When Tarzan Met Leonardo

by David Rompf

In the midst of the Great Depression, the ten-year-old son of an Express Railway agent hunkered down in his modest family abode in Anderson, South Carolina, to read the Tarzan novels. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan, unlike the character depicted in the movies, is cultured, literate, and worldly, and he quickly masters French, Finnish, Dutch, German, Swahili, Mayan, Arabic, ancient Greek and Latin.

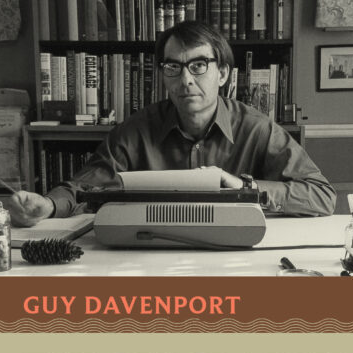

The boy in Anderson—his name was Guy Davenport—might have seen Tarzan as a model for his own development as a polymath. He found another role model at thirteen, when he devoured a biography of Leonardo da Vinci. Like Leonardo, Davenport had an aptitude for drawing; eventually he illustrated stories of his own. Like Tarzan, his linguistic ability was agile and expansive. He abandoned Anderson’s Boys High School in the tenth grade to attend Duke, where he studied classics and English literature and embarked upon an illustrious academic career. He won a Rhodes scholarship, read Old English under J.R.R. Tolkien and wrote the first thesis on James Joyce to be accepted and published by Oxford University. After two years in the army and a teaching stint at Washington University, he earned a Ph.D. in literature at Harvard, completing a dissertation on The Cantos by Ezra Pound. Davenport the boy became a man of many talents: illustrator, translator, professor, critic, poet, essayist, and fiction writer who produced more than thirty books, including The Geography of the Imagination, a collection of forty essays originally published in 1981 and recently reissued in a handsome edition by Godine Press, nearly twenty years after his death.

The title of the book could be “The Geography of Guy Davenport’s Imagination,” for it is, ultimately, a window into the boundless landscape of the author’s mind. The book offers sweeping vistas in its analysis and commentary on art, literature, and aesthetics, and on many of the giants—and underappreciated figures—in those realms. Individually and collectively, the essays cohere. They are tied together by their breathtaking perspective and intellectual rigor, and perhaps most of all by Davenport’s passionate conviction, which is untinged by cockiness. They are substantial, learned, and downright thrilling.

Cynthia Ozick once declared, “The essay is not meant for barricades; it is a stroll through someone’s mazy mind.” If there is information in an essay, she argued, it is incidental, and if there is opinion, we don’t need to buy it. “A genuine essay rarely has an educational, polemical, or sociopolitical use; it is the movement of a free mind at play.” Davenport, a barricade-buster, seeks to dismantle any conventional wisdom that has plagued works of art and literature—and their creators—and stymied a deeper understanding of them. From prehistoric art to Walt Whitman, James Joyce, Louis Agassiz and beyond, he seeks to set the record straight with crucial clarifications.

Davenport’s approach to essay-writing, in other words, often seems inherently polemical and unabashedly educational. He wants the world to change its mind, and he wants to teach us: after all, he was a professor at the University of Kentucky for nearly thirty years and a lifelong evangelist of aesthetics. (“Art is the attention we pay to the world,” he writes in a magnificent examination of Eudora Welty.) This compendium fulfills his mission of demolishing conceptual and ideological barriers—the information contained in its pages is indispensable and invariably fascinating.

Each essay in The Geography of the Imagination is more obstacle course than maze, and we are prodded to pick up the pace, from a stroll to a sprint, in making connections across epochs and continents. These essays leap across periods with prowess, and reading them seems like a form of time travel. Davenport is a Leonardo and a Tarzan, as even one of his footnotes suggests: “Someone must someday write about the affinity between steamboats and poets.” His dexterity in mining widely dispersed, occasionally arcane reference points and expounding fresh insights is humbling. Googlers, on your mark. Readers of every ilk, buckle up: research and reacquaintance are needed to complete this course.

What is a geography of the imagination? The eponymous first essay serves as an overture for the subsequent thirty-nine essays explicitly or implicitly tethered to the concept. After reading the piece, you have a sense of where he’s going, although it’s best not to get too comfortable: detours should be expected. “The imagination; that is, the way we shape and use the world, indeed the way we see the world, has geographical boundaries like islands, continents, and countries,” Davenport writes. He traverses these porous geographic, cultural and temporal boundaries. When Davenport looks closely, he sees that the first Thoreau was named Diogenes and Edgar Lee Masters’s 1915 Spoon River Anthology was first written in Alexandria. “A geography of the imagination,” he writes, “would extend the shores of the Mediterranean to Iowa.”

