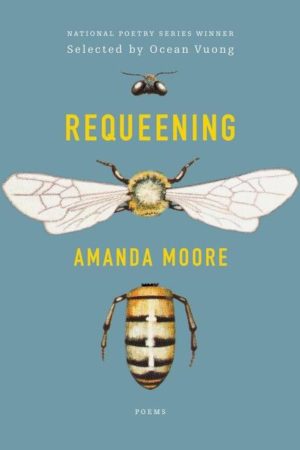

Requeening

by Amanda Moore

reviewed by Jeffrey Careyva

Requeening is Amanda Moore’s debut book of poems, and between lyrics to dead animals and ruminations on Homer’s Odyssey, there’s a lot to be buzzing about.

The book’s title refers to the act of replacing a beehive’s queen with a new one, and for Moore this is both a literal and figurative undertaking. Requeening is definitely about honeybees, those strange and productive creatures without whom whole crops and ecosystems would collapse, but it’s also about sticky and barbed human relationships. Tending to the beehive is an occasion for illuminating the interdependent, precarious, and doting bonds that connect mother and daughter, husband and wife, and even the poet to her material. As its own flight of the bumblebee, Requeening takes us on multiple odysseys: from birth to adulthood, bloom to collapse, beloved home to beloved home, and diagnosis to remission.

The first poem of the collection is aptly entitled “Opening the Hive.” Right from the start, Moore lodges speculations about her own origins in the hive’s honeycomb:

Late afternoon slants, illuminates

the worn, white husk of hive and gleams

like an incubator bulb on the oval of an egg.

This might have been the way I was born

to move over my mother and wash from her

what was left of painful birth, her legs

like the old wood cracked with a hive tool,

my lips clamping and the bees burrowing

into honeycomb, bathed in sweetness,

a taste fresher when robbed this way.

With its allusion to Emily Dickinson’s “There’s a certain Slant of light,” the opening verse paragraph establishes the intricate layering of metaphor that lends these poems emotional weight. The mother is both shelter and progenitrix; the beehive is a “small universe” that hints at the gravity of the solar system formed by mother and child. The scale of poems like “Opening the Hive” frequently shifts, as the bees’ social organization prompts us to think not just about the individual worker, but also the entire hive; not just the newborn daughter, but also the matrilineage that nurtures her.

Moore consistently grounds the reader’s imagination in details from her and other creatures’ shared lives. There are wasps in the walls, a rotting animal in the ducts, vitamins in the medicine cabinet. Moore’s interests lie in the everyday, though she manages to invest the everyday with a sinister transitoriness. The beehive might be most closely associated with honey, but Moore doesn’t let us forget about bees’ notorious ability to sting and lay down their lives. As Moore shares poems about moving to a new house or dealing with a broken leg in the family, it’s hard to miss her remarkable attention to the frailty of all things. The ominously entitled “Collapse” says it most succinctly: “Our bodies are built to decay.” (In “Afterswarm,” the beloved bees abandon their hive.) Death and life are intertwined in these poems, as they are in any ecosystem, or in the story of any family.

Moore writes most of her poems in a balanced style of free verse, but there are plenty of forays into regular stanzaic patterns and traditional forms: elegy, aubade, even a “Sonnet While Killing a Chicken.” “Waggle Dance” features inventive line breaks and indentations suggestive of bees’ own animated form of communication. The latter half of Requeening includes a series of haibuns—prose poems that culminate in a haiku—recounting the joys and travails of parenting a teenaged daughter. The prose sections capture all the little details, while the concluding haikus frame the mother-daughter dynamic as a small part of the larger natural world.

While Moore takes full advantage of past poetic traditions, she is not beholden to them. Bees in traditional poetry are often social but also militaristic—Homer’s comparison of the Achaeans to swarming bees in the Iliad, say, or Virgil’s bees in the Georgics, which resemble the Roman imperial state. Moore’s bees, and her own sensibilities, incline less toward politics and more toward private relationships built on mutual care.

Moore does, however, interact with classical epic in a way that updates the genre for the present. In “After the Phone Call I Teach Book 11,” Moore’s quatrains relate the experience of teaching the Odyssey in the midst of her own health crisis:

You’re Odysseus, or you’re dead:

some forgotten bit of flotsam

left to die along the way. Fate

is absolute, and I’ve taught this book so longthere is no other way to hear

the news on the phone

when the doctor calls before class

with biopsy results.My 9th graders file into our room

and I am at the whim of divine irony:

my mortality unspooling

just as I have to teach a lessonon Odysseus’s journey to the Underworld

where he hears true suffering

isn’t the moment of death

but the endless afterlife.

As any teacher might, Moore soldiers on with a lesson whose seriousness isn’t lost on her students or her readers. Moore’s metaphors and references subtly shift as Requeening progresses. The hive is a place of birth and also a home that requires upkeep; the body creates life while also consuming itself. There are worlds within Moore’s words—some, like the hive and the underworld, daring you to open them.

Published on December 21, 2021