Cambridge

by Patricia Vigderman

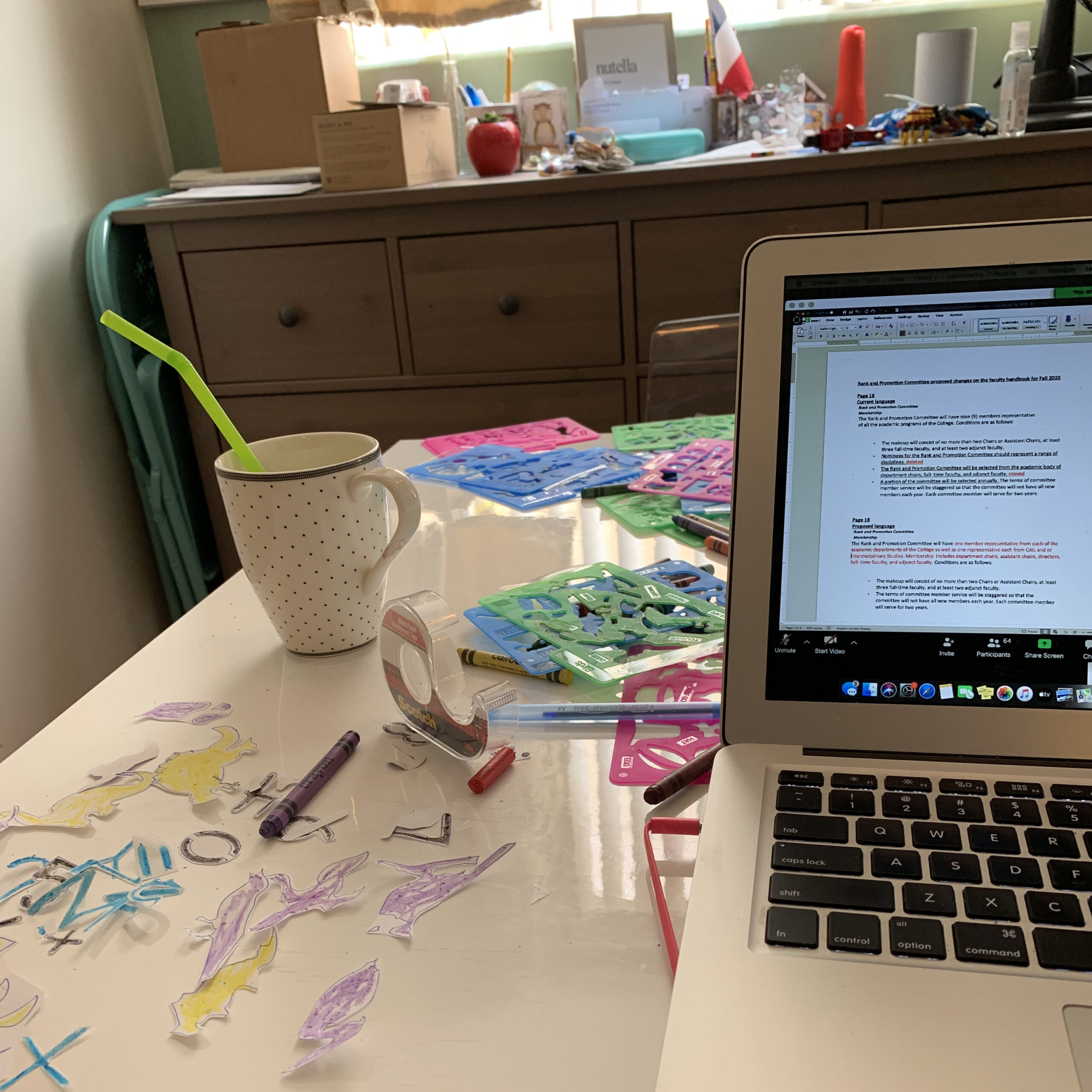

Masked bandits all, we walk the streets of our neighborhood as the spring arrives in its oblivious splendor. We are grateful indeed for the freedom to be outside, and for the newfound intimacy with strangers, as we step into the nearly traffic-free streets to avoid coming too close to them. Muffled to the eyes, we wave, smiling invisibly. Last week the groceries were delivered by a young fellow also invisible behind his mask, hands in his disposable gloves moving so fast among the bags of food he hardly paused long enough to take his tip from my own carelessly naked hand. A small fleet of such quicksilver heroes move from street to street every day; on our walk we see them darting from idling vans to front porches, delivering the goods. Once a week the heroic trash service takes away the remains of what they delivered: the cardboard and plastic, the grapefruit rinds, the chicken bones and wine bottles. Last week the local bookstore left a little sack of books on my porch: there’s no more idle browsing their aisles, but if I can target what I want, they are retrofitted to satisfy. And the missing members of my longtime reading group, who no longer live in Cambridge, now join us on Zoom. On Easter morning it was front-page news that two couples, all four of them now recovered from illness, were actually able to have dinner together in person. This is the melody of our lives now.