The reference to Iowa isn’t random. As always, Davenport has a talent for nifty narrative springboard. Eldon, Iowa, is where Grant Wood began working on American Gothic. Davenport’s dazzling analysis of the painting shows the geography of the imagination in action as he parses the influences behind Wood’s masterpiece, leaving no brushstroke unexamined. There are seven trees, he points out, the same number of trees along the porch of Solomon’s temple, symbols of prudence and wisdom. “The bamboo sunscreen—out of China by way of Sears Roebuck—that rolls up a like a sail: nautical technology applied to the prairie.” And: “The sash-windows are European in origin, their glass panes from Venetian technology as perfected by the English, a luxury that was a marvel of the eighteenth century, and now as common as the farmer’s spectacles, another evolution in technology that would have seemed a miracle to previous ages.” He doesn’t stop there. We learn of the thirteenth-century inventors of eyeglasses as well as the first portrait of a person wearing them, a 1352 fresco by Tommaso da Modena. “We might note, as we are trying to see the geographical focus that this painting gathers together, that the center for lens grinding from which eyeglasses diffused to the rest of civilization was the same part of Holland from which the style of the painting itself derives.”

On and on he writes, with staggering, meticulous precision. He maps the cultural and geographic pedigrees of the window curtains, the apron, the bib overalls (designed originally in Europe and manufactured in America for JCPenney, using denim cloth from Nîmes), the buttonholes in the clothing, the farm wife’s hairdo, her cameo brooch, her step behind her husband. The couple’s formal pose “lasts 3,000 years of Egyptian history, passes to some of the classical cultures—Etruscan couples in terra cotta, for instance—but does not attract Greece and Rome. It recommences in northern Europe where (to the dismay of Romans) Gaulish wives rode besides their husbands in the war chariot.” Exhaustive but not exhausting, Davenport is blessed with a fiction writer’s gift for storytelling, and he uses it shrewdly, in generous doses, to avoid the ponderousness of criticism. In the same essay, an equally scrupulous approach is applied to Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Philosophy of Furniture,” a treatise on how rooms should be decorated, from which Davenport teases gothic, arabesque and classical influences—or, as he puts it, vocabularies of imagery. “If you follow the metamorphosis of these images through all of Poe,” we are advised, “you would discover an articulate grammar of symbols, a new, as yet unread Poe.”

Davenport is, to state it mildly, obsessed with the influence of the archaic on the modern, and modernity’s aesthetic debt to the archaic. “Prehistory is one of my madnesses,” he once wrote in a letter to a friend. “The Symbol of the Archaic” is an anchoring essay for that madness. We learn of an ox rib found in 1970 in the Dordogne. Between 100,000 and 200,000 years old, the bone was engraved with seventy lines and might be the world’s oldest known work of art, Davenport says. Alternatively, it might be a “tax receipt, a star map, or whatever it is.” We’ll never know for sure, but the existential questions he raises are captivating. Then, at breakneck speed, we skip over millennia to the day when Picasso crawled into the Cave of Altamira and observed the pictures of bulls painted on the ceiling. “What is most modern in our time frequently turns out to be the most archaic.” The archaic, he claims, is one of the great inventions of the twentieth century, and the passion for the archaic is a “longing for something lost, for energies, values, and certainties unwisely abandoned by the industrial age.” As Picasso liked to say, modern art is what we have kept.

“Primitivism” has too negative a ring to Davenport’s ear; “reinvention” or “reappearance” might be more apt descriptors for the persistence of the archaic into the present. Brancusi, Giacometti, Miró, Klee, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, Martha Graham, Jean-Paul Basquiat: Why have artists reached for archaic symbols to interpret the distress of mind and soul? One reason Davenport suggests: the radical change in our sense of what is alive and what isn’t. “We have recovered in anthropology and archaeology the truth that primitive man lives in a world totally alive, a world in which one talks to bears and reindeer, like the Laplanders, or to Coyote, the sun and moon, like the plains Indians.” In a smack against modern progress, he argues that “science began to explain the mechanics of everything and the nature of nothing.”

His obsession continues in “Prehistoric Eyes,” an ardent call to understand the vocabulary and grammar of cave paintings. There’s a nagging problem with relatively modern humans attempting to interpret the cave paintings, he tells us, and that problem is one of context: How did those images figure in the lives of our ancestors? His consideration of prehistoric cave drawings leads him to make a provocative argument: Art has not evolved; modern artists have learned more from the archaic than from recent centuries. “Man, it would seem, does not evolve; he accumulates.”

