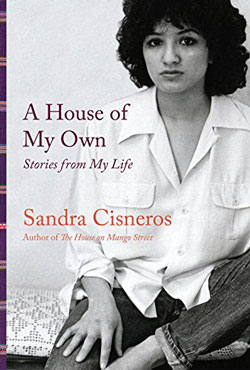

A House of My Own: Stories from My Life

by Sandra Cisneros

reviewed by Laura Albritton

The title of Sandra Cisneros’s new book, A House of My Own: Stories from My Life, echoes that of the 1984 novel that brought her literary fame, The House on Mango Street. That book chronicled the efforts of Chicana adolescent Esperanza Cordero to grapple with her Chicago neighborhood, her family’s poverty, and the difficulties of growing up—experiences that, to some degree, mirrored the author’s own. In this collection of essays and talks, however, Cisneros asserts that the memories she presents “are a way of claiming my real life and differentiating it from my fiction, since there seems to be so much out there assumed or invented about me.”

The concept of home pervades A House of My Own and gives the collection cohesion. The first piece, “Hydra House,” describes the Greek island home where the writer finished The House on Mango Street.

Like all Greek houses, it was whitewashed inside and out with lime each Easter. It had a high garden wall, thick walls, gentle lines, and rounded corners, as if carved from feta cheese.

Cisneros underlines how vital it was to have her own space: “I was creating. I had my own money. And, I had a house of my own. This to me was power.” The enchanting Argo-Saronic isle of Hydra is as geographically and culturally distant as can be from her novel’s setting of Chicago, but Cisneros quickly establishes the importance of achieving independence from and perspective on one’s roots. Discussing writers Thomas Wolfe and Betty Smith in another piece, she notes, “So often you have to run away from home and visit other homes first before you can clearly see your own.”

Each section begins with an introduction by the writer from the vantage point of the present, and it’s intriguing to see this dialogue between the aspiring artist she was decades ago and the experienced, successful writer she has become. Cisneros offers generous tributes to authors whose work has been important to her, from Marguerite Duras and Eduardo Galeano to the poet Luis Omar Salinas. Among the most appealing aspects of A House of My Own are the insights Cisneros offers from other creative people, as when she quotes Salinas saying,

There has to be some kind of tension, some kind of conflict. Most writers are at odds with their environment or at odds with themselves. For the poetry to be of any consequence, the poet must have a fight on his hands.

The artist at odds with her environment is another theme that figures prominently in the book. Cisneros writes movingly of her father’s lack of interest in her career, and how his main ambition for her was that she find a husband. In the essay “Only Daughter,” she admits, “In a sense, everything I have ever written has been for him, to win his approval even though I know my father can’t read English words.” When he finally does read a story of hers translated into Spanish—one about the place where he grew up—his attention is at last wholly focused on her writing. As he finishes, he asks, “Where can we get more copies of this for the relatives?” It’s a touching moment of acknowledgement.

A House of My Own depicts Cisneros’s struggle for autonomy from the psychological, financial, and familial forces that might have made a writing life impossible. She relates how her mother’s sense of not belonging influenced her:

I became a writer thanks to a mother who was unhappy being a mother. She was a prisoner-of-war mother banging on the bars of her cell all her life. Unhappy women do this. She searched for escape routes from her prison and found them in museums, the park, and the public library.

We learn in Cisneros’s essays how, as an artist, she created homes for herself, houses that she decorated with beautiful and meaningful objects, but also how she created a space for herself in the world where she felt a sense of acceptance and belonging. The paradox of her story is that each home is both a sanctuary and an escape.

A House of My Own will appeal to the many admirers of Cisneros’s writing and to writers and artists who find themselves struggling against everyday obstacles that keep them from their work. It contains a great deal of wisdom, shared in Cisneros’s characteristically frank yet compassionate prose; as Cisneros tells us, “I’m convinced that if we’re to be artists of any worth we must lock ourselves in a room and work. There are no two ways around this one, no shortcut, no magic wand to save the day.”

Published on March 15, 2016