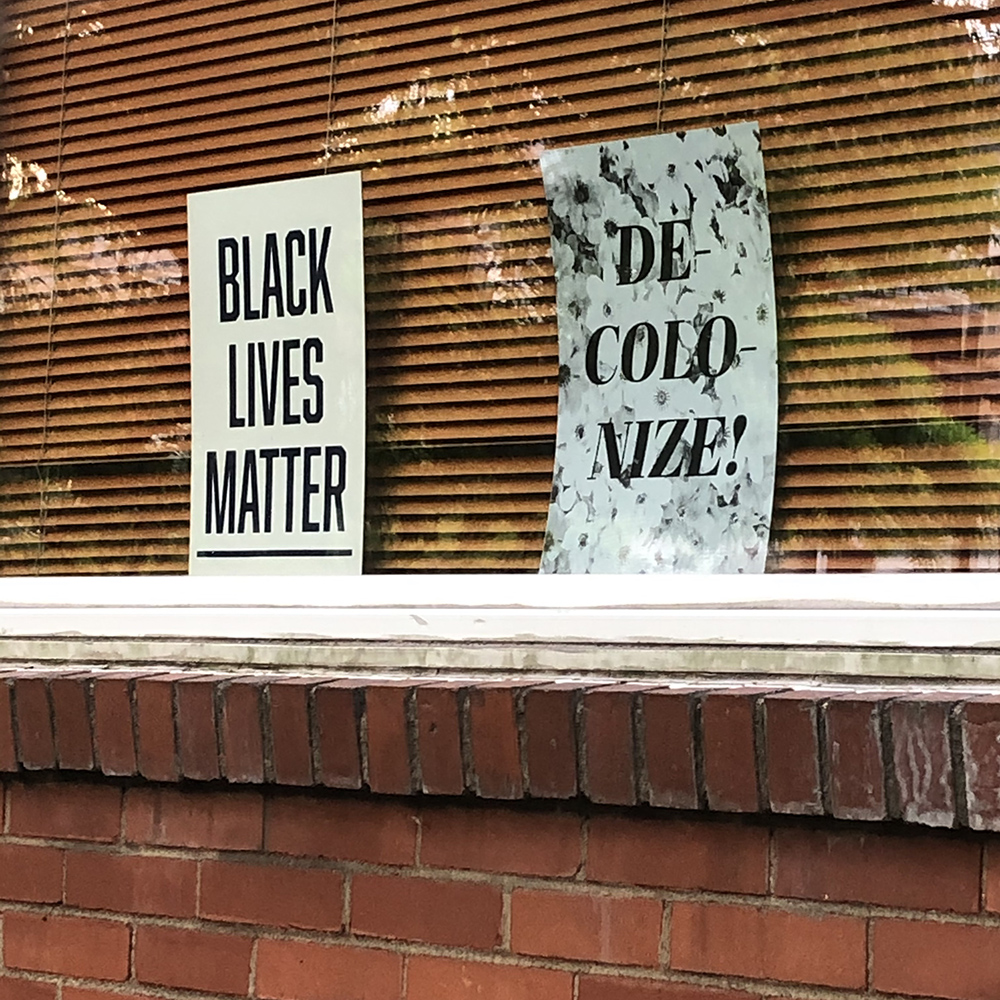

Meanwhile, the broken-hearted bass line beneath it keeps getting darker. The numbers are inconceivable, as are the suddenly suffocated lives and the scenes in hospitals and nursing homes. We see photographs of those whose masks are not a neighborly joke, but part of the flimsy armor available to protect their dedication and exhaustion. They are not invisibly smiling as they navigate the days and nights in emergency rooms or at dangerous bedsides. We don’t need Zoom to see images of cardboard coffins, of places where the idea of social isolation is a bitter joke. In this worldwide catastrophe we are ineluctably linked to one another and at the same time very distant. The breath of others is potentially pestilential; the sick and their caretakers live in a world where the lovely, indifferent spring is not the air they struggle to breathe. The plucky local delivery system doesn’t reflect the ruptures in Ohio, for example, where cows must be milked, but the milk is being piped into a lake because the markets that once needed it have collapsed. So we watch anxiously to see if the beautiful makeshift contraption of our democracy, and our uneven economic shelter, will withstand this viral mumbling, its ostinato rumbling that we are sinners in the hands of an angry God.

