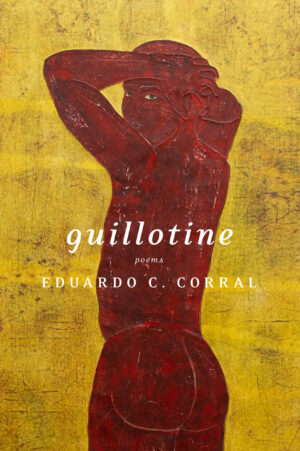

Guillotine

by Eduardo C. Corral

reviewed by Katie Berta

Eduardo C. Corral’s second poetry collection, Guillotine, is a complex examination of the body as the principal site for pleasure, pain, violence, and everything that goes on in the intellect. In Guillotine, sometimes the body experiences all these at once.

As Corral tells us in “Testaments Scratched into a Water Station Barrel,” the collection’s second section, “Bodies, in the Sonoran desert, / are everywhere.” “Testaments” is a long, polyphonous series of persona poems in which we’re asked to imagine that shifting speakers, on their way across the desert between the United States and Mexico, have scratched their narratives, layer after layer, into a water barrel. Corral moves between their disparate experiences in the desert—disparate, though they are often experiences of violence or deprivation—and the lives and voices they carry with them through their passage. This poem’s speaker means it literally: bodies are everywhere—tortured bodies as well as the body that holds the memory of each person’s life. He observes

a headless corpse

sporting a T-shirt

that reads: Superstar.

A severed hand,

black yarn around

the thumb.

Hundreds of people, forced to negotiate the most treacherous parts of the desert by more and more restrictive immigration policies, die trying to cross the US-Mexico border every year. Often, their bodies will never be identified. Much of the power of “Testaments,” then, is in the way it imagines the lives and consciousnesses that preexisted the crossing—and sometimes the experience the person had as they died. “Apá, dying is boring,” the section begins.

To pass las horas,

I carve

our last name

all over my body.

The violence these speakers experience is balanced by their experience of sensuousness. Yes, the poems are concerned with the brutal crossing they describe, but also with the whole life of their speakers. “I almost eloped with my second cousin plastic / barrettes in the shape of the Eiffel Tower / keep her bangs from her eyes,” remembers one.

She bathed

a trumpet

in milk

her tenderness acoustic

& plural

her pupils perched

in all that green,

recalls another. Corral imagines himself into his subjects’ bodies and minds; his poems restore identities to people who have been brutalized into anonymity and personalize the experiences of migrants to readers who may otherwise think of them as statistics.

Corral doesn’t limit his concern to the tortured body, though pain is central to the way he occupies his own body, and to his conception of desire. Even in “Testaments,” in which the speakers describe their emotional and physical devastations or their deprivation in the harsh environment, the poems are punctuated by an insistent sexuality that is counterpoint—or maybe counterpart—to the violence. This relationship carries through the rest of the text. The book begins with the single poem, “Ceremonial,” which describes the speaker pinching

a mole

on my skin, pull[ing] it

off, like a bead—

I pinch & pull until

I am holding

a black rosary.

The speaker is “delirious, / touch-starved,” and thinking of “A copper- / faced man” who “once / called me beautiful.” The confection of pleasure and pain, here, comes in part from the speaker’s desire and in part from his shame.

Stupid,

stupid man.

I am obese. I am

worthless,

he says, refusing to believe he is beautiful. Then:

I can still feel

his thumb—

warm,

burled—moving

in my mouth.

His thumbnail

a flakeof sugar

he would not

allow me to swallow.

For Corral’s speaker, these are the two sides of desire. You may lose yourself in your present, so absorbed that you believe the lover can be consumed; you may also be so aware of yourself as seen by the other, or of your body, that the encounter feels unbearable. In “Ceremonial,” the speaker ends up so “desperate / for the sting of snow / on my skin” that he

walk[s] into

a closet, crawl[s]

into a wedding dress.

Oh Lord,

here I am,

he says. Later, in the poem “Autobiography of My Hungers,” the beloved’s beard is “an avalanche of honey, / an avalanche / of thorns.” In “’Around Every Circle Another Can Be Drawn,’” the speaker “kissed a guy who called me a f[*****] once or twice a week. / I still see his voice: / six hummingbirds nailed to a wall.” “If you think I look good naked wait until you see me dead,” one of the voices in “Testaments” says. In “Postmortem,” one voice asks, “How did you meet?” “He stepped on my face, he stepped on my teeth,” answers the other. In each of these poems, pleasure and pain intermingle to create something new, a yearning that can’t be satisfied.

Even as he develops these threads of desire, Corral returns Guillotine to the experience of the people attempting to cross the border now. The book ends with them. The last poem, “To Juan Doe #234,” assumes the voice of the sibling of one of the deceased. The speaker says:

I only recognized your hair: short,

neatly combed. Our motherwould’ve been proud.

In the Sonoran Desert

your body became a slaughter-house where faith & want were stunned,

hung upside down, gutted.

As with all the speakers of these poems, there is no relief from that want—it is frozen, “hung upside down,” like the body of an animal, poised to be consumed.

Published on February 1, 2021