What We Didn’t Talk About When We Didn’t Talk About Ruth

by Jonathan Weinert

An instant suffices to disturb and annihilate

that supposed wisdom of which you are so proud.

—Michel Foucault

April 1966. My sister Ruth fell, her legs splayed out, one toward the railing, one along the length of the upstairs hallway, rag-dolled. I stood on the stairs’ second landing seeing everything as if it were happening in another time, or not in time, my mouth hanging open, helpless. I was seven and a sunlit season was passing. I loved Miss Shannon, my pretty red-haired glasses-wearing second-grade teacher, who let me read the advanced reading cards, the ones with the sky-blue identifying tabs along the top, because I was a special reader. I was a special boy in her class, but here with Ruth down on her side I was useless, and my parents were useless, running back and forth with no time to comfort or explain.

Ruth sprawled along the floor, her light blue skirt with the bow at the small of the back and her dark curled hair and her two bare legs ending in the two white bobby socks with light blue piping around the ankles and the two black patent leather shoes that shone for nothing now her legs had failed.

“I can’t walk!” Ruth shrieked, crying hot loud tears. “I can’t walk! I can’t walk!”

Mom crouched beside her, soothing, down on one knee but not touching, perhaps afraid to damage her. Dad stood off to one side, somber-faced and not involved. Something had gone wrong and nothing was making it better.

An ambulance arrived and a stretcher.

At Boston Children’s Hospital, where Ruth had been taken, the doctors performed a spinal tap. After several days the tests came back: they’d found a marker.

“Your sister has Guillain-Barré syndrome,” Mom said. “So that’s the story.”

Mom sounded irritated, as if Ruth’s illness were a personal affront. She clearly didn’t want to talk about it, but I had a few questions, beginning with whatever the thing was called. Did Mom say “Guillaume”? We had a Guillaume in our second grade class, fresh from Québec, so I knew the name; we called him Guy, to rhyme with “pie.” And then—beret? I pictured a French accordion player in a horizontally striped shirt, a cigarette dangling from his lower lip, and a monkey on a chain.

“She has …. What does she have?”

“Don’t ask. All I know is it’s rare.” Mom freighted this declaration with a truckload of grievance.

Rare was a frightening word, as was Ruth’s lengthy absence. Frightening too, was the sense of taboo that had gathered, like a cloud or a darkness, around the subject of Ruth’s well-being. My parents avoided addressing her illness directly, but the fact that no information was forthcoming only made it worse.

We visited Ruth at the hospital, on an open ward with about ten beds, like the one in Curious George Goes to the Hospital. The nurses wore starched white uniforms and white stockings and short white caps made of hard linen, some with one or two thin black stripes along the sides.

Ruth had made friends with a girl called Mindy, who had a problem with her heart. The weather had turned warm, so we wheeled Mindy and Ruth out into the little outdoor garden in the hospital’s inner courtyard. I brought a real film camera that I had been given for my birthday—a Brownie 127 with film that came in a bright yellow cardboard box. I photographed the walkways covered in crushed stone, the latticework with grown-over vines for shade, stone frogs half-hidden in the ivy. I photographed Ruth just once, slouching in her wheelchair, dark-complexioned and tragic, like an American Anne Frank.

Was Ruth in pain? Would there be lingering effects? Why had she become infected in the first place? Such questions were never discussed, and I don’t remember ever asking. We didn’t talk about a lot of things in my family, and the thing we didn’t talk about the most was Ruth.

*

I can no longer remember how long Ruth stayed in the hospital, whether it was weeks or months, but it felt like forever. By the time she returned home, the whole world had changed.

One casualty of Ruth’s illness was the loss of her exceptional musical skills. Precocious musical ability famously comes from nowhere and often announces itself early. Ruth was no Mozart, but she had music in her sinews, and it found its way out of her via the felted hammers and tensioned wires of the piano. Ruth learned on an old upright tucked into an alcove at the far end of the den—and when I say learned, I mean played. For all I could tell, she had the Bach Partitas and Satie’s Gymnopédies from birth. After the Guillain-Barré, however, some fractional lag in her fingers’ ability to respond to her brain made short work of her dexterity and touch, and the piano went silent.

