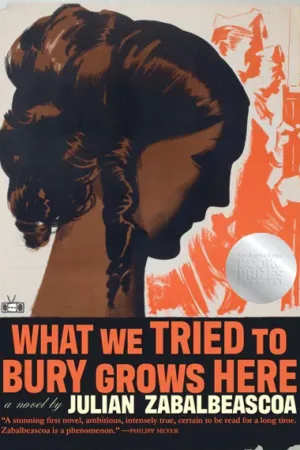

What We Tried to Bury Grows Here

by Julian Zabalbeascoa

reviewed by Scott Schomburg

In Julian Zabalbeascoa’s debut novel, What We Tried to Bury Grows Here, twenty narrators in twenty chapters navigate the Spanish Civil War, when, in 1936, the electoral victory of a left-wing coalition led to Franco’s fascist coup. The novel spans the two years leading up to the victory of Franco’s Nationalist army over Spain’s Republican government. Some of the narrators are fascists; many of them have killed; all of them are witnesses to and/or participants in what Zabalbeascoa has called “the collective suicide” of 1930s Spain, a period in which ordinary people lusted for blood and spoke in “terrible absolutes.” Nationalist soldiers are trained to think they aren’t killing human beings but “a social system,” and even passionate supporters of freedom believe the only choice is war. One narrator, Juana, whose parents left her to join the resistance, receives letters from her mother: “[Your father] and I used to think that nothing mattered more than life,” she writes, “but we were wrong. There are ideas.”

The novel is filled with ideas, such as the narrators’ thoughts about the human costs of so much violence. One soldier, who believes he possesses a light no amount of ugliness can extinguish, still imagines in fleeting moments that “it’s possible to escape the brutality of history.” Another thinks his soul is gone; he can feel its absence. But Zabalbeascoa does not resolve these conflicting visions of the war, nor does he simply place his own divided opinions into his characters. In an essay in Literary Hub, Zabalbeascoa writes about how his creative process became an intentional purging of his own ideas, as he pledged to his narrators that he “would not steer or judge” them, no matter how much blood and loss they would bring. Serving their voices and stories required “curiosity, empathy, and compassion, the very instruments missing from the propagandist’s toolbox.” This deep empathy drives What We Tried to Bury; the author allows his narrators to speak on their own terms, and thus they come alive on the page.

Each narrator’s path overlaps with Isidro, a soldier from the Basque Country resisting Franco’s army. By the time we meet Isidro, he has encountered the writings of Erlea, a pseudonymous political pamphleteer whose galvanizing calls to resist fascism—“monarchists, nationalists, the military, the church, the wealthy”—has inspired Isidro to join the war. His story unfolds from chapter to chapter, a dazzling feat of storytelling that allows us to see the central character from various points of view.

Repeating Erlea’s words—“Spain belongs to its people”—Isidro moves through a devastated landscape as he experiences terrors, including the first carpet bombing of civilians in history, when, in 1937, Hitler and Mussolini sent German and Italian planes to the Basque village of Gernika in support of Franco’s cause. As Nationalists take region after region, Isidro tries to hold on to his ideals: “You’ve heard the fascists, their chants. ‘Viva la Muerte!’” Isidro tells a fellow soldier. “So long as the choice remains ours, we have to choose life.” For Isidro, that means killing Nationalists who stand in the way of a free Spain. For his brother, Xabier, who is a priest, it means believing that every person is worth saving. If that is not true, Xabier says, “we’re lost.”

This conflict is at the core of the novel. If every life is precious, any violence against another person is grotesque. But can one realistically hope, as one narrator does, to both preserve life and end the war? To hold that question without resolving it requires the capacity to exist in uncertainty. But, as another man says, doubt is poison for a soldier. A Nationalist soldier must forget what he knows is true: that the figure in his crosshairs isn’t an ideology, but a human being. In contrast, as a priest, Xabier rejects the paradoxical idea that violence may be used in the service of life. When someone asks him why God would allow so much destruction, he quotes Saint Ignatius: “The Divinity hides itself.” Xabier dedicates himself to that mystery, holding fast to his faith until the very end, when Nationalist soldiers hang him from a tree in a cemetery.

Late in the novel, after Isidro has learned of his brother’s fate, he and Héctor, a Republican soldier, are looking around in the ruins of a Catholic church when bullets hit the pews. Two boys in the Nationalist army, not even fifteen, shoot at them in the church. Isidro fires back, killing one boy and then raising his rifle at the other, who crawls away on his knees. Héctor watches in silent horror. He looks at the empty pulpit and imagines preaching life to Isidro among so much death:

Of course it’s obvious but don’t you see, this fighting has accomplished what the other side was after, it’s divorced us from one another. To hell with survival, with sacrifice, with martyrdom. I have a brother, too, Isidro, and he wasn’t much younger than this boy when the war took me from him. I doubt he’d recognize the person I’ve become. So let’s help this child, perhaps then we might save ourselves.

But Isidro fires another bullet, and the boy is gone. That night, Isidro sits against a tree. Héctor watches him look into the distance, “probably thinking as I often did: sure, I’m still here but have I survived?”

Isidro entered the war with Erlea’s manifestos. By the end of the novel, he has met Mariana, the woman behind the pen name. She shelters him at her home, and they fall in love. In the pamphlet that begins the novel, Mariana writes, “A new Spain is being born, the old dying;” later, Mariana writes to Isidro that she is pregnant. Eventually she gives birth not to an idea but to a life, and Isidro realizes that his reasons for joining the war were not ideological, but relational; he longed for connection. He picked up a gun when he really wanted to be with people. The sliver of hope Zabalbeascoa gives us is not a soldier’s or priest’s, but a novelist’s, whose sacred texts are the human lives in front of him. His faith lies in the novel’s final image of a child rising to her feet, insisting the surrounding women reach out their hands to hers. “One did, then another. She met their eyes and smiled, hers big and untroubled, and grabbed hold of their hands and pulled herself up, shifting her weight, jerking her hips out from side to side, searching for balance, to root herself.”

Published on June 23, 2025