Strasbourg

by Ophelia John

I stand in front of store shelves containing tahini, peanut butter, almond butter, five brands of hazelnut-and-chocolate spread and I think, Am I crazy? Everything seems so normal.

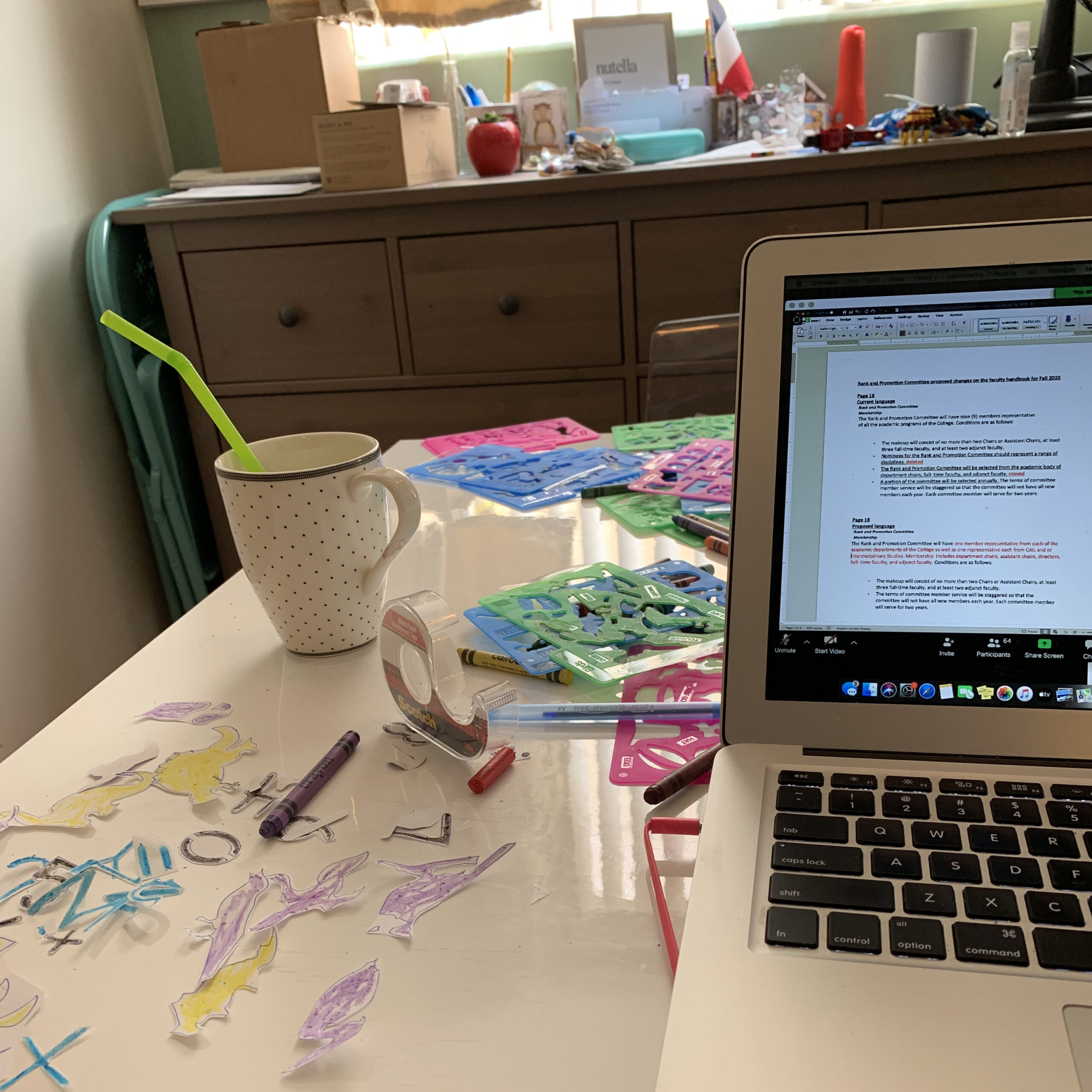

Late February, my friend Silvia is quarantined returning from Italy and I start tutoring her kids online. Then the border with Germany closes and with it our access to our doctor, my husband’s job, his parents and siblings.