Mom had been keeping watch over Ruth’s burgeoning musical ability with the gimlet-eyed intensity of a prison warden for a couple of years already. If Mom had failed in her ambition to become a painter, then Ruth would redeem that loss with her triumphs on the piano. To this end, Mom had enrolled Ruth, at the advanced age of six, in the music school at Dana Hall, the private school where Dad taught math. There she learned technique from one Denny Bacon, famous the country over, Mom often said, as a musical pedagogue and shaper of exceptional young talents.

Ruth had done brilliantly. After only two years of study, she was rewarded with a solo recital at the music school’s cavernous Bardwell Auditorium on a frigid night in January 1966. The venue was a short couple of blocks down the hill from our house, so we bundled up and strolled over with our hands in our pockets and our white breath smoking in the moonlight. Ruth made her way through a set list that included Bach’s Two-Part Invention No. 1 in C major and Mozart’s famous Piano Sonata No. 16 in three movements, along with a selection of short pieces by Debussy and an étude by someone named Kahlmann.

Three months later, she was in the hospital.

A framed black-and-white photo dated the week before the recital shows Ruth seated at the upright in a pinafore dress, the erstwhile Bacon bending proprietarily above her and looking, it always strikes me, a little Julia Childish, with her white ruffled blouse and stylish half-glasses on a metal chain. A curtained window lets in a blur of afternoon light. Immediately above Ruth’s head, a quirk of shadow paints the window sash a vivid black, blacker even than Ruth’s hair. It’s hard not to see this inky bar now as a minus sign or a premonition, some sort of apparition portending a calamity, like the dead faces that peer out from the backgrounds of spirit photographs.

The Guillain-Barré stood at the head of a series of health catastrophes, one after the other—physical, then mental, then emotional, then all three. If we had known how to interpret the omens then, we might have been prepared, at least a little, for the darkness that was coming.

*

Ruth had never been especially interested in being my playmate, but as she convalesced, she made some use of me. In the world according to Ruth, play was an exercise of power—her power. In that way, I was a good fit: I was available, I was two years her junior, and I could be counted on to obey.

One afternoon in the August of her hospital year, when it was too hot and humid to play outside, Ruth pulled out her Ouija board. This “Mystifying Oracle,” as it described itself on the box, consisted of a pale green glow-in-the-dark planchette and a board displaying a phosphorescent alphabet, a Yes and a No, and the digits 0 through 9. On Ruth’s command, we lowered the bedroom shades, huddled together on the floor, and rested the index fingers of our right hands on either side of the planchette.

“Don’t try to move it,” Ruth warned.“It’ll move once we make contact.”

Ruth shut her eyes and tilted her head back theatrically. “I’m feeling something! Are you? Are you feeling anything?”

“I guess so, yeah,” I replied, a little doubtfully. I wasn’t sure I wanted to. Ruth twitched but kept her eyes shut.

“Someone’s here!” she hissed, through clenched teeth.

The planchette shuddered and started gliding across the board. Ruth slowly read out the words as the luminous wedge pointed them out, one letter at a time.

“I … am … from … the … dead,” Ruth intoned, using her “mysterious” voice. “My … name … is … Len … and … I… am … in … hell!”

Len, the Ouija board revealed, had been a crop farmer in the mid-eighteenth century, in the Massachusetts township that later became the Boston suburb in which we lived. Len had been trampled to death by his horses, which he mistreated, and a farmhand had found his mangled body half-buried in the unplanted furrows of his back field.

I was not permitted to speak during these sessions, so the story came entirely out of Ruth’s mouth—or through her mouth, as she insisted. With Ruth in charge, the board tended to channel tales profuse with retribution and gore. Len’s story, gruesome enough to begin with, went on to comprehend some business with a murdered child and a bleeding cerebellum impaled on a hunting knife.

