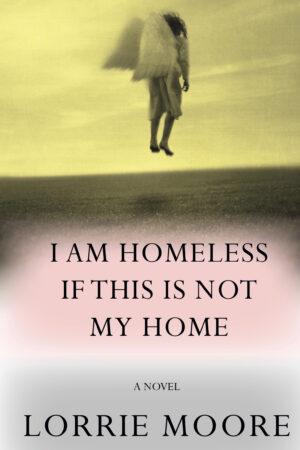

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home

by Lorrie Moore

reviewed by Hamilton Cain

Like a Möbius strip or an Escher drawing, Lorrie Moore’s fiction has long zigged and zagged and bent the world to its own gravity, forging a reality beyond the realism so dominant in the American literary landscape. “Real Estate,” from her collection Birds of America, opens with three pages of “HAHAHA,” a woman’s reaction to her husband’s infidelities—is she literally laughing her head off?

Moore’s weird, wondrous new novel, I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, her first in fourteen years, clocks in at under two hundred pages; in fact, it is two discrete stories that are inextricably bound together. In 1871, Libby is an innkeeper on South Sunken Road, a rural corner of the former Confederacy. Like many Tennesseans, she was a Union sympathizer during the Civil War but kept her abolitionist views to herself, lest she lose her “seccesh” clientele. She writes a series of letters to her dead sister, collecting them in a binder. One handsome boarder, Jack, parries wits with her. Moore implies sexual intimacy, but Libby is discreet in all things: “A good scalawag sticks to her diary.”

Set weeks before the 2016 elections, the book’s other plot revolves around Finn, a high-school teacher who drives from the Midwest to visit his elder brother, Max, who’s languishing in a Bronx hospice facility. Finn is full of regret: for his childhood apathy towards his sole sibling; for a failed romance with a crazed lover, Lily; and for a nation toying with the idea of elevating an incompetent vulgarian to the presidency. Still, his bedside presence sustains his brother. “Chemo or cancer—who could say?—had eliminated not just the hair on his head but the sprinkle of moles on his neck; his skin was buttery,” Finn observes. “He had the smooth hue of an apricot. He was a manila envelope getting ready to be mailed … Max closed his eyes and seemed to fall back into the upside-down world of the sick.” Then Finn gets a call about Lily, summoning him home. He hits the road.

With her trademark wordplay and grammatical twists, Moore toggles between timestreams, divining the “reality of the unseen,” to borrow from William James. Libby rightly intuits Jack’s attraction to her servant, Ofelia, and yearns to pierce his aura of mystery. Finn, disconsolate and still in love with Lily, seeks her out even beyond the grave, finding her restless outside her final resting place, translucent in death, skin and hair speckled with mud and worms. She’s half-decayed but somehow still herself: sarcastic, hilarious, desiring him, as fiercely imagined as Cormac McCarthy’s suicidal Alicia Western in his last novel, The Passenger. Lily persuades Finn to drive her to a body farm near Knoxville, where she’ll shuffle off this mortal coil for good.

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home picks up speed as the couple meander across a geography both real and surreal, of interstates and two-lane highways populated by eighteen-wheelers and little else. It always seems to be nighttime. If I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home is in conversation with another novel, it’s George Saunders’s Booker Prize winner Lincoln in the Bardo; Lily even describes her dilemma as a “bardo,” a state of limbo between death and rebirth. But Finn is determined to haul her back into life.

Exhausted, they crash at the South Sunken Road Inn, with its antique furniture and its ghosts, a Tennessee version of the Hotel California. Here Moore briefly stitches her two narratives together. The innkeeper bears a creepy resemblance to Libby, who, in another era, plots vengeance against Jack; Moore reveals him to be a famous assassin who’d escaped the hangman’s noose. Libby senses Finn and Lily as well: “At times like these I often feel the growing romantic curtain being lowered over the war,” she notes. “The many vibrating worlds in front and behind, within and without, intersecting and yet not intersecting.” Call it string theory as narrative technique.

I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home peels back the many layers of mourning. Finn vows “to take his own grief elsewhere and spend it in the world until it was a thin, tinny pang”—but the book is also an elegy for a country with a gun to its head. Moore confronts us with the maddening, irreconcilable differences that again threaten our union. Like Cormac McCarthy in his last novels, she’s reflecting on the futility of literature in the face of oblivion, the act of writing itself a kind of bardo.

Published on July 27, 2023