Wait, not so fast! the reader is tempted to reply. Digital technology has revolutionized art and in life! Language continually evolves—Oxford’s most recent word-of-the year is rizz—but we can hear Davenport quibbling that linguistic development involves, to a large extent, one language accumulating bits and bobs, changing sounds, acquiring new usages and meanings here and there. A case in point would be Japanese, composed of three writing systems: kanji, the characters acquired from Chinese, by way of the Korean Peninsula; the katakana alphabet used for expressions borrowed from English and other foreign languages, and hiragana for words that were originally Japanese. A geography of the imagination, Davenport might say, necessarily includes a geography of linguistics.

Ezra Pound shows up everywhere in these essays. His name is mentioned 273 times, or about once every other page. His presence manifests as the preeminent poetic genius of the twentieth century and, probably because Davenport knew him personally, as Pound the flawed, quirky, controversial man. “Ezra Pound 1885 – 1972,” a eulogy, begins with an elaborate description of Pound’s coffin being transported by gondola through the canals of Venice to a temporary grave at Campo Santo. The passage itself is dirge-like. “His generation has assumed that a life was a work of art,” Davenport writes of Pound. And later: “He was a renaissance.” The most personal and I-centric piece among the forty, it stops short of wistful reflection. We learn that Davenport first read The Cantos years before meeting Pound, during a walking tour of Italy and France in the company of Christopher Middleton, and he admits that he had hardly any notion as to what the poem was about, “except that it had strangeness and beauty in great measure.” That reading prompted him to learn Italian and Provençal, and to paint in “the quattrocento manner.” During his visits with Pound at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, he witnessed the poet’s antisemitism up close, deeming it wacky, though he also says that southerners “take a certain amount of unhinged reality for granted.” That comment seems tone-deaf coming from someone who lived and taught in the Jim Crow South. Ironic, too, in light of his declaration several paragraphs earlier: “Nothing characterizes the twentieth century more than its inability to pay attention to anything for more than a week. Pound spent the last third of his life learning that the spirit of the century was incoherence. Men who forget the past are doomed to repeat it, and the century has idiotically stumbled along repeating itself, its wars, its styles in the arts, its epidemic of unreason.”

In an adoring review of Hugh Kenner’s study of Pound, Davenport asserts that the poet was the first to arrive in the modern renaissance “and his reputation will be the last to arrive in its proper place in the world’s opinion.” Pound’s sixty years of literary productivity, he maintains, can be encapsulated by one phrase: to find the best in the past and pass it on. In this respect, Pound is his model for a geography of the imagination. When this collection was first published in 1981, Hilton Kramer, then the chief art critic for The New York Times, wrote in a review that Pound was the volume’s “principal shaping spirit.” But while the poet’s influence is clear and undeniable, the force that brings each of these essays into being surges first and foremost from Davenport’s exuberant romance with the past.

So many excellent, gripping essays are bound together here. A beautiful tribute to Walt Whitman might be one of the most moving assessments I’ve yet encountered about the poet: “He talks to us face to face, so that our choice is between listening and turning away. And in turning away there is the uneasy feeling that we are turning our backs on the very stars and ourselves.” Davenport refers to Whitman, rightly, as risky currency; it was easier—less controversial—to embrace Thoreau or Emerson. He suggests that a proper understanding of him, and particularly his espousal of erotic camaraderie, calls for, once again, reaching back to the ancient. In his love for handsome boys, Whitman was “reinventing a social bond that had been in civilization from the beginning, that had, in Christian Europe, earned various dodges, and met its doom in Puritanism and was thus not in the cultural package unloaded on Plymouth Rock.”

In “Joyce’s Forest of Symbols,” we get nothing less than an eye-popping reeducation on Ulysses. “You do not read Ulysses,” he instructs. “You mouth the words.” It would be a disservice to summarize his most enlightening observations about the novel—his expository method itself is riveting, and the revelations startling—but suffice it to say that Davenport will make you want to reread the book, read it for the first time, or finish it after decades of neglect. Meanwhile, a paean to scientist and eugenicist Louis Agassiz—like Davenport’s tribute to Pound, this one has dated—nonetheless provides a rousing defense of scientific writing as literature. Agassiz never got around to believing in evolution, but no matter. Davenport regarded the verbal precision of Agassiz’s prose “unmatched in American literature”; Darwin’s writing, by contrast, was wordy and undistinguished. Whether or not we agree, his critique of two giants in science once again reveals that his curiosity is unhindered by disciplinary walls and notions of expertise.