“I … did… these … things … for … Ramses!”

Len had apparently been possessed by the evil spirit of that ancient pharaoh and had had no choice but to do his bidding. I knew how Len must have felt. Ruth led me through the maze of the story as imperious as a queen.

Eventually, Len drifted off, called back to whatever shadowland he had come from by virtue of laws we could neither control nor comprehend, and Ruth ordered the window shades raised. The world outside looked strange—dimmed a little by the shadows of Ruth’s dark imagination. The sun hung low and gold and sinister, illuminating both those things I knew and could understand and other, malevolent things the existence of which I could no longer deny.

*

Playtimes with Ruth were not always so macabre, but they were always intense, even when the program called for something as lighthearted as dancing.

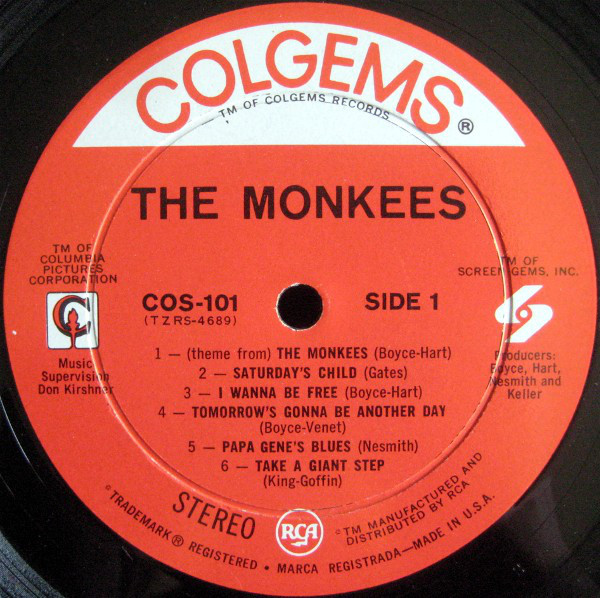

In a moment of rare agreement, Ruth and I had both fallen in love with The Monkees, which Ruth had received as a Hanukkah present the previous December. Over the winter, the disc, with its bright red Colgems label, often made its way onto the family turntable, and we would transform the den into a version of American Bandstand so that we could shimmy along to it.

Before we could drop the needle and have at it, though, Ruth demanded that we festoon the den with Spirograph drawings, the overlapping convolutions of which suggested a tame psychedelia. The prep work often took hours. Her monomaniacal commitment to the perfectly turned-out spiral made me want to weep with vexation and admiration. Many drawings marred by slips of the pen or the gnashing of the Spirograph’s interlocking teeth went into the trash before we produced a set that Ruth deemed perfect enough to tape up on the walls.

Younger brother, henchman, gofer: I was naturally inclined to follow, and Ruth was naturally inclined to lead. We would dance to The Monkees because Ruth said so. There must be perfect Spirograph drawings on the walls.

Weak but healing, Ruth was not herself yet perfect, and her legs did not yet seamlessly respond to signals from her brain. While I performed the Twist, or some defective variation learned from watching Chubby Checker on Shindig!, Ruth attempted the Mashed Potato. After a couple of songs, all the pivoting of feet and the shifting of weight from one leg to the other got the better of her, and she sidelined herself, as she watched me trying to keep time with “Last Train to Clarksville.” Breathing hard and pinch-browed, she leaned a little to the left because she couldn’t yet fully extend her right leg.

Just then, Mom swept into the room with an apron on and dish-soapy hands and turned the volume on the stereo down without saying a word. Her face was an eloquent treatise on the subject of displeasure. If I had had a similar expression on my face, she would have accused me of having a “mad on”—her phrase for dismissing whatever exasperation I happened to be experiencing at any given moment.

Mom started to leave but then stopped mid-stride, turned, and came back toward us fast. We froze. She grabbed Ruth’s right arm and yanked it down hard.

“Goddamn it, you, stand up straight!” she hissed.

Then she turned on her heel and strode from the room.

