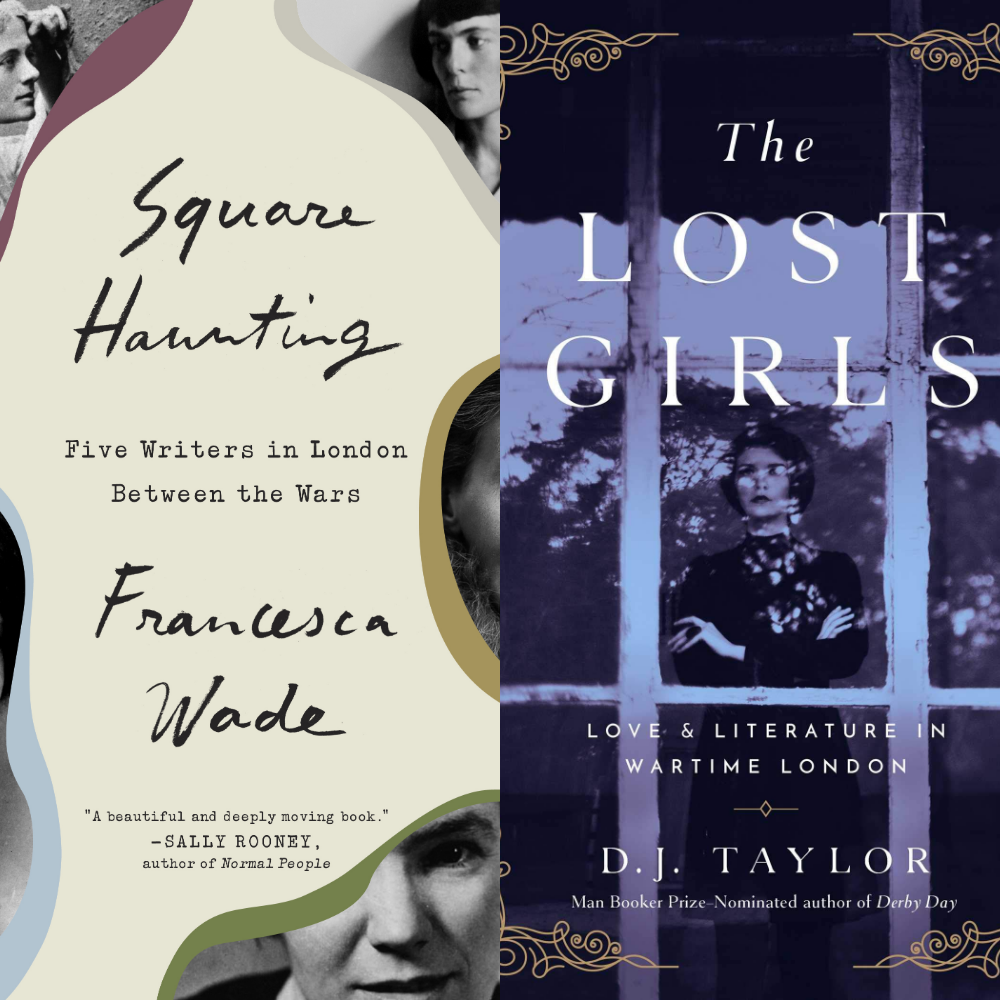

Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars by Francesca Wade (Tim Duggan Books, 2020)

The Lost Girls: Love and Literature in Wartime London by D. J. Taylor (Pegasus Books, 2020)

Contributor Bio

Laura Albritton

More Online by Laura Albritton

Rooms of Their Own

by Laura Albritton

During dull, uneventful afternoons of the COVID-19 pandemic I read two collective biographies, Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars by Francesca Wade and The Lost Girls: Love and Literature in Wartime London by D. J. Taylor. As I read them I was reminded that it is hard, indeed nearly impossible, not to read about the past through the lens of the present. We can’t help but draw connections, linking our current age and circumstances to those that have come before.

Square Haunting and The Lost Girls are both set in England, both overlapping with wartime, and initially I drew a connection to our own pandemic era, the so-called “war” against COVID-19. Yet the more I read Taylor’s and Wade’s descriptions of terrifying aerial bombardment over London, the less I thought of this global plague as a war. As I went on, I realized that it wasn’t war that was the connection, it was something closer, more personal: even more than war and wartime, Square Haunting and The Lost Girls address the lives of women.