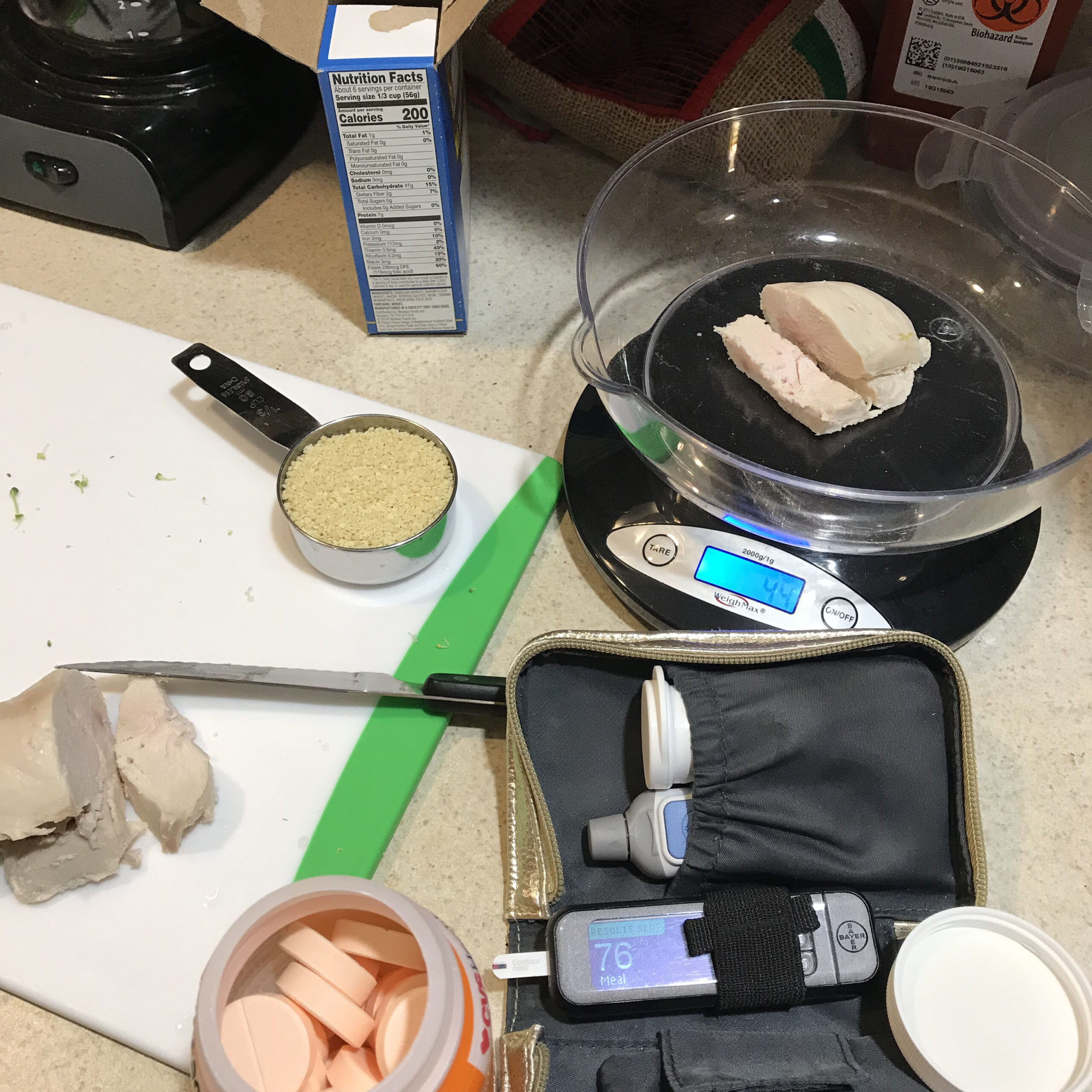

Even so, the city of Cambridge has reengineered the stop lights so we don’t have to touch the button for the walk sign. On the public basketball courts the hoops are draped in orange netting to discourage the feckless social contact of pick-up sports. At home we pull the old leaves off the flower beds, mulch around the shoots of green now reappearing, incredibly, miraculously, from the apparently undead earth. We stand in line six feet apart to enter the nursery and come home with half a dozen small pots of herbs: rosemary and parsley and Italian oregano … surely that kind’s the best.

Published on April 23, 2020