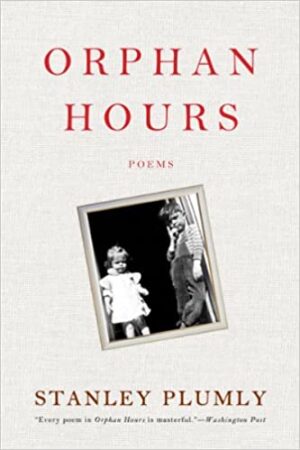

Orphan Hours

by Stanley Plumly

reviewed by Chris Cunningham

The title of Stanley Plumly’s tenth poetry collection comes from Shelley’s “Dirge for the Year,” written New Year’s Day, 1821: “Orphan Hours, the Year is dead, / Come and sigh, come and weep!” But whereas Shelley’s confrontation with death is figurative, Plumly’s is quite real: he announces in the volume’s fifth poem that he has cancer, and mortality is Plumly’s subject throughout—both what it means to die, and, put another way, what it means to live.

Elegy casts a shadow across virtually everything to which Plumly turns his eye: it’s not just that he himself is dying but the world seems emptied of those he loved. Thus the opening poem in the collection ends, echoing Rilke, with a child’s cry of abandonment: “Who will find you, who will call you home now, at dusk . . . ?” (“Lapsed Meadows”). But the poems here aren’t written out of self-pity. On the contrary, Plumly’s attitude toward mortality is clear-eyed, even scientific: his cancer, “this living and immortal thing inside” him, began, like him, as “stardust” (“Cancer”). Indeed, Plumly is a naturalist, remarking constantly the inevitability of endings: “Naturally the sun is falling, which had risen first / light only this morning” (“The Jay”).

Plumly is equally clear-eyed in his rejection of traditional sources of consolation, expressing skepticism about both Christian salvation (“John 20”) and Romantic spirituality (Plumly loves nature, but he senses no intimations of immortality), as well as the secular immortality of literary accomplishment (“My Lawrence”). But a world without heaven can still be hellish, and infernal visions run throughout the collection, especially the end: most literally, Plumly descends into the malebolgia of Dante in his translation of “Canto XVIII,” tormenting himself with the torments of pimps, seducers, and flatterers. In the ekphrastic “Imaginary Prisons,” after Giambattista Piranesi’s surreal prints, Plumly describes an Escher-like space, a chiaroscuro, subterranean city that becomes a female body: “via vulva, vagina, vestibule.” Similarly claustrophobic is “The Sand,” where the poet wanders in a “rain like a sudden jail,” concluding, “I’ll never, where I am, get back to where I started.” But while these poems offer glimpses of Plumly’s internal hells, perhaps the most disturbing of the series is “Human Excrement,” whose nihilistic vision of the physical world—the fact of embodiment—is darker than any dream. After encountering “the odd fragment [of human debris] on the sidewalk,” Plumly is haunted by the spectacle: “this answer to longing / and what is finally left of us.”

This is Plumly at his darkest, and he wrestles with such darkness throughout. Nevertheless, if there is no way to give meaning to death, there are ways to give meaning to life. Quite simply, he suggests that beauty—especially the beauty of the natural world—offers real if ephemeral moments of transcendence. In “Lost Key,” Plumly confronts the fact of unceasing change:

What I saw in the sky each day for a year, for seventy

years, in truth, was never the same, never the same,

not the fixed stars moving in rotation nor the one

moon in its variety. I watched, each fall,

the infinite leaf change and disappear, held it

in my hand, watched it curl, turn to paper,

blow away, never the same, in the same way as words:

to leave, to go or flower, never both at once.

But even as he contemplates a world that is never itself—“never the same”—he transforms the lived present into a moment of grace that redeems his own inevitable fall:

—I like what I think is a sweet Dolcetto,

which stains the sunlight sleeping on the air.

I break the bread seasoned with rosemary. These,

in themselves, miracles.

Light, air, bread, wine: Plumly secularizes the Christian feast into a celebration, not of the world to come, but of the world that is, never to be again. But it is the synthesis of art and memory, the past made present again through poetry, that brings Plumly as close as he will come to redemption: the collection is shot through with Wordsworthian “spots of time,” vividly recalled and recorded moments in which people and things—family members, lovers, friends, strangers on the street—come back to life.

The danger with a poetry of memory is that poems can become mere artifacts of the poet’s own emotional experience (as opposed to the reader’s), as in, for example, “Look for Me,” a somewhat sentimental travelogue of Plumly’s European adventures. A related but different problem surrounds the finally quite moving poems written for Plumly’s ex-wife, Deborah Digges. These are intensely personal poems, almost private, and the reader has to work at times—or be in the know—to share the speaker’s experience. For example, “Afterward,” is a beautiful, haunting poem but only if you know that Digges committed suicide by leaping to her own death.

In a 1995 interview, Plumly rejected the idea that his work, so often concerned with his family, especially his troubled relationship with his father, was “confessional,” suggesting instead that he aspired to the poetic alchemy of turning the personal into the archetypal. At his best, he manages this trick, writing honestly, perceptively, lyrically about his confrontation with his own mortality—the most private and most universal of all human dramas. In the volume’s final poem, “Leavings,” he begins in the unconjugated timelessness of the infinitive, imagining what it means to die:

To walk out of this flesh, leave the body of its bones.

To undress utterly, so that even love and mirrors

and the voice inside your head wouldn’t know you.

To write your name in cold blood by a candle

whose flame would fire air, breath, everything,

including paper. To be totally absent from yourself,

from thought of yourself, to forget yourself entirely.

Without melodrama and with a beauty that gives dignity to becoming nothing, Plumly imagines himself “out of body, out of time, leaving behind, in a wake / of absence, clothes, fingerprints, ashes, words—”

Published on December 2, 2013