In some ways, the two books could hardly be more different. They look at women’s lives from two different stances, with two different views of what biography can achieve. British writer and literary magazine editor Francesca Wade lays out her premise from the start: her aim in Square Haunting is to examine the lives of five women—poet Hilda “H. D.” Doolittle, mystery writer Dorothy L. Sayers, pioneering scholar Jane Ellen Harrison, economic historian Eileen Power, and novelist Virginia Woolf—during the periods in which they resided in one place, Mecklenburgh Square in London “on Bloomsbury’s easternmost edge.”

The square serves as a kind of glue, binding the five women together. Wisely, Wade does not push her premise too far, acknowledging that while the women’s lives occasionally intersected and their writings influenced one other, they lived in Mecklenburgh Square at different times. Still, she suggests, “their time in the square was formative,” and perhaps more importantly, their lives there “demonstrate the challenges, personal and professional, that met—and continue to meet—women who want to make their voices heard.” With these words Wade invites her readers to consider the fate of contemporary women alongside the circumstances of her five subjects. For some of us, this invitation may be irresistible; we feel invested in Wade’s project from the start. I know I did, especially during the quarantine, when so many women were, for one domestic reason or another, unable to write.

Wade wanted to know what sort of lives these women had lived “in these tall, dignified houses, where they had written such powerful works of history, memoir, fiction, and poetry.” Was it by chance that they had all shared this address, or “was there something about Mecklenburgh Square that had exerted on each of them an irresistible pull?” This focus on living arrangements made me think of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own—no coincidence, really; this is exactly where Wade wants us to go. What they were seeking, she concludes, was “everything Woolf had urged women writers to pursue: a room of their own, both literal and symbolic; a domestic arrangement which would help them to live, work, love and write as they desired.”

One of the pleasures of reading Square Haunting is Wade’s gift for description, her sitting rooms with “statues of the Buddha, a brown teapot, its leaves dumped on pieces of newspaper … overflowing ashtrays,” or the Zeppelin attacks during World War I: “the hoarse wails of bombs and shells piercing the atmosphere, antiaircraft guns bursting like firecrackers.” I often felt I was there, in those places, only to look up and discover: still quarantined. Yet always the absorbing historical narrative exists within a book of ideas. The biographer places her subjects in intellectual dialogue with one another; we see, for example, how H. D.’s poetry exploring a “powerful, independent” Eurydice and other mythological figures connects to the work of Virginia Woolf, Jane Ellen Harrison, and Eileen Power.

In her chapters on the mystery writer Dorothy L. Sayers, Wade argues that in her fiction Sayers depicted the kind of life that many women artists long for, even today. In Gaudy Night, the most successful of her Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries, she tells the story of Harriet Vane, a fictional writer who lives on Mecklenburgh Square. With Wimsey, Vane manages to achieve “a partnership that will not degrade [her] or curtail her freedom, but rather provide the conditions under which her writing will flourish.” Sayers’s hero, Wade writes, instinctively realizes the importance to her heroine “of a room of one’s own.”

Sayers persisted in her profession despite “scorn from male contemporaries who dismissed her work,” as did the classical scholar Jane Ellen Harrison. Another resident of Mecklenburgh Square, Harrison fought for decades to win academic positions for which she was disqualified because of her sex. She wrote the groundbreaking Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion and conducted archeological investigations that would “shake the foundations of classical scholarship.” Learning that Harrison’s “efforts to reread history through the lens of gender” influenced both Virginia Woolf and her sister Vanessa, I was again struck by how revolutionary these women were.

During the last year of her life, Virginia Woolf lived on the square until it was damaged in the Blitz. Wade masterfully recreates Woolf’s final year, reminding us of the author’s observation that, “until very recently, women in literature were the creation of men.” By detailing their professional and personal lives, their publications, and context in which they lived, Wade demonstrates that all five of these women were engaged in, to use Woolf’s words again, “another way of writing about women.” One can’t help but be convinced that, “In a sense, all these chapters tell the same story, that of A Room of One’s Own, that which Woolf portrayed in her memoirs: of a struggle to be taken seriously, a move to a new place, a quest to find a way of life outside the traditional script.”

