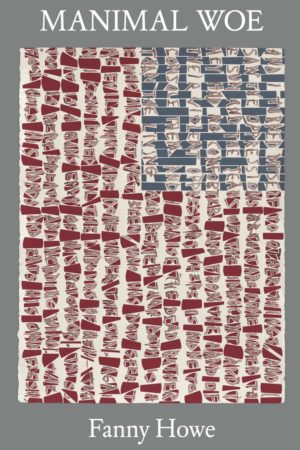

Manimal Woe

by Fanny Howe

reviewed by Jacquelyn Pope

Fanny Howe is a prolific poet, essayist, and memoirist who has become a significant moral voice in contemporary American letters. Her particular attunement to ethical matters is in part an inheritance from her family, which included artists, reformers, and revolutionaries; the events of her lifetime, from the Second World War to McCarthyism, the civil rights and peace movements, and Catholicism, a belief she chose. It also derives from the open steadiness with which she regards and records the world—a continuity of attention that she calls her “staring self.”

Manimal Woe is a meditative homage to Howe’s father, Mark DeWolfe Howe, a civil rights activist, constitutional scholar, and professor of law at Harvard who died in 1967. On the night he died, her father had attended a meeting on busing in Roxbury: “Where he went that night, and what, historically, that time and year meant to the country, was (I see now) weirdly fitting. A person of his time and type would no longer be useful to the movements after 1968.”

The book takes up some of the ideals that shaped Howe’s father and helped form her own convictions, lighting on events large and small, cultural and political, but it proceeds primarily by evoking the personal contours of lived history. Some of her father’s letters to her are included, and Howe’s responses to these and other letters constitute the majority of the book. These are musings, thought-clouds, recapitulations:

Recapitulation is backward thinking, like the composition of a poem or song. You look across a finished thing in order to understand it. You have to go over it again, but include your presence this time. You are now part of the thing you are going over. You can’t ever escape this problem of being where you are as a negative presence. You write facts backwards and forwards and repeat some of it between trying to get yourself out of it. It’s like recycling but reinventing at the same time. In the process of recapitulating, you readjust your impressions of an earlier outcome and shift them a little.

Howe repeatedly invokes the idea of lives and eras, of history itself, being folded over and reemerging with certain elements intact and others disrupted. Some ideas weaken, then spring back into currency with increased vigor. Even when contemporaneous alarms are raised, “plot can only be understood retroactively, and by the time a story is understood, most of the questions that were important earlier have been folded over into another. There is no way to separate the venom of McCarthyism from the coming war against Civil Rights.”

This “folding over” seems only to have intensified in our recent past, making our present both kaleidoscopic and claustrophobic, particularly when considering the junctures at which things might have gone differently. What if a revolution had come to pass? If reformers had prevailed? Howe evokes links between people, eras, and the forces of history in brief sketches of her family and her own life. Her attention is always tuned to connections: “As far as I can tell, things never go away, they fade into financial values: architecture, urban blocks, parks, the arts, especially the banks.”

After her father’s death, Howe goes through his papers. She writes:

It was like trying to do an autopsy on the unconscious, the evidence being what was not revealed. Only the flotsam around it. History. Nature. Voices. In the end I always turn back to the heartbeat of poetry—it’s healthiest when it’s irregular. Having grown up in the atmosphere of politics during the Cold War and real War before that, in the Red Scare, Vietnam, Civil Rights, I could still smell and taste those years and read first-hand the words with their rhythms now slightly foreign.

Manimal Woe is itself irregular, suggesting and swerving where it might have explained. A reader expecting a clear through line will likely be frustrated. Instead, the book illuminates points of connection and friction to produce an account of human resilience, one that has real subversive power in a culture that insists there is “nothing to see here.”

Published on September 9, 2021