In that one moment, the tension left my shoulders and my chest opened to let in air. I had been feeling sneaky and duplicitous, but my mother didn’t see it that way; it was all going to turn out fine. A few weeks later, however, she came to me with a document she’d written, entitled “The Rebuttal.”

“The problem,” she explained, pushing the pages into my hand, “is that you failed to capture the deepest part of me.”

“You don’t think the book is accurate?” I asked.

“No, it’s accurate, but it doesn’t delve deep enough into my life or my motives.”

Hey, wait a second, I thought, instantly defensive. It’s not your book. It’s my book. About me. You’re just a side character—though in the very next second I was shocked and ashamed of those thoughts. And then it struck me: the literary conversation around memoir pretty much always focuses on the writer’s right to speak; there is little or no discussion of what it feels like to be written about—to find oneself essentially fitted out as a character inside someone else’s narrative. Sensing an opportunity, I offered to explore that experience with her in an interview. What follows is our conversation, edited for brevity and sense.

I should also mention that my book, Criminals, focuses on my father, a criminal defense attorney who got tangled up in a police investigation and went to prison when I was in my teens. We tried to hide this terrible turn of events, a choice that became powerfully distorting in its own right as the years passed. Shame, self-censorship, and the question of who owns the narrative and who has the right to speak are thus all germane to the story. But so is literature, that model of uncensored self-expression, a long-standing interest of my mother’s and one of the keys to our relationship.

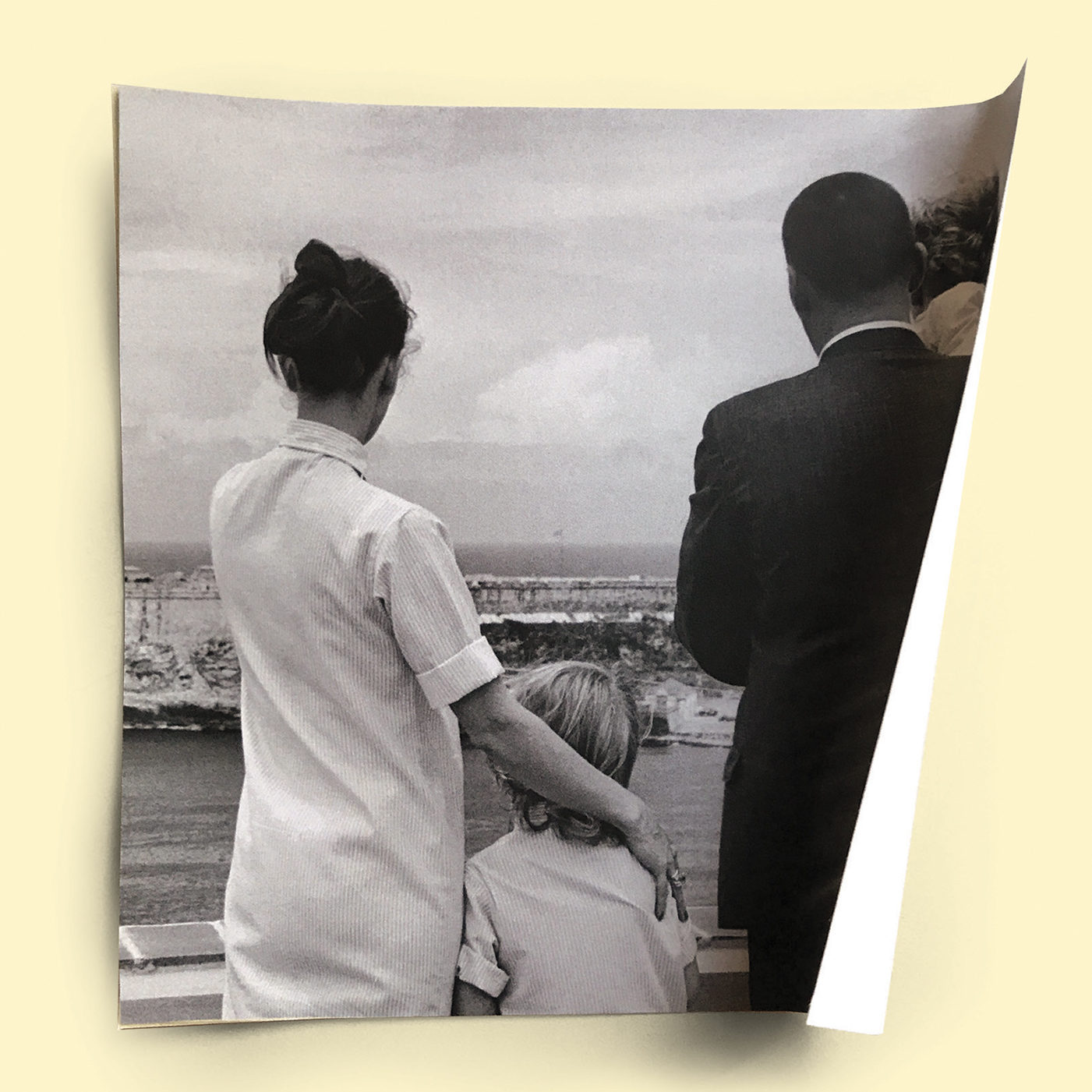

Robert Anthony Siegel: Whenever I see myself in a photograph, I have a moment of disbelief in which I say, That’s not me. I wonder if that’s what it feels like to see yourself in somebody else’s memoir.