In typical criticism—academic essays or garden-variety book reviews—humor is a rarity, perhaps for good reason. It’s not easy to be funny on paper. Critics fear not being taken seriously, and no stable of role models exists: universities can’t teach something that is essentially unteachable, and they don’t encourage it, either. But there is nothing typical about Davenport, a literary writer who can seem, at times, the slightly pugnacious bad boy of academia dressed as a southern gentleman. He can be slyly droll or overtly hilarious at unexpected moments, with pinches of Oscar Wilde and Dorothy Parker, but hardly anyone who has written about Davenport seems to have noticed that. Or if they have, they’ve been unwilling or unable to give his comic streak due consideration. “One suspects that Thoreau could have married a woodchuck or a raccoon,” he writes, “if the biology of the union could have been arranged.” On meeting James Joyce five times: “Four times we said, ‘Please to meet you.’” He scolds The New York Times for not including a biography of Charles Ives on its list of notable books of 1974, “an oversight comparable to omitting Lincoln from a list of Presidents.” He also recounts visiting the composer’s birthplace. “Naturally the site is now a parking lot; naturally the parking lot is owned by a bank.” He relishes relaying a story about meeting Jean-Paul Sartre at Les Deux Magots in Paris: the philosopher’s jacket caught fire by a lit pipe inexplicably lodged in his pocket.

The levity, which can be trenchant, peaks in “Poetry’s Golden,” a short, punchy account of Poetry magazine’s fiftieth anniversary celebration as part of the First National Poetry Festival held at the Library of Congress. Though he’s an invited guest, Davenport sounds like a journalist who, in a wink-wink dereliction of duty, offers a sendup of cultural reportage. Think of it as a high-minded version of Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update.” “One began to see that panel discussions will go down in history as one of the characteristic aberrations of our age, as peculiar to us as bulls leaping to Cnossans,” he writes. Davenport characterizes the festival by naming all the important poets who are absent from the event, which “raged for three days.” Karl Shapiro, he reports, recommended euthanasia for American poetry. Elsewhere in the collection, he refers to the “blue-haired followers of Kahlil Gibran.”

Off the page, too, Davenport was skilled in waggish repartee. In an interview with The Paris Review, conducted by John Jeremiah Sullivan, who wrote the foreword to this new edition of The Geography of The Imagination, he commented on a reader who was surprised to find happy characters in his stories. “I think it’s taboo to write about any kind of happiness,” he said. “I mean, Joyce Carol Oates would burn her typewriter if she accidentally wrote about some happy people.” The wit, the wisecracks, the light-hearted but telling anecdotes, wherever they appear, exert more than a counterbalancing entertainment. While we can imagine Davenport grinning at his own barbs, his purpose seems large and benevolent. “The comic spirit is forgiving,” he writes. Even in criticism, he suggests, we must remember that life, as Wilde said, is too important to be taken seriously.

Davenport was a visionary humanist who could hook the present to the deep past and unearth an ingenious understanding of subjects spanning disciplines. (One of his courses at the University of Kentucky was called “Literature, painting, film, philosophy, architecture.”) Engaging with the labyrinth of his vast imagination is always a pleasure. Genius that he was, he recoiled from suggestions that his writing reflected overrefined braininess. In a 1979 letter to a friend, he wrote, “How can I shake this reputation of being an ‘erudite’ writer? I’m about as erudite as a traffic cop. I like to know things; what’s so two-headed peculiar about that?” Despite the false modesty, his essays sing with erudition, but they are never stuffy or pretentious. A syllabus for a lifetime of reading could be gleaned from them.

In an interview with Conjunction magazine in 1995, Davenport was asked how he would situate himself in American literature. “As a minor prose stylist,” he answered. “I am a minor writer because I deal in mere frissons and adventitious insights, and with things peripheral. Very few people are interested in what Greek antiquity looked like to a traveler or what airplanes looked like to Kafka.” When it comes to their professional identities, and assessing their own output, writers can be fussily self-deprecating. Davenport, apparently, was no different. But he has grossly underestimated his style, which avoids academese altogether. Throughout these essays, he demonstrates a flair for catchy, aphoristic sentences, many of which seem to echo Emerson or Thoreau. (“Art is always the replacement of indifference by attention.” “Literature is now a river in an ocean.”) From fiction he learned the importance of good stories well told, and he knows how to weave them into his essays at just the right time—usually in the beginning, to lure us in, the perfect anecdote grounding us before a cascade of stunning analytical scrutiny cracks our minds open.

After a diagnosis of lung cancer, Davenport gave up most writing except for his correspondence with friends. Reading The Geography of the Imagination forty-three years after its first publication, it’s intriguing to wonder what Davenport would have thought about the impact of artificial intelligence on the arts, about non-fungible tokens, the resurgence of flash fiction, the traveling exhibition called “Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience,” and Everything Everywhere All At Once. The only disappointment is that he died too soon to say.

Published on May 23, 2024