•

Women’s struggle to be taken seriously is also an issue in The Lost Girls: Love and Literature in Wartime London by the Whitbread-prize winning biographer D. J. Taylor. Taylor considers a group of women—Lys Lubbock, Janetta Woolley Parladé, Sonia Brownell, Barbara Skelton, Joyce Frances “Glur” Warwick-Evans, Angela Culme-Seymour, Anna Kavan, Diana Witherby, and Joan Leigh Fermor—“who fizzed in [Cyril Connolly’s] slipstream … whom at various times he employed, fell in love with and very often schemed to marry, and over whom he cast a spell.” Cyril Connolly was a larger-than-life English writer and the editor of the literary magazine Horizon, much celebrated in his lifetime. This is the story of “the girls who during the 1940s and in varying degrees after it were the handmaidens at [Connolly’s] court.”

Because The Lost Girls arrived in the mail first, I read it before Square Haunting. I was eager to learn about these women and the very masculine literary world they entered in the 1930s and ’40s. The first chapter, “The Wanton Chase,” begins in 1942 with a party at Cyril Connolly’s and focuses on the historian and essayist Peter Quennell and his libidinous desire for one “girl,” Barbara Skelton, while being married to another. Quennell recalled, “What distinguished [the lost girls]—and used to touch my heart—was their air of waywardness and loneliness.” More of this sort of thing follows, with Taylor paying considerable attention here, and throughout the book, to the women’s “startling—at times almost outrageous—beauty.” Taylor writes of their sexual allure, their unstable home lives, their limited educations, giving us juicy paragraphs on Cyril Connolly and glancing mentions of the Brideshead Generation and Bright Young Things.

Male desire and female objects of desire are a consistent theme. I have to confess I groaned when I saw the chapter entitled “The Little Girl Who Makes Everyone’s Heart Beat Faster,” which opens with poet Stephen Spender’s description of Janetta Woolley. “No literary or artistic bohemian of either sex who chanced upon [Woolley] in her mid-century heyday seems either to have forgotten the experience or to have been anything other than transfixed by her company,” Taylor writes. Someone else is quoted observing, “She’s rather a cock-teaser.”

Here I began to feel my dispassionate stance as a reviewer slipping. I had no issue with Taylor describing the lusty male writers’ gaze, but I wanted to know more about the women. I was hungry for a book that addressed women not as objects but as subjects, but having reviewed books for almost two decades, I carried on dutifully. To give but one example of what I found: the narration of the teenaged Janetta Woolley’s abortion comprises four perfunctory sentences; Barbara Skelton’s abortion, a single sentence. No pause to consider that the operation was at the time illegal, the potentially enormous scandal of pregnancy outside marriage, or the psychological impact of coping with it. I hadn’t yet read Wade’s biography (in which she does consider all these implications), but I knew that another biographer, even another male biographer, might have considered these issues serious enough to warrant attention.

Although the “lost girls” wrote diaries, letters, and books (Skelton published five, Kavan sixteen), quotations from them are sporadic. Meanwhile, the book is liberally sprinkled with quotations from Connolly, Evelyn Waugh, and other famous male writers and intellectuals. At the start of the volume, Taylor writes that “although long stretches of it are concerned with his habits, achievements, and influence, this is not a book about Cyril Connolly.” The hitch is that there would be no book without Connolly, and the “girls” remain mostly “handmaidens.”

Fifty years ago, in 1970, Simone de Beauvoir published The Coming of Age, and in it, she writes, “As men see it, a woman’s purpose in life is to be an erotic object.” I was born in 1970, and from my experience growing up in America, I’ve found this to be less and less the case. Certainly, women still struggle to make their voices heard and to be taken seriously, but the world has changed and continues to change. It is, as they say, a work in progress, and an imperfect one at that. Those of us lucky enough to be working safely from home during the pandemic are battling the inconveniences of family racket, endless laundry, unrelieved domesticity, caretaking, and so on, but we are not battling the forces that Jane Ellen Harrison, Dorothy Sayers, or, indeed, Barbara Skelton battled. We are freer than they were. We are even free enough to know which type of history we prefer.

Published on November 12, 2020