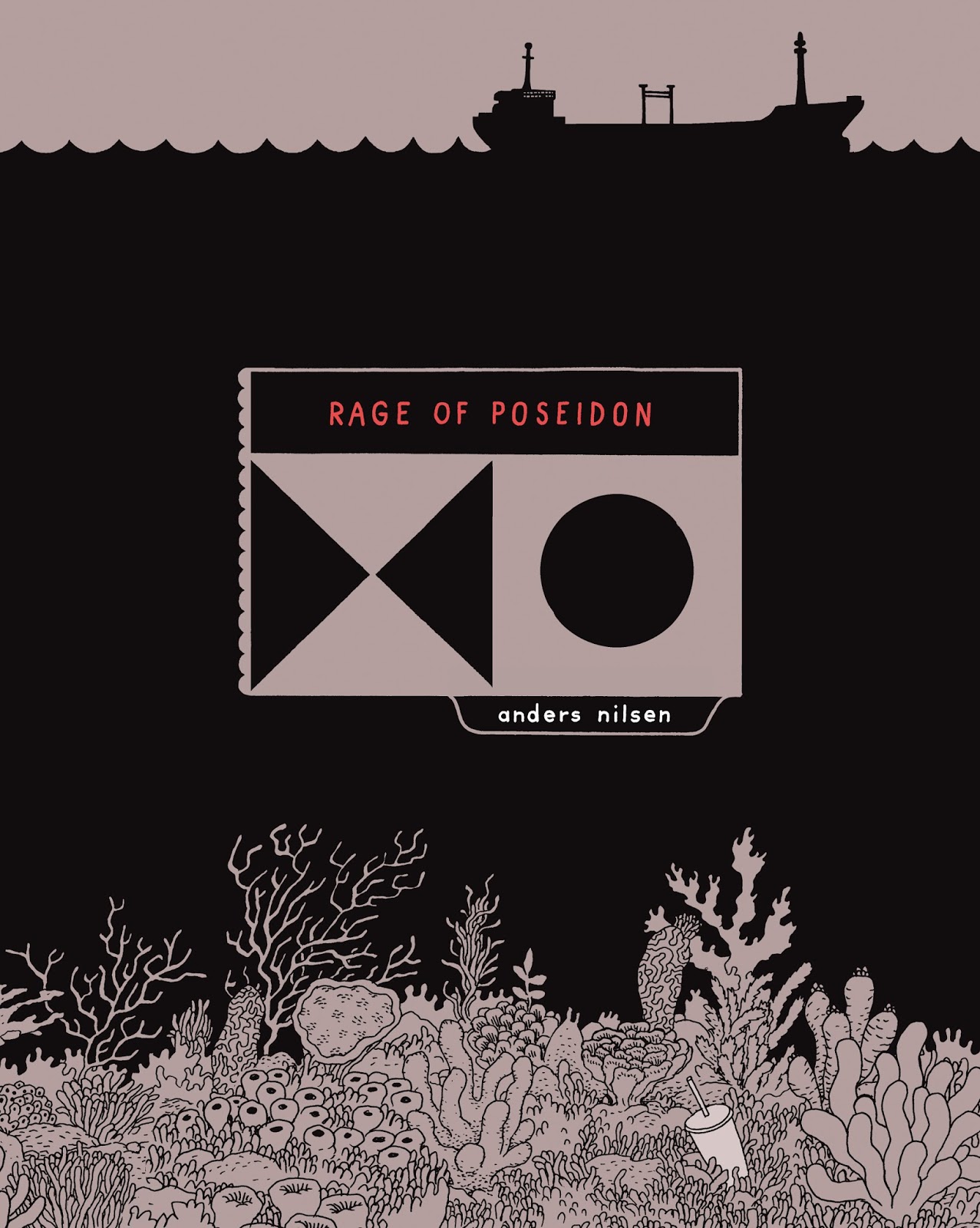

Rage of Poseidon

by Anders Nilsen

reviewed by Paul Hanna

Combining and contrasting the mundanity and tragedy of human existence with the divinity and cruelty of mythical gods is not an altogether new idea in comics, much less in literature. Eddie Campbell’s Bacchus follows the eponymous Greek god in a contemporary setting. Even Thor from Marvel Comics brushes upon some of the same ideas, albeit very occasionally and with the earnest, hyperbolic, and lighthearted flavor that can only come from superhero comics of the early 1960s. Now, Anders Nilsen uses the gods-among-us approach to raise questions about humanity and its existence in Rage of Poseidon, rethinking ancient myths for the modern era.

A collection of short, mythical tales retold in a contemporary setting, Rage of Poseidon follows classic Greek and Roman gods and Judeo-Christian icons as they explore questions about the mundanity and tragedy surrounding human life, usually by acting like typical, confused, vindictive, sensitive, and/or self-destructive humans who happen to be immortal.

More than the content, however, the form is what delivers Rage of Poseidon into noteworthiness. The entire book unfurls like an accordion, each fold showing a single silhouetted image captioned with a piece of story. While this allows the reader to look at many images at once, the book itself is, when fully unfurled, like an object that exists at the nexus of an art gallery and a ruined wall or scroll inscribed with ancient glyphs. Some of the silhouettes are abstract, though most are unmistakably concrete. This is where the essence of the book’s narrative lies; comics excel at simplifying the visually complex, evoking iconic meaning and symbolism using images, and the criteria of gods and myth are ones well-suited to such evocation.

This visual approach to storytelling allows Nilsen to not only highlight the humanity within tales of ancient myth, but he is also able to touch upon some of its inherent ridiculousness. By bringing these mythic figures into more modern trappings, they become more believable and easier to accept; their flaws and foibles also become much more pronounced.