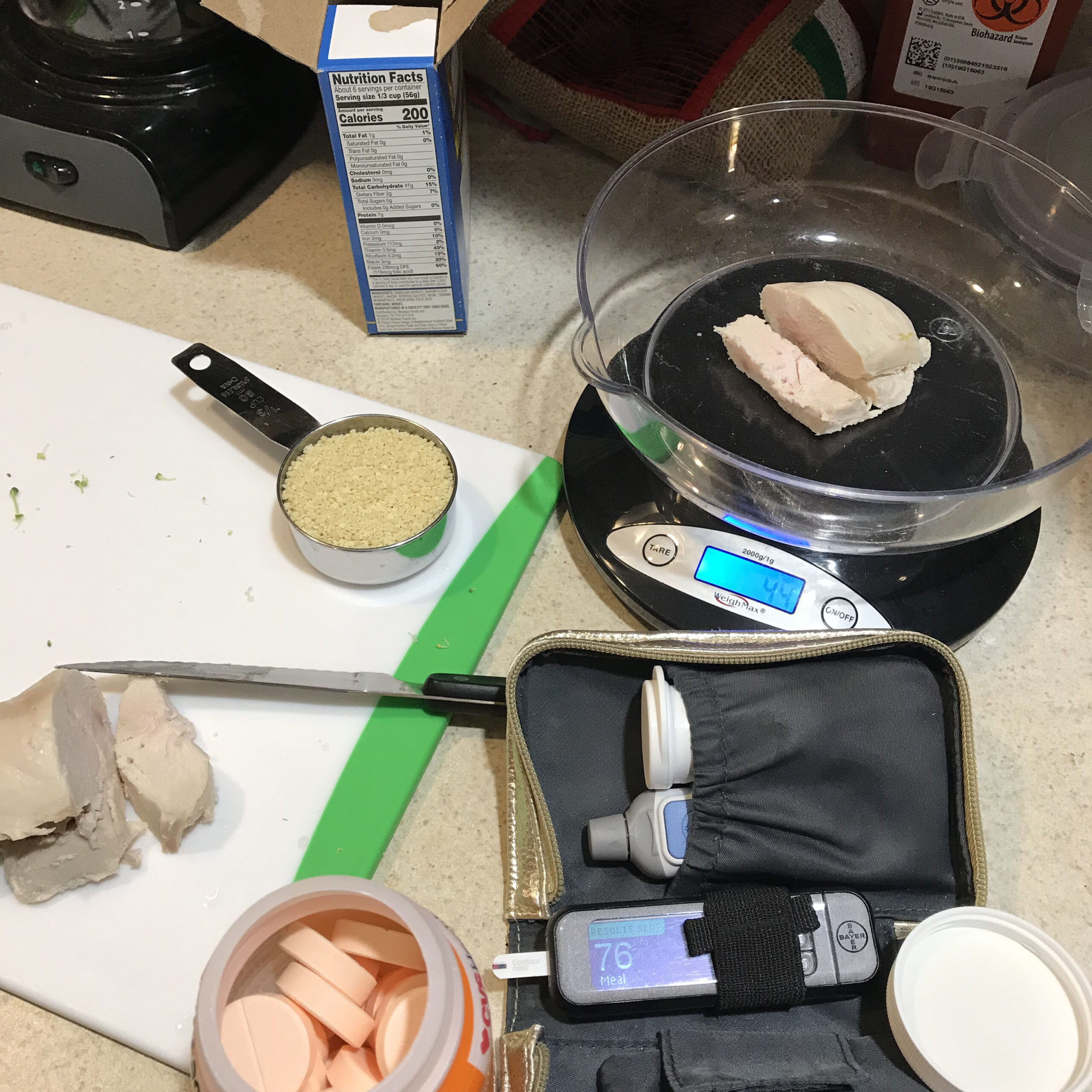

Our region has the most infections in France. I want to stay in and hide, but the probability of catching the virus is only going to increase from here on out. We have to buy more food.

In the shop, the lentils are already gone. I grab cheese, milk, eggs, flour, sugar. The woman behind me in line pushes closer and closer. Outside, I throw away the useless gloves that have already touched the refrigerator handles, the food, the bags—everything.

If you have neighbors who are healthcare workers, President Macron says, please offer to take care of their children. From noon tomorrow, the whole country is under confinement. We can go outside only for a short list of basic reasons and must carry a signed attestation de déplacement dérogatoire. Police will be checking.

At 8 p.m., an invisible neighbor blows a vuvuzela and people open their windows and clap in the darkness, lamps glowing behind them.

New rule: five people at a time in shops. People wait on the sidewalk. Inside the bio-market, a young woman in a tawny velour tracksuit coughs without covering her mouth. The cashier’s station is fronted by a wall of Saran Wrap, so that when I lean forward to gather my groceries I end up kissing the transparent film.

The authorities change the attestation: maximum one hour of outdoor exercise daily within one kilometer of your house.

There is no meat, fresh milk, cheese, yeast, or toilet paper in the neighborhood shops.

From our apartment, we hear sirens in the nearly empty streets. Silvia drives to the supermarket and buys milk and meat for us too. The police stop her and tell her to shop near home.

The clocks turn forward. Now, when the clapping starts, we can see our neighbors, but nobody makes eye contact. After one minute, balcony doors and windows shut and everyone disappears like the man and woman in a Wetterhäuschen.

I smell it before I see it: a lilac, tucked away in someone’s garden near the canal.

More than 900 deaths in Alsace, but infections are declining.

Armed with our attestations, we take a bottle of Sancerre and our own glasses to Silvia’s balcony, keeping more than a meter between us and them. When the police drive by, we all duck at once.

We meet an elderly neighbor on the stairs. If you need anything, I say, our last name is John. Like John Travolta, he laughs.

Macron—sober, apologetic, urgent—announces the continuation of the confinement.

At eight o’clock, the neighbors pop onto their balconies and stand in their windows and look around at each other—the middle-aged couple with white-striped curtains, parents with small children holding pots and pans, three shirtless boys in their attic dormers. High above the new green of the chestnut trees, the birds go free.

Across the street, a woman waves to us. Bonjour, she says, bonjour.

Published on April 23, 2020