Innocence

by Michael Joseph Walsh

reviewed by Christos Kalli

Michael Joseph Walsh’s debut poetry collection Innocence begins with an epigraph from the Chinese poet and Tang dynasty politician Du Fu: “the country is broken; the mountains and rivers remain.” From the outset, Walsh goes about exploring the remnants of an ecological, affective, and civil disaster: one that is already underway and also in the making, both inside and outside national boundaries. The collection’s speaker feels, at times, nonhuman—traveling like a drone through what’s “destroying the cared-for air,” contemplating “another creatured life” with the rewired consciousness of a long-dead philosopher, dispensing fragmented images of “the written-on earth” at a machine’s fast pace. While this speaker conjures a sharp critique, the poems of Innocence stay radically optimistic.

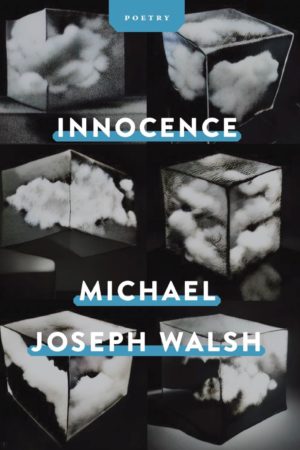

The collection’s critique is embodied by its cover, which shows clouds contained within ice cubes, and continues into the opening poem, “Innocence.” The eponymous quality—once primarily binding womanhood to chastity and childhood to purity—is portrayed here as a label that is meant to performatively defend our actions and absolve us from any responsibility for the environmental crisis:

A volcano of oil is flowing,

and we believe in it,

and call it our innocence.

We admire ourselvesamongst ourselves, not denying

the derisory squeals

into which our avatars

plunge.

It is one thing to passively watch the volcano of oil flowing and another to create a belief system out of that disaster, to deify it. The volcano—which is representative of Walsh’s imagery, charged with political significance by simple diction—erupts with a criticism of those who not only claim innocence, but find self-admiration in that false claim, and have the privilege of avoiding any discussion of consequence. Switching from the first-person singular pronoun—used in this and other poems to signify the positions of the witness (“I will write this as it occurs”) and the visionary prophet (“as the golden / poem ‘I am breathing,’ the moaning of / the I who meets the eye”)—the plural “we” includes the poet in the collective that is both culpable for this calamity and susceptible to its consequences.

Innocence navigates different temporal terrains, which often collapse into each other beautifully. This is the case in “Forecast,” which invokes the familiar definitions of its noun-verb title (the meteorological prediction and the broader prognosis of the future) as well as the ways in which the process of forecasting has changed during this highly mechanized moment of our “world, // this hybrid machine.” The poet asks, and finds it difficult to estimate, what, if anything, we will feel in the future, if we are already “without figure, between oneself” and “with dim dis- / connectedness.” A beam of light interrupts this questioning and provides alternative futures:

The light that spills

through the window is warm,

& crushes this image,

& with a careful humanglance embeds its name in the dark,

then swallows us whole.

What follows from this

expands as a feeling arises:that you will meet me on that ground, or find me

before one order

of feeling folds into its brethren,

fact of that ugly future, sunlight

over the bed with stillness & broken glass.

Enacting a kind of violence against this “dim dis- / connectedness,” like an animal that crushes and swallows its prey, the light restores a sense of humanity and moves us to imagine a future in which a “you” coexists with a “me”—but this vision of companionship and intimacy is unstable. The line breaks, immaculately placed, produce the dread of the unknowable. What happens if you don’t “find me / before one order / of feeling folds”? What is this other, threatening “ugly future” characterized by “stillness” and brokenness?

Despite this sense of instability and threat, Innocence is a collection that insists on renewal, even if it is born of destruction. In the third and final section of the book, the almost fifty-page poem “Wild News” is an epic inversion of the biblical “Good News.” Starting from “the actual beginning,” not the beginning that we have been told, the poem rewrites our story into a sprawling fable that is broadly about relationality:

[ … ] How after fusing

Together the bones of the thingThe house will accept the wind

Into this creatured dream in which we’ll find each otherWell-drawn & alive, real copies

Of those things we remember

The fusing that leads to the feeling of togetherness, the reconciliation of the house with the wind, the unification in the dream, even the use of the ampersand logogram instead of the word “and”: all these elements point to a life in which connections matter. Connections—which are everywhere in the poem, as threads, branches, strings, attachments, networks, and linked edges—are the bedrock in the metaphor of the house. “It is good to find nothing,” the poet writes by the end, “where everything was.”

Readers will find a heap of broken (yet related) images to challenge and intrigue them in Walsh’s debut collection. This allusion to Eliot is not accidental. Walsh writes about his wasteland and its stony rubbish with Eliot’s same intricate, multiscalar vision, often with formal exactness like that of Jorie Graham’s environmental poetry, and with a profound suggestiveness and range that go back to Du Fu himself. Debut poetry collections are not usually this ambitious with what they pursue and how, but when they are ambitious, they are often only that. Innocence is as ambitious as it is carefully crafted, piercing with its emotion and intelligence. This collection’s warnings will make us lose sleep—even as it soothingly turns off the light.

Published on December 6, 2022