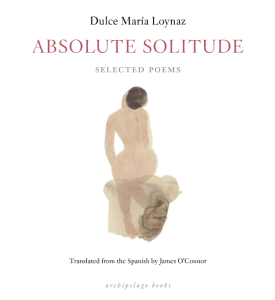

Absolute Solitude

by Dulce María Loynaz, translated by James O'Connor

reviewed by P. Scott Cunningham

Born to a wealthy family in 1902, Dulce María Loynaz was a celebrated figure in Cuban letters before the revolution, publishing multiple collections of poetry and one novel, all of which were well received. After the revolution, she became a ghost, living like a hermit in a mansion in the geographic center of Havana. As neither a state-supported writer (she never publically endorsed Castro) nor an enemy of the state (her work is not overtly political), Loynaz was allowed to exist but not to flourish. Other Cuban poets made pilgrimages to her home, but Loynaz herself rarely left.

That a poet like Loynaz could exist, at once cut off from the literary world and vibrantly attached to it, was neither strange nor notable in Cuba under Castro, a place where the whole of society survived in the gap between official decree and unofficial practice. In a further twist of irony, Loynaz also served for years as the president of the Cuban branch of the Real Academia Española, the organization dedicated to promoting linguistic unity in Spanish-speaking nations. Quite literally, the group was formed and funded by the Spanish Crown so that the residents of these countries would always be able to read Cervantes, a Quixotic mission if ever there was one. Her post probably had something to do with her winning Spain’s illustrious Cervantes prize at the age of 90, but for someone who had suffered so long from external political forces, Loynaz was due a turn of the wheel. Rescued from obscurity, Loynaz enjoyed a few subsequent years of literary fame and then died in 1997 at the age of 94.

Her journey into English is thanks to James O’Connor, an American translator who went to Cuba looking for an emerging poet and discovered a submerged one. His devotion to her is obvious, which is appropriate for a poet who is, by nature, devotional herself. Loynaz’s poetry has a Keatsian elegance and burn to it. She writes in a high romantic register that trades heavily in well-worn poetic subjects: souls, flames, darkness, roads, skies, beauty, etc., which is to say that her work is always clear and serious and does not waste time on trivial states of being.

My bones ache. The very blouse on my back aches. And my solitude aches, too, ever since you let me press my mouth to it and blow it into flame.

This is heavy stuff and treads dangerously close at times to a parody of itself. It sounds florid in English, and even more so in Spanish, but is rescued by the tough-mindedness of the poet, a fortitude exemplified (in this volume at least) by her abandonment of the line in favor of the prose poem. If Loynaz approaches romantic love on the life-or-death spectrum of a Catholic, she also approaches it with the realism of a philosopher.

I wouldn’t trade my solitude for a little love. For a lot of love, yes. But a lot of love is itself a kind of solitude.

Her best work has a darkness to it that sometimes prefigures Alejandra Pizarnik. In lines like, “I am not I. I am barely my own shadow,” and “I fear nothing so much as ceaselessly being myself,” Loynaz hints at the bottomless depth of the psychological world that Pizarnik later spelunked. Loynaz’s pain is not its own uncontrollable animal however, but a symptom of the depth of her feeling for the world. Here’s an entire Loynaz poem:

You took the lamp with you, but the light stayed with me. Or something more subtle and tenuous, like the light’s shadow.

Her legacy, I think, lies in her mastery of the very short poem, a genre that has few acolytes and even fewer masters. I resist reprinting too many here, because it seems a disservice to the publisher, but they are the moments in the book when Loynaz seems most at home in her poetic self. It’s almost as if her materials are so large that she can only use a few of them at a time, or else they spill out of frame and become nonsensical. Here’s one more because it fits the theme:

I have been cutting my poetry so much that I have reached the pit without tasting the fruit.

My one quibble with O’Connor’s otherwise excellent translation is his failure at times to find an imaginative solution for a tricky word. “He ido descortezando,” which he translates as “I have been cutting,” is literally a combination of “I have stripped” and “I have peeled back.” “Cut” is nice in English because it’s already both a term of revision and of cuisine, but much is lost in its selection. I’ve never heard any poet say, “I’ve been cutting my poetry,” and the image of the fruit being slowly reduced to its seed with one’s bare hands is lost at the expense of the lesser goal of a double meaning.

This volume, published by Archipelago, combines Loynaz’s 1953 collection Poemas sin nombre with another group of her prose poems published posthumously in 1997. It’s remarkable to me how consistent the two groups of poems feel beside one another, as if they’d all emerged at the same time but were unpacked from different boxes. Loynaz worked for years on what we’d call now the same “project,” but to her it probably just felt like a part of her existence. In a speech she gave in Havana in 1950, she compared poetry to the bread common people eat with every meal. Little did she know then that she’d soon be cooking for one. “There was a humble sadness without you,” she writes, “which nobody seemed to notice, like a puddle that reflects the sky all day long.”

It’s good that Loynaz is back out in the light, and now, across the water.

Published on December 2, 2016