The stories shift narrative modes from tale to tale. Most stories use the second person, but “Leda and the Swan” is told in the first person (from Zeus’s perspective), while “The Flood” is told in the third person (from inside a juvenile God’s bedroom). The narrative modes create a sense of mystery, just as the stark silhouettes do. While the reader never actually sees the faces of the silhouetted figures, the source of the narrative voice also remains a mystery. Ultimately, it does not matter who is actually addressing the reader as “you,” what’s important is that it adds to the mystery of the myth and adds a suggestive layer of absurdist ambiguity. Still, the shift to the first person in “Leda and the Swan” is unambiguous, where Zeus (“I”) directly addresses Leda (“You”). A greater implication about the narration also exists, as this first-person tale wedged in between two second-person narratives in the book. Perhaps Zeus is the mysterious narrator? The question is plainly there for the reader to think about, but it does not seem to make a difference within the greater context of the book.

In the tale of “The Flood,” the shift to an omniscient third person narrative mode creates a wry and bizarrely appropriate juxtaposition with an “omnsicient” God who comes off as juvenile, regretful (“I didn’t mean to kill them all! Now they’ll really hate me!”), and insecure. While this juxtaposition might have been communicated more directly with a shift to another scene, such as Noah on the Ark, the tale obviously aspires to be something closer to a vignette than a longer short story.

Nilsen’s writing is neither wordy nor ponderous; his direct language is sincere without being pedestrian, and the stark black-and-white, silhouetted imagery makes everything in Nilsen’s world iconic and important, while still elegantly placing each tale within its own blended mythical and modern setting. Even the most mundane and grounded places manage to visually evoke a sense of myth: Abraham’s living room, Venus’s kitchen, and a water amusement park visited by Poseidon.

As these are retellings of existing myths, it is hardly unexpected to say most of these tales end in tragedy, but none are without a darkly comedic lining. It is also arguable that the tragedy of the original myths are simply exchanged for a dark comedy in Nilsen’s reimaginings. Rage of Poseidon is a loving, quirky appreciation of myth and a subtle satire of religion and religious belief.

Published on March 25, 2015