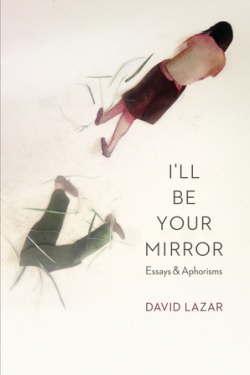

I’ll Be Your Mirror: Essays & Aphorisms

by David Lazar

reviewed by Debbie Hagan

David Lazar is known as a fearless crusader for the “transgenre” essay—bending and twisting the conventional essay, turning it on its head. He demonstrates this in his new collection I’ll Be Your Mirror: Essays & Aphorisms. Works in this collection are divided into three loosely-defined sections: personal essays that (more or less) follow a narrative thread; essays for the hard-core essay enthusiasts (eyes of the uninitiated may glaze over at his long explorations into the essay’s history or occasional baffling experiments); and one- and two-line aphorisms, accompanied by delightful line drawings by Heather Frise.

“Hydra: I’ll Be Your Mirror,” the title piece, comes from the book’s most elastic and challenging middle section. Here, Lazar, who teaches in the MFA program at Columbia College Chicago and is the founding editor of Hotel Amerika, explains, “the essay is the ultimate hybrid—or if you will, Hydra—form.” The “Hydra” image comes from a childhood memory of the many-headed serpent he once adored in Jason and the Argonauts. However, don’t expect this to be a personal narrative. Rather, it’s a sideways entry into an analysis of variations of essays over the past 500 years: “Is Montaigne a lyric essayist, in his sometimes elusive, elliptical, or concentric style? Or is he too discursive, standing out in the rain of explication?” He challenges the contemporary notion that essays need to be labeled: braided, narrative, lyrical, fragmented, or whatever. Why can’t they just be wild, multiheaded serpents?

Perhaps the most beautiful and (daresay) traditional essay is the first: Ann; Death and the Maiden, which tells the story of Lazar’s affair with a doctoral student who he likens to Zelda Fitzgerald—beautiful, talented, but doomed. “There were wonderful nights,” he tells us. “Lots of sex, lots of talk. Lots of music and dancing. But also: lots of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?After a while, I think we refined the bitter repartee down to the point where Albee had nothing on us.” Spoiler alert: the relationship falls apart, but they stay in touch via e-mail.

When Ann dies, Lazar questions, “Do I feel I betrayed her, and that I’m somehow responsible for the hole I feel in the world, the absence of her, even though we were not so much in touch?” This really cuts to the heart of this essay. One can’t help but reflect upon one’s own past misbehaviors, insensitivity, and foolishness in relationships. It’s easy to get sucked into to the writer’s whirlpool of guilt.

More light-hearted is “Lollipop Is Mine.” Lazar begins by telling readers he has had an epiphany, but playfully dangles it, like a carrot, edging readers steadily forward. He unravels a long-winded yarn, à la Mark Twain, meandering through varied music interests from the mid- to late-sixties, stopping every so often to remind readers that’s he’s getting to the epiphany. On what seems like yet another side trip, Lazar reveals he has an obsession with doo-wop music (The Belmonts, The Four Seasons, The Coasters, The Platters, etc.). He admires how the lead singer’s voice splits between tenor and falsetto or falsetto and bass to convey the lover’s depth of emotion. Equally, he’s charmed by the musicians’ creative use of sound—such as how they repeat nonsensical words—using it for dramatic effect, much the way a writer shifts to italic or breaks into verse.

One example of doo-wop is the song “Lollipop,” first recorded by Ronald and Ruby (Lazar’s preferred version). A catchier, smash-hit was recorded by The Chordettes, known for the finger-in-the-cheek “pop.”

Here, at long last, Lazar loops back to the beginning, approaching the epiphany. He’s in his car, listening to “Lollipop,” and becomes deeply moved, realizing, “a bunch of girls singing about Lollipop were no different than the Tallis Scholars of the Anonymous 4 or Collegium Vocale Ghent. … ” There’s such resonance in this line, readers are likely to feel a jolt. Out of context, without the long buildup and anticipation, it’s impossible to feel it. Here, Lazar shows the journey is just as important—maybe more so—than the destination.

While this essay collection begins somewhat frenetically, it slows at the end. The aphorisms are meant to be savored for their subtle truths, such as this one: “Unless you write your epitaph, you’ll never get the last word.”

I suspect this collection is not Lazar’s last word when it’s comes to essays. However, it’s hard to imagine just what this writer might try next.

Published on January 23, 2018