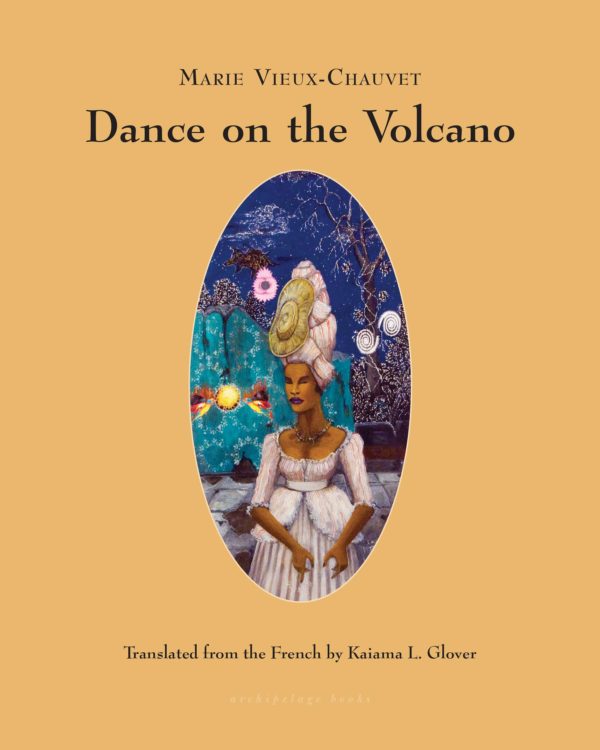

Dance on the Volcano

by Marie Vieux-Chauvet, translated by Kaiama L. Glover

reviewed by Victoria Zhuang

The people of this novel behave like knives thrust into a back: cutting and fast, resolved to be merciless, falling as if compelled by the universe. They keep their mouths shut otherwise. To be careless, even in a moment of vulnerability, is to risk breaking the spell and learning there is no way home. These are Marie Vieux-Chauvet’s residents of Saint-Domingue before Haitian independence: the slaves, the free black landowners, the Creole people, the whites rich and poor. All races, all classes in this colonial cauldron, are viciously pitted against one another. Their peace is thin; their confrontations, lava-like.

Vieux-Chauvet was one of the great female Haitian novelists of the twentieth century, though she is little known outside the Caribbean. In Dance on the Volcano, she gives us, among all this chaos, a plot that moves with supple speed through reversals and showdowns like the finest of thrillers. At the center is Minette, the novel’s pièce de résistance. A young soprano based on a historical figure, she is the first person of color in the island’s history to perform on the stage of the prestigious Comédie opera house. Minette is born mixed-race, socially respectable and free. But as she comes of age, she learns the crippling truth of her family’s origins in bondage. In dark times on the island, she comes to accept her artistic and political destiny with iconic fortitude.

It is a great novel, and English readers are fortunate that a long-overdue second translation this year from Kaiama Glover is, for the most part, elegant and clear. Glover has a handle on the more subtle turning points of the novel, as when a slave publicly begs his wealthy owner for mercy:

“Oh, Master, you were so proud of my strength and my endurance. You called me your good Congo and you spoiled me. But now, Master, I’m disabled. You won’t sell me like the others, Master, you aren’t going to sell me?”

“We’ll have to see, Michel, we’ll see,” said the planter in an annoyed tone.

The annoyance of Vieux-Chauvet’s planter, his show of indifference at having his time wasted, his humiliating dismissal, and the magnitude of his lie to the slave who had trusted him—all this, Glover relays in spare strokes. Minette, who has been watching from a distance at the planter’s evening ball, feels sickened. “The truth suddenly hit her, though she pushed it away.” She was invited as a celebrity honor. But now she discerns the real reason: to be baited, mocked, and disposed of like the servant.

Only the use of Creole seems less successful in this translation. For example, when Minette lashes out privately at the white colonial rulers of the island:

Her mama, her mama had suffered such things! Oh, the evil of the white man, oh! What swine! Galley slaves and white trash! Every Creole swear-word she could think of passed her lips.

“Oh!” and “swine” seem priggish, out of character for the bold Minette. “Galley slaves” does not make sense as an insult from a slave descendant to the slave-owner class. “White trash” in English has a specific cultural origin in urban America, so it does not transplant well here either and feels ineffectual.

I would have liked to see Glover retain some Creole words as a nod to the unsettling role of the original language. The zigzags between French and Creole dialogue on the page must have felt jarring to French readers. Mirroring the absolute separation between the races and social destinies of their respective speakers, these contrasting languages would have brought out the novel’s central effect of continuous tension and class opposition. Glover retains French titles like “Monsieur de Caradeux” and phrases like “vis-à-vis” throughout, so she understands the need to honor untranslatability. But she hardly does the same favor for Creole—“lambi,” a local word for horn, is a rare exception. Instead, Glover only indicates at times that a character is shifting tongues and leaves it to the reader to infer or estimate precisely which words are being said in Creole and when. Muted by its English context, the book’s Creole presence is an afterthought. The result is a minor but significant loss for readers.

Notwithstanding such limitations, in this translation Vieux-Chauvet’s work is still a tour de force. The plot verges on operatic, but this mood is earned by the chasm-like grandeur and darkness of its people and time. It’s a book whose people demand elevation, but also, finally and more importantly, courage. Every act of mere violence in the novel is an act of retreat. Every moment of love given, however tragically it ends for the giver, feels like a motion forward.

Published on February 21, 2017