Santa Barbara

by Gillian Osborne

Last night, I came home early from a two-night, two-family campout. We’d driven thirty minutes up the coast in search of other realms of experience: a crowded, mostly shadeless campground, tucked under a railway trestle, mountains on one side, a narrow beach on the other, highway song and the soundtracks of neighbors (country, trance). On day one, we threw ourselves into the ocean, talked loudly, wept (some of us), and didn’t sleep much at all.

We pulled our masks on to use the public restrooms, avoided other groups, and were grateful for the fog in the morning and the geological uplift that made the cliffs a sideways wonder. In the evening there were bats and in the morning California quail, ushering each other around in flocks. But there was also this: a low hum of what-will-we-do-now, now that the schools are not going to open in just a few weeks.

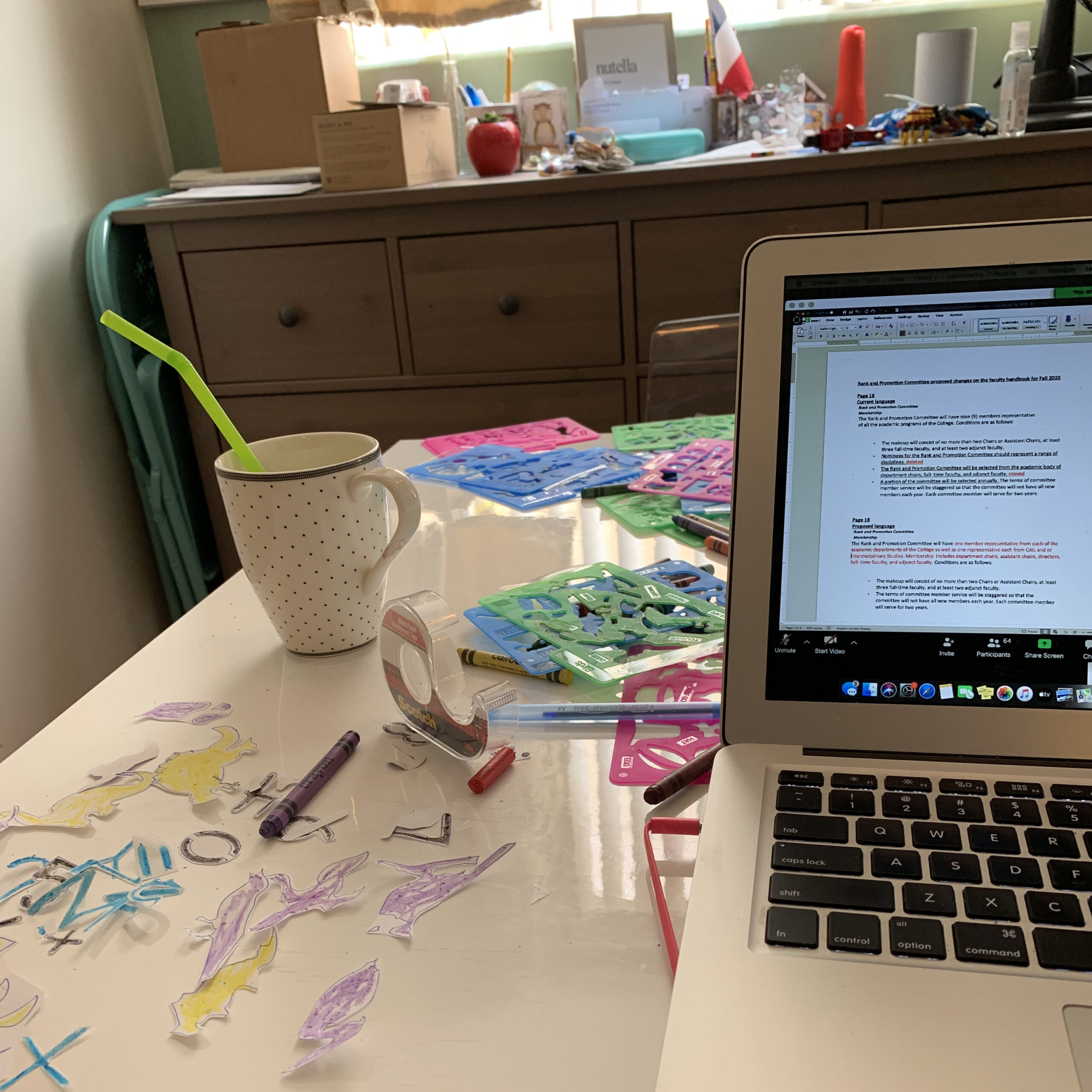

There was a wild determination on the part of all these families, including ours, to act as if this were a real summer: kids body-slamming waves, roasting meat sticks and marshmallows over the fire. But before we know it the five-year-olds will all be sitting down at iPads, logging into kindergarten. While we do what, exactly, in the hallway?

By night two I’d come to feel that a real vacation would be sitting alone in a house with a book. With everyone at home and rotating pod-care, solitude has become as scarce this deep into the pandemic as toilet paper was early on. I hitched a ride down the coast with the other pod family, their twins telling knock-knock jokes and interrupting each song to ask for another the whole way home.

