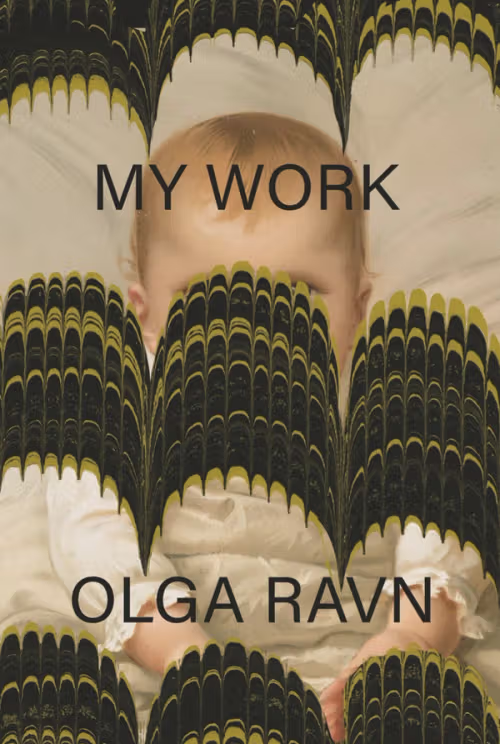

My Work

by Olga Ravn, translated by Sophia Hersi Smith & Jennifer Russell

reviewed by Celine Nguyen

“To live for the sake of art,” reflects Anna, the young mother in Danish writer Olga Ravn’s second novel My Work, “requires a very particular set of life circumstances.” We meet Anna in the later stages of pregnancy and accompany her through a traumatic birth and the first three years of her son’s life. Becoming a mother forces Anna to confront the idealized image of an artist, who would have “Someone else to shop [for her], to change diapers in the morning.” As she puts it, “becoming a mother is unthinkable if one is to become an artist.” What happens to the mothers who refuse this impossible choice—who cling to their literary ambitions alongside their domestic life?

My Work, translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell, is devoted to answering this question. Let’s imagine, Ravn suggests, that this novel wasn’t written by her, but by Anna herself. Ravn is merely arranging her papers. The title, then, might refer to Ravn’s work refining Anna’s experiences into the shape of a novel. It also reminds us of Ravn’s existing reputation as a writer of workplace fiction; her debut novel, The Employees: A Workplace Novel of the 22nd Century, describes a near-future spaceship where human and non-human employees are interviewed about their workplace camaraderie, distress, and eventual insurrection. The setting of My Work—contemporary Denmark and Sweden—is worlds away from that of Ravn’s first novel. But both reflect Ravn’s interest in the tension between waged labor and unwaged care.

The formal experimentation in My Work is striking. Chapter headings announce thirteen beginnings, twenty-eight “continuations,” and nine endings. Each one shifts forward or backward in time, relying on associativity instead of linearity to pull the narrative together. By continually restarting and reentering Anna’s story, Ravn captures all the fury, exhaustion, tenderness, and despair of motherhood. And she uses many forms to do so: third-person narration, multi-page poems, even a miniature play to depict Anna’s group psychotherapy sessions at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen when her postpartum depression becomes intolerable. Anna’s restless, despairing state of mind is conveyed in leaps from form to form:

[S]he kept on breaking the forms, even though it wasn’t destruction she sought, even though all she longed for was a whole …. The forms were old, stiffened, adapted to an outdated reality to the nuclear family, the stay-at-home wife.

Indeed, the novel shows that breaking form is necessary to depicting the most painful parts of being a mother. Anna frets over feelings of maternal inadequacy, her inability to love her son (“something went wrong between them”), and her resentment toward her husband Aksel. Some of the most moving passages describe the alienating experience of realizing how taxing the work of motherhood is compared to that of fatherhood:

[W]hen I did this work—making a child—about which he was clueless, a work no one saw; when I had to lie to him about how his minimal efforts were equal to mine … I understood there was no one with whom to share my innermost feelings. Our paths diverged. And after motherhood, the dream of an absolute romantic love was lost.

This pain is, perhaps, what Ravn herself has experienced. “To write in the third person,” she says, “was to create someone else to endure the pain. One invents her. Her name is Anna.” Through Anna, Ravn can convey the bitterness and disillusionment of motherhood. But she also narrates moments of undiluted happiness, like when Anna lulls her child to sleep and lies by his side, “engulfed by love.” The despair doesn’t cancel out the joy, Ravn insists. At the center of the novel is a scene where Anna and Olga Ravn encounter each other in the text, with Anna mocking her author: “Aren’t you dead yet?

Loving one’s child, My Work suggests, isn’t easy at all. But Anna learns to do so. More than that, she learns to balance the work of motherhood and the work of writing. The novel traces Anna’s return to reading the work of other mothers, from Charlotte Perkins Gilman to the Japanese poet Itō Hiromi, and writing:

I’m writing again. So something inside me must have changed. Is this change for the better? Are my muscles stronger? I’m sitting in the shadowy study. Soon the sun will reach me through the window. And the sun is hot and hard-hitting. I am writing on a mother’s borrowed time.

Through writing, Anna—and Ravn herself—confront the “old, entrenched idea that a woman must choose between child and book … that the child obliterates the book and vice versa.” The novel becomes a way to contain her experiences, cauterize them, and fully inhabit her new life. In one of the final scenes, Anna and Aksel are walking in a park, pushing a stroller. Anna (or is it Olga Ravn?) is pregnant again. Unburdened by the despair of the last few years, unburdened because she is writing, she looks forward to the birth of her second child, to laboring in the delivery room, to the moment when, in the final words of the novel, “my work begins.”

Published on May 7, 2025