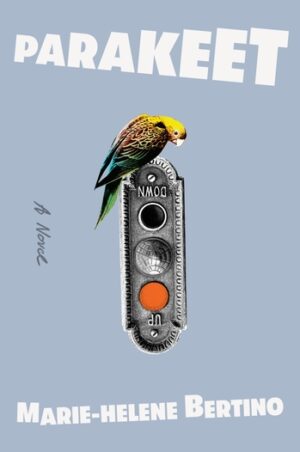

Parakeet

by Marie-Helene Bertino

reviewed by Caroline Tew

Marie-Helene Bertino’s third book, Parakeet, is almost impossible to describe. In some places, the novel is darkly funny, as it points out the ordinary absurdities and hardships of life; in others, it descends into what feels like a fever dream. On the surface, the plot is simple: a woman, known only as the Bride, is about to get married. Her groom is caring, stable, and brings her a sense of normalcy, but she isn’t sure that she loves him. Parakeet follows the Bride in the days leading up to and following the wedding.

But Bertino brings a lot more to the table than a just a love story gone wrong. The novel’s strangeness is apparent from page one, when the Bride sees a parakeet in her hotel room and instantly recognizes it as a manifestation of her dead grandmother. “What is the Internet?” the bird asks. The bird and the Bride discuss the upcoming wedding; the bird is skeptical about the Bride’s compatibility with the groom and insists that she needs to find her estranged brother, Tom. When the bird leaves, the Bride finds that it has defecated all over her wedding dress.

Searching for Tom, the Bride discovers that her sibling is a trans woman who now lives as Simone. Most of the second half of the novel focuses on the rebuilding of the relationship between the Bride and Simone, who had fallen out years earlier. Once reunited, the sisters begin to make sense of their connection to one another and to their difficult mother. The quiet conversations they have together, rather than the Bride’s catastrophic wedding or the surreal events surrounding it, turn out to be the novel’s heart.

Along the way, however, we encounter some truly bizarre misunderstandings. One morning the Bride becomes convinced that she is inhabiting the body of her mother. She also thinks that the woman who sells her a wedding dress looks exactly like her. There are strained conversations and strange fart jokes, and too often the novel’s weirdness has no discernible purpose, seeming only to distract from the story’s emotional force.

More effective are the novel’s funny one-liners. These aren’t always jokes but rather moments of levity when the characters are most stressed. “Dear god, the ass. Inherited from my grandmother, that immortal spread,” laments the Bride. Bertino tends to poke fun at the inelegance of middle age and social oddities that are often overlooked or taken for granted. These moments help to lighten a novel that fundamentally deals with terrorism, identity, and dysfunctional family relationships.

The best parts of the novel are the occasional poignant moments. “Have you ever missed someone so much that the missing gains form, becomes an extra thing welded to you, like a cumbersome limb you must carry?” the Bride asks her parakeet-grandmother, thinking of Simone. The parakeet’s response is dismissive—“Dramatic,” she says dryly—but the novel does not dismiss the Bride’s pain. Bertino’s understated portrayal of the difficult parts of life are what make the book worth reading, despite the many distracting tangents of body swapping and misidentification.

Each of the novel’s final chapters wraps up one of the story lines: the Bride’s relationships with the groom, her mother, her sister, and her dead grandmother. Though touching, these chapters feel like serial attempts at a perfect ending rather than a cohesive finale, reflecting the novel’s scattered attention.

Published on December 29, 2020