Return All You Took In: Poems by Arseny Tarkovsky

by Arseny Tarkovsky

translated by Alex Cigale

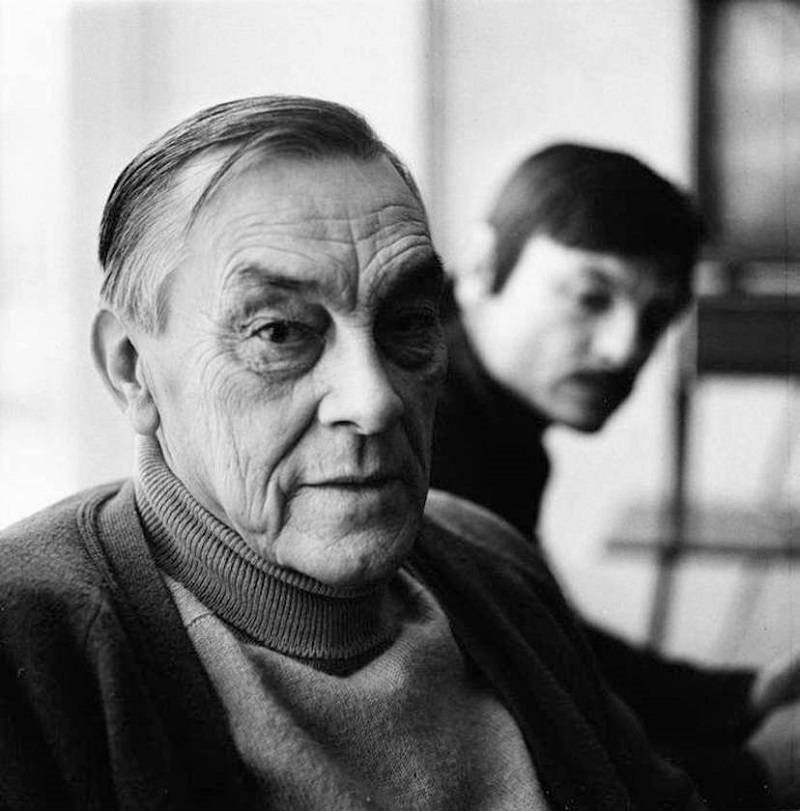

Arseny Tarkovsky (1907–1989), the filmmaker’s father, was perhaps the most technically and lyrically accomplished poet of Russia’s “War Generation.” He worked as a translator of poetry and as a war correspondent. Wounded in action in WWII, he suffered six progressive amputations of his leg. This experience was undoubtedly formative in shaping his poetic lexicon and personal cosmology. Injecting a mystical dimension and ironic sensibility into the narrative earnestness of Socialist Realism, Tarkovsky may be viewed as a transitional figure bridging the modernism of the Acmeist movement (part of the Silver Age of Russian poetry) and the postmodernism of later generations. He did not publish his first book of original poetry until 1962, during Krushchev’s Thaw, at age fifty-five. His work gained recognition only later, partly through its defining presence in the great films of his son, Andrei.

I Burned at the Feast: Selected Poems of Arseny Tarkovsky is now available in the English translation of Philip Metres and Dmitri Psurtsev.

Housewarming (translated with Dana Golin)

Moved to fulfill their faith’s diluvian decree,

Material bliss under fortune’s auspicious wing,

With all their things, amidst a day of moving,

Leaving their cave for the comforts of a new home.

How curious: only recently, the brush, measuring tape,

And cutting diamond ruled the roost, so that the Lord

Of Emptiness, enthroned along the nymph Neatness,

That nethermost of divinities, hid from us there.

Then, four heroes, none members of the teamsters union –

Atlas, Sisyphus, Heracles, and Odysseus – carried in,

As though bragging of avarice, flaunting their greed,

The packing containers, all splitting at the seams.

Like pagan priests treading an ecstatic jig,

With a pious plea of “Put some muscle into it!”

They dragged in the Popōcatepētl of the sofa,

Crimson like Eden on the first day of creation.

Having demonstrated their promethean prowess

Without as much as the use of their iron arms,

They hopped up on the five-bellied sideboard

And raised Aphrodite’s likeness on a metal stud.

Like a delicate slab of pinkish pork fat

She floated upon an ocean of blankets

Where the chandelier luminesced like a pheasant

And beyond the curtain dawn’s first light faded.

The four husband-men, having sung their reprise

Of Anadyomene’s embarrassingly lusty praises,

Departed.

The lady of the house, devoutly kneeling,

Took up the work of untying knots, unpacking suitcases.

The lord of the manor arranged the porcelain. A lesser man

Would not have succeeded in finding a common theme

In these:

the cups,

the dogs,

the pigs,

Napoleon,

and the lost

city of Kitej.

He looked for and uncovered the collected works

Of Molokhovetz—

and carried them to his office.

And every volume that this genius did create

He placed under a vacuum hose, just like Boreas.

Then, departing for a bit the confines of our time

And his new home with all its earthly possessions,

He jumped into a cab and raced back to the cave

Where in his childhood he’d crawled before the hearth.

There stood the Stump, great oak, six arms in diameter,

The Guardian of our birth and Giver of strength.

Oh, how once upon a time he loved that trunk!

How he had guarded it! How worshiped, idolized!

That Stump is now in the middle of the living room,

In the heart of marvel of the altar niche of all things,

And he proudly struts before the Greek goddess

His preeminence as the most ancient of beings.

And when the guests have gathered to celebrate

The housewarming and raised the roof on the house,

The proud owner, as in the olden days

his progenitor,

Chopped

the mammoth bones

to pieces

with an ax.

Dreams

The night alighting on the windowsill,

A pair of magic glasses on her face,

Like a pagan priestess reads aloud sing-song

From the thick Babylonian dream book.

All her ladder stairs lead upwards,

No handrails to guard the precipice,

Where shadows judge, as if on stage,

Your strange and alien-tongued reason.

Meaningless, countless, and without measure.

And who the referees? And what’s your sin?

We all emerged out of the common cave

And are guided by the same carved cuneiform.

From the Great Flood through Euclid’s forms

We are all doomed to see reality through.

Return all you took in, divulge all you had seen;

Your sons are calling you to join them.

On someone else’s threshold you will find,

In some great future, solace to ease the mind,

While the bulls, like gods, jostle in their ranks

And, clustered in the road, rubbing their flanks

Ruminate leisurely upon the cud of time.

The Azov Steppe

I jumped off between the stations. The cast iron rested

Immersed in giant spheres of oil-bespattered steam. He was

An Assyrian king all done up in clumps of clustered curls

And the steppe, opening wide, with its winds’ lacuna

Swallowed me up soul and all. No longer behind my back

The mud adobe hovels: ringed by the moonlit ziggurats that

Rippling inscribed themselves into the corners of the earth,

The night, unrolling its solid, densely woven cloth canvas,

Interpenetrated the nooks in the matrices of all dimensions.

My youth drained from me and the weight of my duffel bag

Made my shoulders hunch over. I loosened its belts

And sprinkled the bread with salt and fed the steppe,

And with the seventh share sated my patient flesh.

And I slept while pooling at my headstand cooled

The ashes of tsars and slaves and at my feet stood

A chalice filled with the Azov’s cup of leaden tears.

And I dreamed all that would happen to me in the future.

I came to in the morning and called the earth the Earth,

And stuck out my not-yet-hardened chest to the heat.

Published on February 17, 2017