Situating Max Jacob in English

by Kevin Gallagher

A review of four collections:

The Central Laboratory by Max Jacob translated by Alexander Dickow (Wakefield, 2022).

The Dice Cup by Max Jacob translated by Ian Seed (Wakefield, 2022).

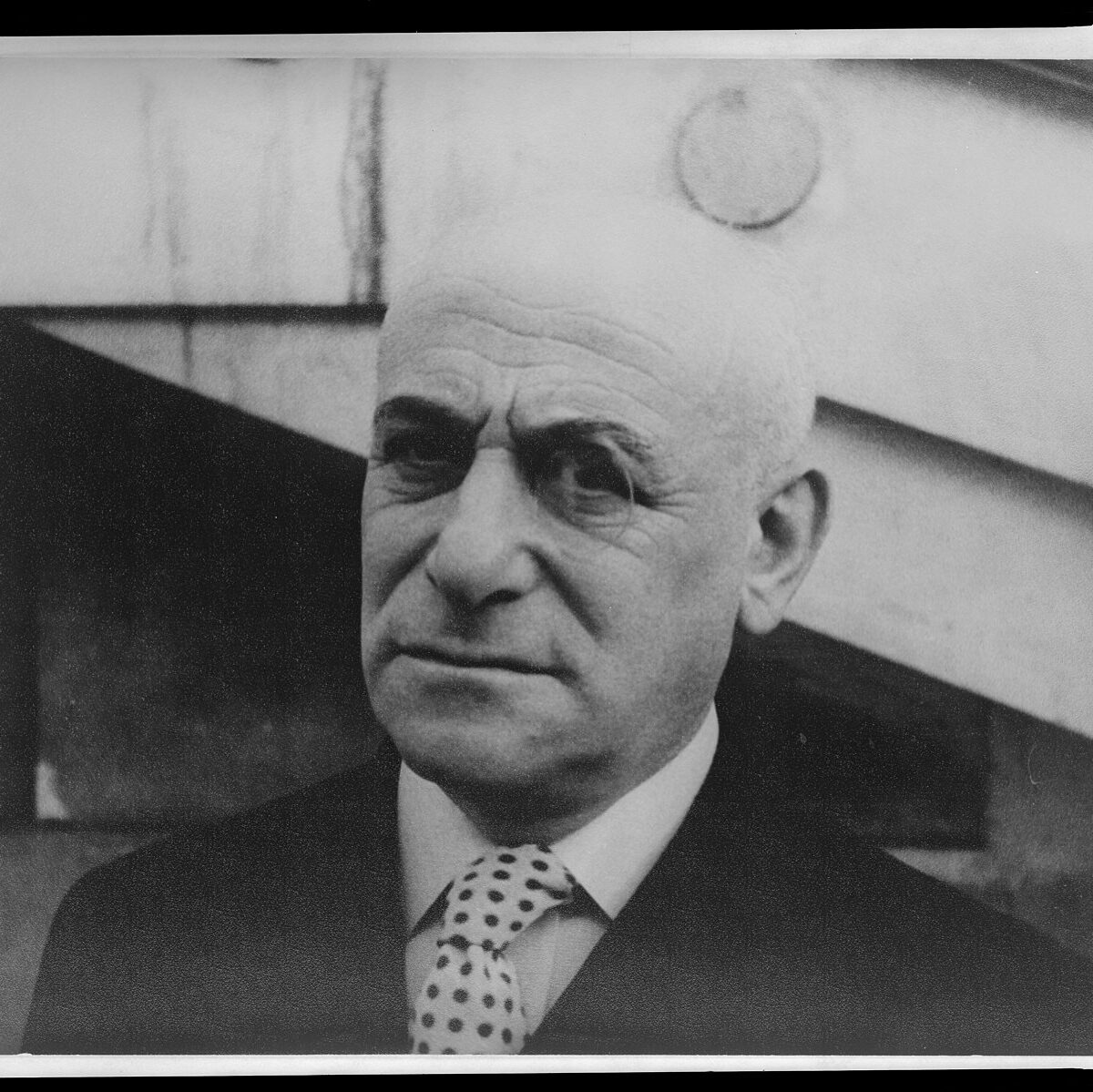

Max Jacob: A Life in Art and Letters by Rosanna Warren (Norton, 2020).

The Thief of Talant by Pierre Reverdy translated by Ian Seed (Wakefield, 2010).

My first encounter with Max Jacob was at the end of the third movement in Kenneth Rexroth’s Thou Shalt Not Kill: A Memorial for Dylan Thomas. The poem is a shrilling scowl at modern society’s ability to destroy the most creative minds of the times, starting with Thomas and continuing:

‘Rene Crevel!

