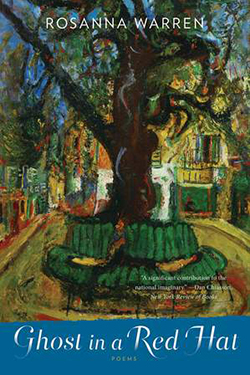

Ghost in a Red Hat

by Rosanna Warren

reviewed by Paul Franz

Ghost in a Red Hat is Rosanna Warren’s fourth full-length collection of poems, appearing some seven years after her last collection, Departure. Ten years separate that volume from its predecessor, Stained Glass, and another twelve lead back to the 1981 Each Leaf Shines Separate. Though these intervals represent steady activity, including translation, editing, and criticism, they nonetheless suggest some of the qualities of her work: its attendance upon the adequate occasion and multilayered artistry. Tending toward an expansive free-verse line, Warren’s newest book has stylistic affinities with Departure, as opposed to the tighter, more traditional patterns of her first two books. At its best, it achieves a delicate balance between structural solidity and movement.

The opening lines of the book take us into a middle of things that is also the moment of their vanishing: “—when she disappeared on the path ahead of me / I leaned against a twisted oak, all I saw was evening light where she had been.” The first poem’s title, “Mediterranean”—the sea between landmasses—here evokes the middle of Dante’s road, the midpoint on the homeward journey of Virgil’s Aeneas. For those two wanderers, crossing the halfway mark requires a trip to the underworld. For Warren, whose underworld is memory and language, the gates are a punctuation mark, a colon:

where she had been:

gold dust light, where a moment before

and thirty-eight years before that

my substantial mother strode before me in straw hat, bathing suit, and loose flapping shirt.

Those echoing prepositions—“before,” “before,” “before”—point to the thematic core of Warren’s latest work. Like the Ancient Greeks, Warren is able to see the past as in front of her, if only for an instant. Such temporal rifts center the volume’s concerns with a present that has endured beneath the threshold of notice, that comes into its own when conflict or illness threaten to make it the past, that becomes the past, stranding the survivor in a new present of uncertainty and questions.

Warren’s latest poems tend to veil their complexity in understatement. Resonant use of verbs and adjectives often replaces metaphor and simile. When the latter do appear, they are usually keen visual likenesses, attesting to Warren’s training as a painter: “Pernod light”; “the gray, dry stogie / of an owl pellet.” Though remaining within the bounds of realism, such images often have an expressive, gestural force. Also contributing to the heightening of the language is its sound patterning, especially its acute sense of rhythm, not only at the level of the individual line, but also in the contours of longer phrases. Much depends upon arrangement. Passages of description often introduce obscurely necessary delays or diversions in the main current of thought. Warren’s syntax, too, can reflect an occult sense of overriding purpose. Though some poems strikingly foreground parataxis, or grammatical clauses abruptly set beside each other—as in the prose snapshots of “Odyssey,” or the moment of self-interrogation in “After,” on Hurricane Katrina—this is not the book’s most prevalent mode. “Fear” and “Porta Portese,” its most syntactically fractured poems, feel oddly restrained, the technique not carried far enough. Most of the book’s stronger poems combine such brevity with a tug in the opposite direction, toward hypotaxis, or grammatical clauses arranged in complex layers. The large-scale interlacing of the two styles in “Water Damage” and “Earthworks” at times loses its tension; the poems’ loose unrhymed tercets, though hospitable to their documentary material, can place the language under too little local strain. And yet, many other poems find the precise center of gravity to suspend their finely articulated elements.

One such poem, “Mistral II,” appears early in the volume. The second of two poems on the cold northerly wind that blows through southern France, it follows a prayer for new beginnings. Its opening moves announce union with the element: “I gave myself to the mistral, which had shouldered its way / down from the north, leaping the careful fields of France…” The sentence careens through several more enjambments until the wind snatches away the poet’s page. The next lines register apprehension, then shift to a distancing voice: “we will all be changed in the quiet garden.” But the poem cannot rest in generality, yielding instead to a hope perhaps fulfilled in its own cresting and subsidence:

I have broken some forms, I am waiting to see

what survives this tumult of leaves

and cloudlight, what the sea will whip up from its jagged troughs

when spray shatters against the downward slicing veins of schist

and the hills bracing the valley wuther and groan.

Then nothing happens: “the garden stays pegged to the earth,” the poet stays motionless. Warren’s last, striking turn, however, shifts the focus of attention from the actual to the potential—a potential discovered in the past that remains open in the final, suspended conditional:

but it was I who prayed

yesterday to make this refuge cry with a different breath,

hoping some new word would be snatched up out of my throat—

Its salt tang could be from sea wind, could be from tears.

Here, once again, Warren moves into the future facing the past. At their best, the poems in her latest volume only begin to reveal themselves in a mixture of foresight and hindsight, through rereading after rereading.

Published on May 16, 2013