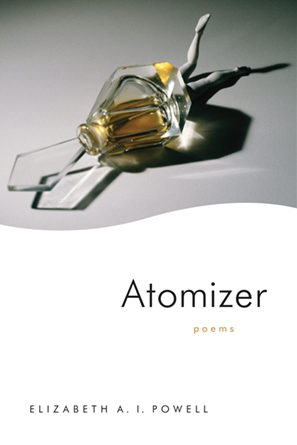

Atomizer

by Elizabeth A. I. Powell

reviewed by Alexandra Mayer

Atomizer, Elizabeth A. I. Powell’s latest collection of poetry, begins with an invocation to the muse of perfumery: “Let the atomizer do what it does best: release the distance between autobiography and critical analysis.” Powell pumps “Atomizer”—the collection’s opening poem—full of scents and aromas. Amid the fog, her speaker’s memories and obsessions and desires begin to take shape. Olfaction is everything to Powell. She even uses it as a structuring principle, splitting the poem into three sections that follow perfumery’s concept of fragrance notes. “Top notes” are the first whiff of a perfume, which evaporate quickly. “Heart notes” follow from top notes and are, appropriately, the heart of the aroma. Finally, there are the “base notes”—what endures when the top and heart notes fade away.

But how do the top, heart, and base notes actually work as sections of a poem? On the surface, “Atomizer” tells us how we ought to make sense of its form: “top notes introduce an idea,” “heart notes are the distinctive aspects of the perfume,” and “base notes are the subtext.” However, Powell disrupts this neat explanation with images and languages that recur throughout, blurring the lines between the notes. Take, for example, the following stanza, which is repeated verbatim in each section:

Love has many scents. He used scent to confound, to throw me off the trail of who he really was, which may be just another word for emptiness. How he found the scent that described my memory to my desire and it smelled so good I had no choice to but to love him when his cheek slipped next to mine.

Drawing on the concept of Proustian (involuntary) memory, Powell emphasizes how language, sensual experience, memory, desire, and the self are all entangled, one bleeding into the next. Proust is a key reference for Powell, whose work she figures in terms divine: “Fragrance summons angels. I desire Proustian angels, different from Episcopalian ones.” Which is to say: she wants angels that walk, talk, smell, and remember like humans do, as opposed to Christianity’s more supernatural variety.

Proustian angels lurk in the corners of every page of the book. “Atomizer” the poem functions not only as an introduction to the collection, but also as a microcosm of it. No matter where Atomizer’s pages take us—childhood summers on a farm; a baseball game; online dates in Burlington, Vermont; a trip to Lithuania—they always circle back to the interrelated nature of sensual experience, memory, desire, and the self. Atomizer also uses the structure of fragrance notes: the first nineteen poems are “top notes,” followed by seven “heart notes,” and finally eight “base notes.” That there are twice as many top notes speaks to Atomizer’s cerebral qualities—its poems often linger in the theoretical, and do not shy away from literary, historical, and cultural references. But Atomizer is not a collection that takes itself too seriously; Powell’s speaker also has a killer self-deprecating sense of humor.

As with “Atomizer” the poem, Powell never gives us the key to unlocking the top, heart, and base note structure of the full collection. Rather, in trying to parse the structure, what emerges is a profound disillusionment with structures and forms themselves, especially poetic forms. “Ars Poetica,” one of the early top note poems, shows us how the speaker’s mother teaches the speaker that language can be scrubbed and perfumed into submission:

My first real speech rose scented

off of a cake of soap,

molecule congealing in my salivary gland

that held the mellifluous

obscenities I spoke, the words my mother found

horrid, disrespectful, utterances I loved

The speaker carries this lesson forward into adulthood. To her great frustration, perfumed language becomes entangled with her sense of self and with her sense of her own womanhood. Playing with the trope of feminine duplicity, Powell codes perfumery as a form of lying or disguise, set at odds with her notion of “real speech.” Poetry is not only implicated in this perfumery, but also seems to be a destructive force. Like an atomizer, a poem “disperses” the existence of the speaker, “separating it into parts—words, sprays, / dots of color, scents.” But ironically, it’s through this perfumed poetry that Powell begins to access “real speech”— even if the access is always incomplete.

Powell extends her interrogation of structures and forms into myriad aspects of life, like cis heteronormative relationships, consumerism, the twenty-four-hour news cycle, white liberal “Coastal Elites,” and cinema verité. Although Powell’s poems are very much invested in the body, this focus on structures does often lend them an abstracted feel. Like “real speech,” the real world often seems beyond the speaker’s grasp, perhaps a reflection of her white “Coastal Elite” positioning. But multiple times throughout the collection, Powell lambasts affluent liberal whiteness for its superficiality and hypocrisy. In one poem, the idyllic Vermont landscape is stunned by F-16s flying overhead, causing the speaker to remark: “We are always at war now. We don’t know when to be afraid.” It is only when the war comes to their home that this demographic begins to grasp the unceasing violence of American imperialism.

Although Atomizer was likely written in advance of the coronavirus pandemic, the collection presciently speaks to the current moment through its interrogation of structures. Coronavirus has underscored the systemic conditions that make life so precarious for a majority of Americans, and Powell’s poems encourage us to consider what these systems smell like in the air and on our skin. How do hegemonic forces perfume daily life? What kinds of duplicity do they enact on our bodies and our minds? In drawing out these questions, Atomizer clears the air for us to imagine a new reality.

Published on June 14, 2021