Jacques Rigaud!

Antonin Artaud!

Mayakovsky!

Essenin!

Robert Desnos!

Saint Pol Roux!

Max Jacob!

All over the world

The same disembodied hand

Strikes us down.’

Upon hearing the poem performed with the Cellar Jazz Quartet, where Rexroth reads the names along with a loud marching snare, each followed by a cymbal clash and trumpet pip, I immediately went hunting for the work of the poets he named (event though I didn’t speak French or Russian).

In his The Poet as Translator, Rexroth said that a great translation in English is not ‘engaged with matching the words of a text with the words of his own language.’ That might fly for prose, but not poetry. In poetry, I believe a great translation must be a great poem in English while still maintaining the spirit, sound, and meaning of the original. By that measure, Clayton Eshleman and Jack Hirschman put Artaud and Mayakovsky straight into my young marrow, though unfortunately the books of translations of Jacob I found had no such impact.

One of the books that I have cherished since those early French poetry pursuits was Rexroth’s translation, Pierre Reverdy: Selected Poems. I spotted it on the shelf at the Brattle Bookshop in Boston in the late 1980s—the New Directions 1969 first edition with a perfect dust jacket of Juan Gris prints. In the upper right-hand corner ‘7-’ is written in light pencil. I have read from the book just about every year since. From “The Same Number”:

The hardly open eyes

…….The hand on the other shore

The sky

…..And everything that happens there

The leaning door

Later on a trip to Paris in 2017, I bought a copy of Ron Padgett’s translations of Reverdy’s Prose Poems and fell hard all over again. Padgett’s translations of these prose poems are a new syntax of the word and the mind that maintain a such a sense of clarity they can be explained to your friends over a drink. In a short essay at the end of the book, Padgett notes that the original 1915 self-published version of Reverdy’s Prose Poems with Juan Gris and Henri Laurens covers was dedicated to Max Jacob as well as Picasso, Gris, Matisse, and Braque (Though in subsequent editions he removed their names). From “The Poets”:

His head took shelter beneath the lampshade. It is

green and his eyes are red. There is a musician who does not

move. He sleeps. His severed hands play the violin to make

him forget his poverty.

When I returned from Paris, I found another translation I’d never heard of, Reverdy’s The Thief of Talent, translated by the English poet Ian Seed and published by Wakefield Press in Cambridge, MA. When Reverdy had turned up francless in Paris in 1910 at the age of 21 after his father’s vineyard went bankrupt, Picasso, Apollinaire, and Jacob were already at the center of the new art and poetry and Jacob took him on as a mentee.

The Thief of Talent is a long reflective narrative dreamscape poem about life in Paris. Seed says the idea for ‘The Thief’ came about when Reverdy was looking in Jacob’s trunk full of manuscripts. When Jacob slammed the lid shut, Reverdy felt kicked out of the club, and moved to make his own mark. Central to the book is a magician and a thief who revered his master and:

….Diving into the half-open trunk to

…….take everything that was left.

And when he looked back up his head was swollen

He carried away everything there was

……………..to take

In 2020, Rosanna Warren’s wonderful seven-hundred-page Max Jacob: A Life in Art and Letters was published, and it is there I learn that the third poem in Reverdy’s Prose Poems, “Envy,” is dedicated to Jacob:

Lightly he touches whatever

he picks up, everything goes his way and I feel my head

crushing the fragile stems.

Warren goes on to tell us that the poems Reverdy read in his snooping were Jacob’s prose poems that would eventually be published as The Dice Cup. Jacob thought he had been pioneering an evolution of the prose poem beyond Mallarme (Jacob’s title is talking to Mallarme’s A Throw of the Dice) or Rimbaud, but after showing them to Reverdy he claims that Reverdy then rushed to publish his own prose poems in 1915. Jacob accused Reverdy’s prose poems as mere imitations of his own in a 1916 essay in 291, Alfred Stieglitz’s magazine at the time. Despite this rift however, Reverdy and Jacob were fairly close for decades to come. In fact, Reverdy later published some of Jacob’s prose poems in Reverdy’s now famous journal, Nord-Sud.

Paper and printing shortages from the war, as well as Picasso’s procrastination with the accompanying illustrations, delayed publication of Jacob’s masterwork of the prose poem–The Dice Cup. It took more than 60 years more for some of these poems to be published in English translations of any merit, most notable being the anthology published by Sun Press in 1979 and featuring translations by John Ashbery, Padgett, and others. And it isn’t until 2022 until we get the full volume in one beautiful bilingual volume, translated by (the previously mentioned) Ian Seed and published by Wakefield Press in Cambridge, MA.

