Three Demons: Haiku by Sanki

translated and introduced by Ryan C. K. Choi

Introduction

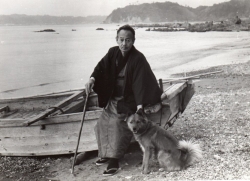

In 1925, the year of his graduation from dental school and his marriage to Shigeko Uehara, Keichoku Saitō emigrated with his wife to British Singapore at the invitation of his brother, Takeo, twenty years his senior and the family head since their father’s death in 1906; rather than tending to his fledgling career, however, the profligate younger Saitō (born 1900) reveled in the city’s cosmopolitan culture, hosting extravagant soirées at the building his brother had purchased for him as a wedding gift, taking up golf and ballroom dance, making foreign friends and taking a string of lovers, all to his brother’s disapproval. Only three years later, sick with typhus and already bankrupt, Saitō was forced to return to Japan amidst Singapore’s growing recession and a rise in anti-Japanese sentiment precipitated by the hostilities of the Imperial Japanese Army in China. Following another failed attempt at a clinic back home, Saitō obtained a position as head of the dentistry department at a hospital in Kanda, Tokyo, where he befriended a colleague in the department of urology, a specialist in venereal disease and a haiku enthusiast who invited him to contribute verse for a collection he was assembling of haiku written by his patients. Saitō, initially averse to what he saw as a stale form, began to write only reluctantly, after considerable prodding from his colleague and his colleague’s patients, who, for them to have been so persistent, must have sensed a unique sensibility. With characteristic impulsiveness, while conferring with the editor of the publishing house that was printing the urologist’s collection, Saitō adopted the pen name “Sanki” (meaning “three demons”), and, contrary to tradition, did not name a master under whom he had apprenticed (for there was none and never would be). Soon after his first writings appeared, he accepted an offer to become a contributor to the Kyoto University-based magazine, Kyōdai Haiku, and from there his reputation as a nondogmatic, self-expressive iconoclast spread, and in the mid-1930s, upon recovering from tuberculosis, he quit dentistry to focus on writing, taking a desk job at the commercial firm of a friend from his much-missed Singapore days. As a testament to his maverick reputation, he was imprisoned in 1940 during the government’s World War II persecution of avant-garde artists, and was officially forbidden to write, being deemed especially pernicious for his perversion of traditional literary forms: in his body of work, which resists simple summary, the classical moraic rules and kireji (punctuative expressions) are often intact; the seasonal references (kigo) are neither religiously heeded nor scrupulously avoided; and he tended to write in thematic sequences instead of stand-alone units. Once he was freed from prison, Sanki, obedient to the will of the government, relinquished literature. He abandoned his wife and son in 1942 and moved to the port city of Kobe, living first in a crumbling hotel and later in a dilapidated occidental mansion in the hills, regularly receiving visits from friends, lovers, and admirers. When the war was finally over, he took up his pen again, as well as his dental pick, his sole means of sustenance, until he was promised a position in Tokyo as chief editor of Haiku, a magazine run by the owner of the renowned publishing house Kadokawa. Sanki gladly accepted, laid down his dental pick for the final time, and at the age of fifty-six moved back to Tokyo, where in 1962, just shy of his sixty-second birthday, he would die of stomach cancer.

“THREE DEMONS”: SANKI SERIES I EXTRACT

Cannon fire.

Land

and sea

life freeze,

stares

go grim.

Moor of ruin,

my sister’s grave—

I lift her into the light.

Pine cones

A town underground—

a

magician’s

wiggly fingers.

Sliver

Flag

of the German Academy—

snow

flecked, rippling

in

the breeze.

Machines

Trains and women

depart;

inauguration

of a

lunar eclipse.

Black mass

Fair weather

morning.

Boys

peer at

the distant

castle.

Left eye

Early noon—

under a cascade

of pine

cones, I purchase

a black

mourning band.

Rooftop

Bonfires we

stoke, pierce

the

morning

sun and

shadows

we stoke.

Rooftop—

a doctor flapping

his arms in

the biting

cold.

grim. Moor of ruin

Through

a parched

meadow, a father

mumbling drunk

zigzags

home.

Mourning

As the train

enters the

snowy pasture, the

riders stop

speaking.

In mud

Left

At midnight,

crickets,

twitching on the

cliff

in the cold.

Translator’s Note

While every translation makes different demands, it invariably feels like an upriver swim. One challenge with haiku is that the genre draws on an exhaustive collection of nuanced seasonal expressions and a specialized grammar that doesn’t appear in common prose or speech. In the early stages of a translation, I do more elementary learning than anything else just so I can read the work fluently, juggling multiple texts besides the original and my own—dictionaries and thesauri, encyclopedias, secondary sources, message boards, pictures, video and audio files, anything useful that I can locate electronically or in the library. Once I feel I’ve mastered the source text I set it aside—as a concert pianist does with a score after committing it to memory—and concentrate on the translation alone, revisiting the former only to prevent undue drift, some of which is inevitable, even desirable, if one wishes to kindle the original muse. In this, the translator retains considerable editorial clout, and in the course of translating a piece channels a range of editorial philosophies, depending on the text and the language-pair being bridged. Where to cut, what to add, what to keep—there are no definitive guides to this. What takes three words in Japanese sometimes takes fifteen in English, and vice versa. Moreover, with Japanese, the translator into English typically can’t rely on the source sentence as a direct syntactical map. This is not always the case with other language-pairs. Every pair has its own peculiarities and attendant difficulties.

Haiku in Japanese are written as a single vertical line composed of three phrases. The traditional metrical array is 5-7-5. The numbers refer to the beats (called on, pronounced “ohn”) per phrase. These rules of form, as well as those of content (seasonal referents, cutting words, dichotomies of “transience” and “permanence”), arose from within the properties of Japan, with—to name a few—its sharply contrasting seasons and local and imported spiritualities, and of the Japanese language itself, which, on a character-by-character basis, is morphemically far denser than English. When a writer of English haiku, in search of comparable restraints, translates the 5-7-5 rule syllabically, the result has a somewhat tenuous, arbitrary relationship with its new linguistic surroundings. In English, since the haiku is a comparatively recent import, one sees even starker dislocations of acceptable form (haiku ranging from one to four or more lines; “one word” and “circle” variants) than in Japanese, where similar efforts would perhaps be seen as something else altogether, and the haiku movement as a whole seems more inclined toward evolutionary (rather than revolutionary) change. Even as rules are broken and outgrown, they persist in ensuing works as contrarian presences, tangible arbiters of form.

In these Sanki translations, I did not adhere to the 5-7-5 rule or the native order of the haiku. These versions therefore consist of novel arrangements of verses more or less faithfully rendered from the originals. Another aesthetic conceit that I assumed was that each haiku would have a discrete appearance on the page, much like the logograms of written Japanese; in their overall display, I was aiming for organic patterns, not neat compartments. Lastly, the italicized words that loom in places between haiku, while not in the original, were lifted from the haiku themselves and act like synapses, or the walls of an echo chamber, singled out because they recur, as thoughts do in a brain, or simply because musically they worked as a segue into the next scene.

Published on February 13, 2018