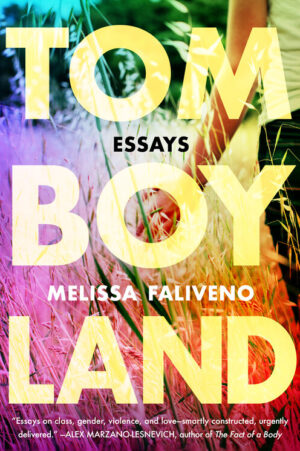

Tomboyland

by Melissa Faliveno

reviewed by Ben McCormick

The question “where are you from?” is seldom really about geography, and for Melissa Faliveno, answering “Wisconsin” just doesn’t cut it. Faliveno’s debut essay collection Tomboyland makes visible a Midwest region that was considered “flyover country” before the 2016 election and became subject to all manner of sweeping generalizations after it. Across eight essays, Faliveno expertly braids memories of her upbringing with interviews and research to render Wisconsin a living, breathing thing. She accounts for the centuries and decades before her birth, her formative years, and the years since she left for New York. Some Midwestern stereotypes hold true—politeness really is like oxygen, and religion is a form of protection—but in 2020, BDSM scenes, polyamory, vegetarian diets, and queer culture are Midwestern, too. Faliveno knows she has caught her subject in the middle of a breath. With a characteristic generosity, the essays of Tomboyland look back on the Midwest’s complicated past and forward to an optimistic future.

The first essay, “Barneveld,” opens with a passage from the Book of Hebrews and then tells the story of an 1984 F5 tornado that leveled the titular town, injuring hundreds and killing nine. The tornado looms biblically large, at once an engineer of tragedy and a natural marvel. Using interviews with a web of family members who lived in the area, and eventually a woman whose young son was killed, Faliveno makes the pain of the past hauntingly present. She recreates that June day: “They will remember when the clouds begin to build, when they billow and hum […] They will remember when the air becomes so thick and electric they can feel it in their teeth.” The wonder in this description asks a vital question, at the heart of the contact between Faliveno’s queer identity and her home state’s traditionally conservative values: how can something so harmful be so lovely?

Luckily, this in-between is where Faliveno is most comfortable. In “Tomboy,” she writes about her discomfort with her feminine name, and never fully condemns or accepts it. This willingness to sit with difficult questions and recognize the self as variable echoes across the whole book, perhaps never more explicitly than when she writes, in “Gun Country,” that “it’s a question, like so many, I’m still trying to figure out.” Faliveno’s is a refreshing disposition that goes beyond the personal-essay standard of concluding on a fixed ambiguity to admitting that if she were writing this essay on a different day, its conclusions would probably change. Her comfort with considering the self openly inhabits the pair of essays at Tomboyland’s heart, “Switch Hitter” and “Meat and Potatoes,” in which she explores sexual attraction and BDSM with triumphant confidence.

“Meat and Potatoes” embodies a battle that anyone who’s left their hometown can understand—between knowing your home is flawed and feeling an inexplicable, bone-deep love for it anyway. In this essay, Faliveno considers her distaste for meat and simultaneous appreciation of its source, then turns to the parallel feeling of how pain brought by BDSM transforms into pleasure. She goes from sensuous prose in one paragraph—“Lost in the rhythm of a whip, I felt the sting subside—first a sharpness and then a smoothing out. It melted into a kind of deep, corporeal buzzing”—to more cerebral prose in the next: “At first, masochism seemed at odds with my budding identification as a feminist.” It’s a potent, enthralling tension, and Faliveno pits them against each other again and again, funneling down until we feel there couldn’t possibly be a reconciliation, and then she pulls the reader back to the surface—to the the essay’s opening images—for fresh air.

Faliveno’s voice is charming, and most so in the moments that exhibit traditional Midwestern culture without recognizing it. She’s often the kind of “Midwest nice” that refuses to confront a viewpoint directly, but pressures it endlessly to see if it’ll give way. She delivers a series of “Forgive me … ” apologies in “Switch Hitter,” and she ends each essay on an optimistic note that makes a reader wish for a friend like her. Her use of the term “Midwestern,” though, sometimes works against the book’s goals of nuanced visibility—referring to the region stretching from Missouri up to Wisconsin and over to Ohio as a monolith diminishes the complexity of its characterization. It may be a rhetorical strategy; she often reserves the word “Midwest” for marking traditional truisms, and lets the younger, more progressive characters in her life highlight the region’s transformation-in-progress. It may also reflect Faliveno’s generous persona, a well-intended attempt at inclusivity. But just like the intentions of the elderly generations she interviews, the decision to use the general term “Midwestern” is both wholesome and imperfect.

Tomboyland is a strong, vulnerable debut. Melisssa Faliveno hones a singular style of interlinked optimism in her essays, which paint Wisconsin as a place of immense, ancient histories and a place with hopes for great change in a shifting world. Her writing would make a native to the region proud of its complexity. In “Motherland,” she writes: “We return to our motherland. And if we are good, we give back to her. We tend to her, care for her, in the way she once did us—because we know that someday she will be gone.” Yes, this is a lament that in the face of social upheaval the solid place Faliveno called home will perish. It is also a wish.

Published on October 27, 2020