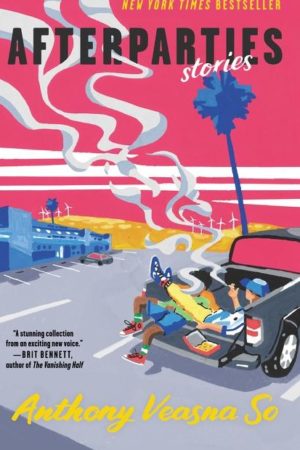

Afterparties

by Anthony Veasna So

reviewed by Richard Scott Larson

Anthony Veasna So’s razor-sharp and wholly original debut, Afterparties, poses a question in its opening story: “What does it mean to be Khmer, anyway?” And this is a question So’s characters will grapple with throughout the collection. At the heart of these nine excellent stories is the generational divide in a Cambodian community in California’s Central Valley, which consists of refugees from the Khmer Rouge regime and their mostly American-born children, living in the shadow of the genocide their parents and grandparents escaped and figuring out what it means to be Khmer while sometimes thwarting the expectations of their elders.

“Maly, Maly, Maly” finds its queer male narrator, Ves, and his female cousin, Maly, facing two very different futures. Ves is heading off to college at the end of the summer to escape the suffocating influence of his community, while Maly will stay behind to live a very different life—the life she’s always known. But first they are to celebrate the rebirth of Maly’s dead mother’s spirit into the newborn body of their second cousin’s daughter, who will be blessed by monks in accordance with Khmer Buddhist beliefs about reincarnation. (Maly’s mother, “an immigrant woman who just couldn’t beat her memories of the genocide,” committed suicide many years before.) The traditional practices and beliefs of Ves and Maly’s ancestors rub up awkwardly against their lived experience as the children of refugees who are trying to keep their conflicting identities intact, and So’s achievement is in describing the liminal space between past and future, old ways and new.

Several characters appear in multiple stories, a clever way of opening up this community to readers, emphasizing its closeness as well as the claustrophobia experienced by some of those within it. The infant burdened with the spirit of Maly’s dead mother Somaly returns in another story as Serey, a twenty-something nurse working in the Alzheimer’s and dementia unit at an elder-care facility. Here she looks after Ma Eng, the woman who had presided over the reincarnation celebration decades before, with the tangled web of relations in this insular community simulating how the connections within large families sometimes don’t make sense to outsiders. Maly’s obvious resentment toward Serey, whose body supposedly harbors the spirit of Somaly, gives the story its edge, as do Serey’s nightmares leading up to Ma Eng’s death. In these nightmares, she often finds herself literally embodying Somaly during her escape from the Khmer Rouge:

All week my nightmares as Somaly stay unbearable. Every night, I flee through the mine-encrusted forest. We are traveling as a group, a family, but half of us are dead. I clutch an infant Maly. My grip bruises her flesh and she cries and yells, but there’s no other way to lock her in my arms as I am running as fast as I can to reach a border, any border …

In the end, Serey is granted a reprieve from her nightmares. On the day of Ma Eng’s death, she gifts one of Somaly’s necklaces to Maly’s young daughter, Sammy, literally handing over what she believes to be the source of her burdens. At first, she considers destroying the necklace and thus severing her family’s ties with its dark and complicated past, but she ultimately can’t bring herself to do it. Instead, she chooses to pass on Somaly’s pain and trauma to the next generation.

The collision between queer sexuality and cultural expectations is another major source of anxiety in many of the stories in Afterparties. As an older Cambodian boyfriend puts it to the young, adrift narrator of “Human Development,” “[W]e don’t have the privilege of wasting time—not anymore—not with the stuff we’ve survived.” Similarly, the narrator of “The Shop,” another post-college queer man who can’t envision a future for himself considers the responsibility to procreate: “The only time I took the idea of kids seriously was when I thought about everyone who had died, two million points of connection reincarnated into the abyss, how young Cambos like me should repopulate the world with more Cambos.”

When his father’s car repair shop ultimately falls on hard times, the community calls on the monks for a blessing. The narrator announces his intention of saving the shop, but then he has a realization: his father only stayed in business to give his children a brighter future than his own. Paradoxically, staying to help save the shop defeats the purpose of what his father had been working toward all along. This is the kind of grace note that So hits in his breathtaking endings, the craft behind the stories in Afterparties remaining invisible until everything clicks into place.

At the end of “The Monks,” a recurring character named Rithy is being driven home after a brief stay at a temple to complete a ritual honoring his dead father. He notices the temple shrinking behind him in the side mirror of the car, the details fading to the point that he can only recognize the building by its outline. “I wonder if that’s all you can know about someone, their outline,” he thinks. “I wonder what will end up as mine.” To see a debut as promising as Afterparties being published posthumously is to see the outline of what might have been. This debut is tragically forced to double as a bequest, much like the necklace Serey passes down to Sammy—a gift that comes with its own ghosts, as well as the responsibility to remember those who are gone.

Published on October 12, 2021