In Warren’s biography she shares that she learned that the essay in 291 evolved to become Jacob’s famous preface to The Dice Cup where he declares that prose poems are ‘situated’ at a distance from real life but spun through the particular style of the author. Warren quotes a Jacob passage in Nord-Sud where he says ‘A work of art is significant in itself and not through comparison with reality.” And, from the Seed translation of the intro itself “Style is the will to exteriorize oneself by one’s chosen means…..The author, having situated his work, can make use of all kinds of charm: language, rhythm, musicality, and wit. Once a singer has his voice in tune, he can enjoy himself in vocal embellishments.”

Seed’s translations of Jacob are as masterful in English as they are in French. Now we can see the great (prose) poetry that set off a revolution there and here. In The Dice Cup, Jacob tells stories through a mosaic of snapshots or film clips that run backwards and forward at the same time with allusions of the classics, of comics, of irony simultaneously in space. You will need two copies of this one—one for the shelf and one to always have in the backpack.

Here is one of Jacob’s prose poems for Rimbaud, titled ‘Not my Kind of Poem,’

Apollo was a doctor, and I’m a pianist at heart. If not in

reality. With the flat notes and sets of bars, one would have to

unload sketched steamers and collect the tiny flags in order to

compost canticles.

Another poem in the book has the same title but is dedicated to Baudelaire and ends:

Beside them was a young woman, crowned with artificial

ivy who said, “I’m bored. I’m too beautiful.”

And God from behind the holly bush:

“I know the universe, and I’m bored.”

There is a long untitled sequence of short stills. In the Seed translation one reads:

When one paints a picture, it changes with each touch.

It turns like a cylinder and is almost endless.

When it stops turning, the picture is done

Jacob met Picasso in Paris in 1901 and together with Apollinaire, they were three poor and little-known artists who would go on to become world famous. Warren identifies the same poem and translates slightly differently, but situates the poem in the poet’s life to see that part of the sequence is a reflection on Picasso:

‘When you paint a painting, at each touch,

it entirely changes; it turns like a cylinder, and it seems interminable.

When it stops turning, it’s finished.’

In 1921 Jacob published his greatest book of verse, The Central Laboratory, and 100 years later in 2022, Wakefield Press published a new translation of the work by Alexander Dickow. Dickow’s task is formidable as the poems in The Central Laboratory are filled with music, and Jacobs builds mosaics of strict form, mime, doggerel, and absurdity in each poem. Unlike The Dice Cup which always rolls with a distant sense of reality, Warren states that ‘sound often leads sense’ in many of the poems in The Central Laboratory. Indeed, Warren acknowledges that the volume is among Jacob’s most accomplished while also stating Jacob ‘may have to wait for the twenty-first century to find a hearing sympathetic to this wild narrative.’

Dickow describes how he struggles to mimic all the details of Jacob’s verse techniques in English, saying the best technique was to work at it line-by-line. He refers to French critics who term Jacob’s verse poems as ‘of the cock to the donkey’ which is seen as an absurdist nonsense verse that scats separate cubes of commentary across space and sound. Read aloud, the poems sing and stop and paint and ring depending upon the line. In the last section is a stampede of a symphonic series of poems about a ‘Masked Ball:’

Posthumous ball in costume

Where the crowd is inflamed for not having lanced its imposthume

And is impertinent. If this mob sneers

At ideal artichokes. The chandeliers

That whisper icy poles to frescoes

…In the manner of Watteau, full of meadows

And airy boats that sail the woodland beauty

(Meadows always rhyme with Punch and Judy)

Warren also flags that in The Central Laboratory, the list of previous works by the author gives the publication date of The Dice Cup as 1915, the year Reverdy published Prose Poems. However fun and intriguing this drama is however, I believe it was simply a case of youthful ambition with Reverdy as an early second-generation Cubist merely looking to outdo his masters as Jacob and Reverdy were in touch for many years after their rift. Jacob ultimately became so well known that he retreated to a monastery in Saint Benoit, where he attended mass daily and wrote. In 1909, Jacob, who was of Jewish descent, converted to Catholicism and later left Paris for monastery life though he was later found by the Germans and died of pneumonia before he could be transferred to Auschwitz.

One hundred years later, after inspiring legions of French and American poetry, not the least of whom were John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara, these poets have been reborn in the English language. Thanks to Rosanna Warren, Ian Seed, Alexander Dickow, and Wakefield Press for bringing them to us.

Published on June 6, 2024