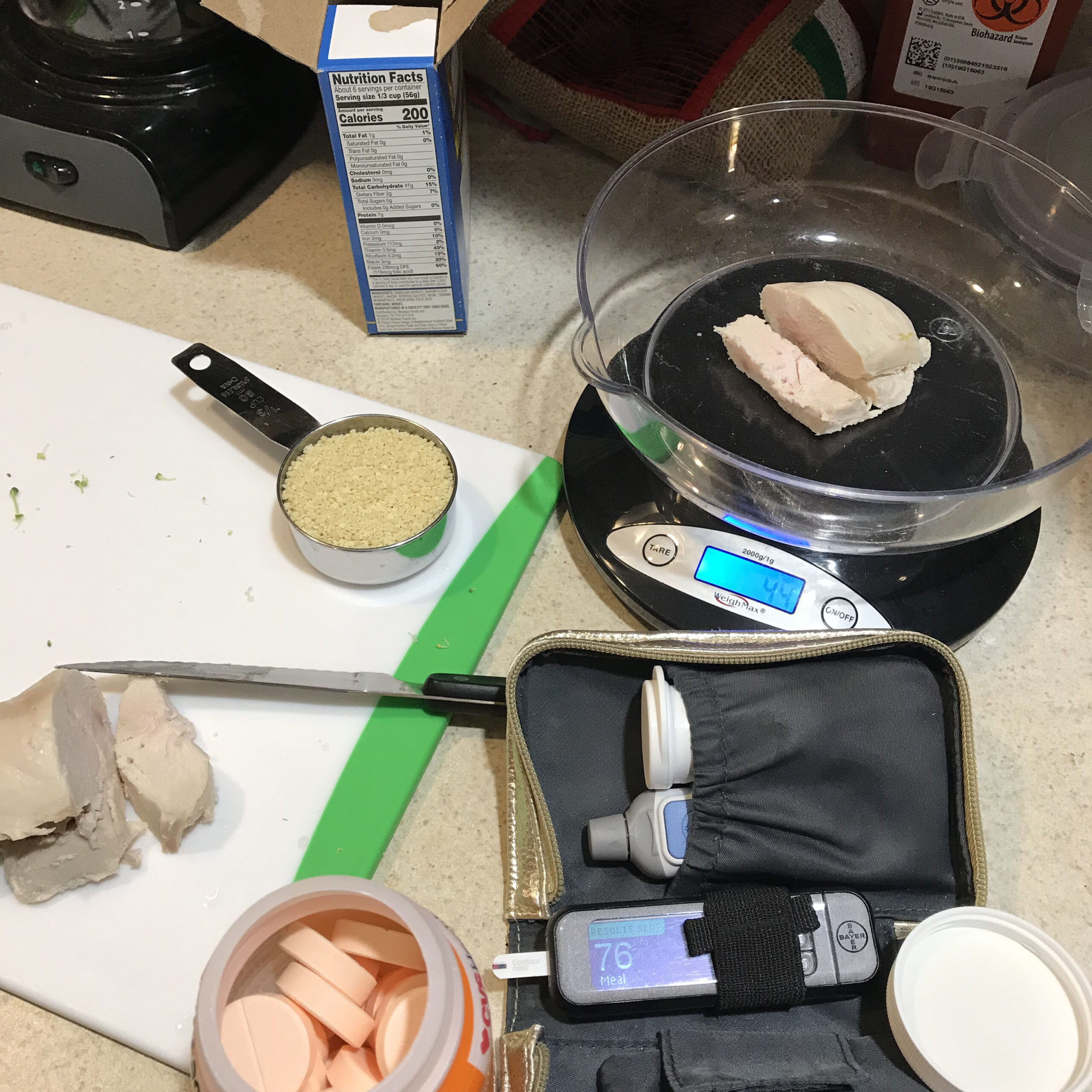

By myself, I fed the fish, took a shower, read Marjorie Perloff, and fell asleep. In the morning I sat down to do the work that never would have happened at the edge of that shared semi-wild. I read Elizabeth Peabody’s letters to William Wordsworth and her preface to a Record of a School. Like Wordsworth, Transcendentalists like Peabody believed the natural world had an educating drive and that children become “intoxicated with play.”

When we first moved to California two years ago, we enrolled our son in a play-based preschool and a wilderness education program one day a week. While we worked, he spent his weekdays roving with packs of three- to five-year-olds. There wasn’t much talk of letters, numbers, shapes, but he did learn the names of wildflowers and the calls of birds. When these programs stopped in March, that messy, social, experiential learning came to an end. For the first time since maternity leave I was parenting full time. There were days when I tried to be a preschool teacher, a playmate, a wilderness steward.

I’m grateful to have had this time. But I also wish I were about to turn my son’s education back over to someone who has thought a lot about how to teach a child to read or count, what it means to be a writer before you know how to write. I want him to learn the pleasure of being alone with a book, and what it means to belong to a social context larger than a family, a pod, or a campground of strangers in masks.

Published on September 1, 2020