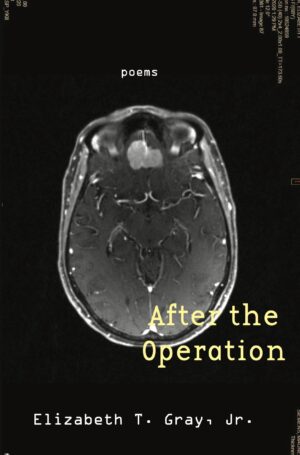

After the Operation

by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr.

reviewed by Maryn Gardner

In After the Operation, Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr. recounts what comes after the removal of a brain tumor. Weaving together hospital records, personal journal entries, visitor reactions, and fragmented memories, Gray showcases the struggle to make sense of oneself after the trauma of brain surgery. The collection’s poems attempt to parse out the new contours of Gray’s post-op mind, mapping her brain’s “occluded topography: eloquent fissures, ridges, reconfigured.”

Gray is familiar with topographical exploration—her first collection, Series | India (2015), follows a pair of Western travelers across the landscapes of India, while her second collection, Salient (2020), spatializes the field terrain of the 1917 Battle of Passchendaele in Flanders. Gray’s acute sense of geography and space is put to new use in After the Operation, as she charts out her interior neural topography. Her spatial markings alternate between poetic and scientific language:

The pterion, in the temporal fossa. Site of the convergence of

important plates: the parietal bone, the temporal bone, the frontal

bone, and the greater wing of the sphenoid bone.A structural landmark for neurological access.

The weakest part of the skull.

From pteron, meaning wing or feather.

The precise location where trickster Hermes’s wings were.

The neuroanatomical language of these lines blends with the mythic, mimicking the unreality (to many) of surgically opening the brain and taking something out. In plotting the brain’s neural landmarks, Gray makes visible the mind’s hidden rivers and valleys, as well as its vulnerabilities. Inside the skull lies an “unstable geology”: Where is the boundary between self and the other? Between mind and body? Between internal and external? In the limbo of Gray’s post-op recovery, “her mind became an uninhabited coast,” a liminal space of fragments and unknowns.

Gray counters her experiences of disorientation—both physical and mental—with the precise annotations of the neurosurgeons. Their methods of mapping the brain are technological and concrete:

The Brainlab system was used to

map the trajectory to the lesion and to map the

frontal sinus. The incision was a curvilinear

standard pterional incision. The incision was

then clipped, prepped, draped in the usual

aseptic fashion.

The neurosurgeon’s tone and vocabulary stands apart from Gray’s poetic narrations, but the medical notation still carries a poetic quality. Together, Gray’s mythic invocations and the neurosurgeon’s highly technical language convey a neurological poetics as they seek to characterize the form and content of the brain.

After the Operation opens Gray’s mind for dissection and exploration. Readers witness her attempts to find coherence and meaning in fragments, as she peels back the curtain on the mind, peering into the skull, exposing its fragility.

At one point, Gray likens her mind to an Egyptian tomb, interweaving the surgeon’s description of the procedure with Egyptologist Howard Carter’s journal entries detailing the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb. Here, the neurosurgeons turn into archaeologists, digging “through layers / of dura sealed / with talismans, cartouches into / my never-violated dark” until, finally, “The tumor has been carefully removed / The chamber has been resealed,” and “The embalmed tumor / floats somewhere in a canopic jar.”

The tumor itself is both treasure and terror, a “yellow crystalline sandstone” that was at once part of her and a threat to her. In the glimmering gloom, Gray confronts the death of a piece of her, along with the confusing terror of the exposed brain, asking:

When they come for you, when the unfamiliar roar comes, and a

sudden opening, and light pours in, when what had kept you safe,

what had always been, is breached, pried open, and light pours in,

what do you want to have been writing then?

But even “after the operation, the desolation was not behind her.” Gray’s sparse, candid poems continue to wrestle with the grief of recovery. She reports losing memories, losing nerves, losing her sense of smell, and losing friends. She also reports seeing mysterious birds, forest mirages, volcanic calderas, and piles of blue feathers.

Amid the “gaps” and “riverbed of gravel” in her mind, she struggles to put herself back together. Eventually, she looks anew at what remains after the operation:

What had been fragments

started to lookwhole, …

narratives in their own right

into which I dove, returningto the surface with treasure:

a phrase, leaf, pearlsa harvest of shards, the task

not to reassemblebut to embrace each flake:

In After the Operation, Gray eventually rediscovers herself and the world—which are perhaps one and the same. At the end of a long recovery, the collection offers a hint of peace: “No glint of helmets / No campfires anywhere.” Her one-year post-op scans are clean, and so on goes the after.

Published on September 18, 2025