Frances Silverglate: Yes, that’s exactly it.

Robert: Do you think it was unfair that I didn’t tell you I was writing about you? Was that sneaky of me?

Frances: No, if you had told me, it might have put the kibosh on it. You have a right to tell your story as you understand it. Still, I have to say that your version of the truth definitely surprised me. I thought you’d had a very pleasant childhood. When I read the book, I was appalled by how anxious and insecure you’d been. It made me sad.

Robert: Do you think it’s wrong for people to write about other people close to them? I don’t want to use the phrase “betrayal of intimacy,” but I worry that I’ve imposed my viewpoint on you and damaged your own.

Frances: “Betrayal of intimacy” isn’t a bad phrase, but no, you certainly have a right to your own viewpoint. It doesn’t erase mine.

Robert: The story the memoir tells is sometimes painful. Do you mind people knowing about it?

Frances: No, I don’t mind. I never felt that I did anything so shameful that I would want to keep it hidden. But I understood that your father felt differently, that he was terribly humiliated and never really recovered from what happened to him, so I honored his wish that I not talk about it. At the same time, I don’t particularly mind anyone knowing, and I don’t feel personally compromised.

Robert: He’s dead now, of course, but do you think he would have been angry at me for writing this book and telling people what happened to him?

Frances: I don’t know. He loved you dearly, and he tended to think that anything you did was superb. So, it’s hard to say.

Robert: One of the themes of the book is shame.

Frances: He was ashamed, terribly ashamed, but I wasn’t. I was just furious at him. His legal troubles changed my life. I had to go back to work after twenty years of not being in the workforce. That turned out to be a very good thing for me, ultimately, but at the time it was the most frightening, difficult experience. Looking back, I’m very proud of myself, but it was a terrible upheaval.

Robert: I think another theme in the book is a certain kind of complicity we all had in the illegality.

Frances: I was complicit. I complained all the time about his cutting corners, but when he came home with a suitcase full of money I was thrilled to death.

Robert: What is it like to read a review of the book and see yourself reflected in a complete stranger’s eyes? Do you find that picture of you unfair?

Frances: Do I mind what people think of me? No, though people have actually been quite kind. But I don’t think that I’m the main story. The main story is your father, and I’m just amazed as I read your account of him. I’ve been thinking about him for the last fifteen years since he died, but I still don’t understand him. So, your revelations have been fascinating to me.

Robert: What did you learn about Dad in the book that was new?

Frances: How complicated he was and how hard it was to understand him—that it wasn’t just me in the dark. To some extent, we were all in the dark.

Robert: You say you aren’t the main story, but that can’t feel good. Did you desire to be more fully seen in the book?

Frances: I felt that you got my motives skewed. Getting out of Brooklyn wasn’t a snobby thing for me. When I was in Brooklyn, I had nobody I could talk with. Dad’s family were lovely people, and they were very kind, but when I came home from holiday to that beautiful apartment on that nice street in Brooklyn, I would get so depressed, you can’t imagine. Whereas in that first ratty apartment we moved to in Manhattan, I never minded getting home. I couldn’t wait to see my friends.

Robert: Does that mean I got it wrong?

Frances: No, the problem was that you were a little boy back then. I simplified too much and you misunderstood me. When I said something like “people in Brooklyn are stupid,” what I really meant was something much more complicated about my life and how I wanted to change it.

Robert: Has your view of our experience as a family changed at all because of the memoir?

Frances: I do think that your father and I should never have married. I never intended to marry him and then, somehow, we were married—and stayed married for forty-three years, till he died. But the truth is that I don’t regret anything, though I am sorry I didn’t tune into your anxieties.

Robert: I’m not accusing—

Frances: That’s it. There is no blame in your book, no whining. It is a forthright tale of what it was like to be a child in one particular family, our family. I’m glad you wrote it. And if you write another one and you castigate me, that’s okay too, because that’s literature.

Robert: Oh, I think literature is for understanding, not blame.

Frances: Well, I do think you caught your father, though I couldn’t help you with that task, because I never knew who the hell he was.

Robert Anthony Siegel’s Criminals: My Family’s Life on Both Sides of the Law was published in 2018 by Counterpoint.

Published on July 12, 2019