*

July 1967: the Summer of Love. The Flower Children went to San Francisco, and Benjamin arrived at the Lying-in.

Eight years my junior, and ten years younger than Ruth, Benjamin surprised us all. Mom laid him on a blue rayon blanket on the floor of the den. I crouched over him. He smiled, he cried: my baby brother. Odd new objects began appearing in the house: a white Rubbermaid bucket full of stink, safety pins with yellow plastic ducks on the ends. The Dydee Diaper truck came and went.

I spent a fair amount of time alone for the first few months after Benjamin’s birth, often tracing out maps from the big world atlas in the den. With the radio tuned to my beloved WRKO, I jumped up and down on my bed and played tennis racquet air guitar: “Fakin’ It,” “Never My Love,” “Summer Rain”—any song with a minor swerve and a strong melody.

Mom was solicitous of baby Benjamin—gentle and careful and even patient—although my presence still seemed to aggravate her as much as it ever had. Dad was more absent than usual, if that was possible, taking on additional patients at his optometry practice in the late afternoons. Maybe he needed to escape, or maybe he simply had to make extra money to pay for the diaper service, the formula, and the dozens of other expenses a new baby entails.

By the end of the summer, Benjamin had replaced Ruth as the single focus of Mom’s attention. This did not sit well with Ruth, and she mounted a counterinsurgency. She threw tantrums, bashed the piano keys when Benjamin was supposed to be down for a nap, and shut herself up in her room and sulked. Not only did her outbursts become more frequent, they also became more belligerent.

I invited a new friend, Mark, a kid I liked and wanted to impress, over one afternoon. Everything went along well at first, but I hadn’t accounted for Ruth’s need to terrorize. After we’d been playing together for an hour or so, Mark went into the half bathroom under the front hall stairs for a post-lemonade pee, and Ruth locked him in. (Why there was a lock on the outside of the bathroom door I couldn’t say.) The locking mechanism jammed, or we didn’t have a key, and Mark was stuck inside, increasingly frantic and embarrassed. Eventually, he got free by removing the bathroom window screen, shimmying through the narrow opening, and dropping down into the backyard flower bed below.

Mark brushed himself off and had a few quiet words with Mom. Mark’s mother arrived soon after to collect him, and he never came back.

*

I spent a lot of time outside that summer, where I could escape the complications of life in a house with a new baby. I devoted many hours to the little waterfall on Fuller Brook, a tributary of the famous Charles River, which I could reach by climbing down a concrete embankment where the channel had been sheathed to deter erosion. I never tired of throwing little sticks into the watercourse above the falls and watching to see where the action of the spilling water would carry them—far downstream and under the Grove Street overpass, or off to the sides where they would get held up in the eddies. Vortex was a good word, and it pleased me, although I found the prospect of being trapped in an endless revolution disconcerting. I threw rocks at the spinning sticks to dislodge them.

One heat-stunned afternoon, I surprised a crayfish out of the water on the ledge at the top of the waterfall. Like a miniature brown lobster with electric blue decorations, the little creature reared up on his hindmost legs, brandishing two open claws. He was absurd, this candy-bar-sized fellow, challenging a being several orders of magnitude larger than himself; I could have crushed him under one foot. I admired his courage, the defiant shine of his lidless black eyes. I even envied his life a little, in which only the occasional stupid human would come along to disturb the untroubled flow of his experiences.

How, I often wondered afterwards, did I appear to him? Did he envy me—my size, my mobility, my intelligence? What, on the other hand, would the world look like if I could see the way a crayfish sees?

*

If 1967 was the Summer of Love, 1968 was the Summer of Madness.

The year’s “seismic tidings,” as Christopher Hitchens once put it, started convulsing the landscape well before the hot weather came in. The Tet Offensive, the bloodiest phase of the Vietnam War, began at the end of January, and news of the conflict began invading our house on a regular basis: the grim Boston Globe headlines, the growing casualty counts on the CBS Nightly News with Walter Cronkite, graphic films and stills from the era’s embedded reporters. The escalation of hostilities on the other side of the world coincided with my growing awareness of events outside of suburbia’s privileged bubble. I became aware, in a less distant and abstract way than before, that something terrible was going on, that college kids and grownups had been protesting, that President Johnson had become a target of widespread loathing, and that Black people were smashing windows and torching cars in cities across the country. By June, riots had broken out in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. “All You Need Is Love,” the Beatles’ number one single had assured us the summer before, but by 1968 there didn’t seem to be enough of it to go around.

My parents barely noted the April murder of Martin Luther King Jr., but then Robert Kennedy was assassinated in June, on my ninth birthday. Mom and Dad had been closely following “our Bobby’s” progress through the presidential primaries. He was their latest, fondest hope—a local boy made good, like his older brother John Fitzgerald—and when he won the California primary he appeared to be on the cusp of redeeming the country from the horror of his brother’s assassination five years earlier. (I remembered that day, too, with the TV strangely on in the middle of the afternoon and Mom in tears.) But that was not to be.

In the days following Bobby’s killing, we watched the confusing reports of the scene at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles over and over, as the news shows kept replaying it: the crowd first cheering, then panicking; photos of a dying Kennedy on his back in the hotel kitchen, with a white-jacketed busboy kneeling beside him; alleged shooter Sirhan Sirhan in handcuffs; the shocked voices of the reporters.

“What I think is quite cleahh is that we can work together in the lahst analysis,” Kennedy announced in his acceptance speech, showcasing the exaggerated Boston accent that so pleased my parents. “We ahh a great country, an unselfish country, and a compassionate country, and I intend to make that my basis for running over the period of the next weeks. So thanks to all of you and now it’s on to Chicago and let’s win thayah!”

The crowd erupted in chants of “We want Bobby! We want Bobby!” Less than five minutes later, shots were fired.

Los Angeles radio reporter Andrew West, who had just asked Kennedy a question and was standing nearby, broadcast from the scene.

“Senator Kennedy has been sh—Senator Kennedy has been shot! Is that possible? Is that possible? It’s been—is it possible, ladies and gentlemen? It is possible he has—not only Senator Kennedy—oh my God. Senator Kennedy has been shot, and another man, a Kennedy campaign manager, and possibly shot in the head.”

You could hear the shock in West’s voice, and in his barely coherent commentary. It was the end of the dream of a less divisive, less violent nation.

Twenty-four hours after West’s broadcast, Bobby Kennedy was dead. My parents shifted their presidential hopes to Democratic frontrunner Hubert Humphrey, but he proved unequal to the task, gaining the Democratic nomination but losing the election by a landslide. Enter Nixon and five more years of war. Enter the Dirty Tricksters and the White House Plumbers. Enter Watergate.

*

Seismic events were convulsing our household in 1968, too, as if to mirror the dreadful episodes taking place outside of it.

Ruth had almost fully recovered from the Guillain-Barré by the end of winter, but in the spring, when she was about to turn eleven, she started screaming. Memory notoriously plays us for fools and dupes, and I’m certain that I remember this incorrectly, but it seemed to me as though some hidden switch had been flipped. One day Ruth was Ruth, as complicated and high-strung and peremptory as ever. The next day she was snarling and unrecognizable.

Events could not in fact have unfolded this way. As I learned later, from firsthand experience, there exists no absolute borderline between madness and sanity, no universally recognized demarcation between emotional health and whatever its opposite is supposed to be. Theorists on mental illness from Michel Foucault on down have emphasized spectrum and context over definition and diagnosis. Human behavior extends over a large and paradoxical range, and it makes sense to avoid judgment and to take care not to stigmatize that which you don’t immediately understand. But there is a dark side to making the frontier between “normal” and “abnormal” porous and equivocal. As a boy with serious doubts about himself and an active imagination, I often wondered if I had passed from the one condition to the other, and exactly when I had done so, and if I had in fact entered a shadow world, whether I would ever be able to come back.

Over the course of the year, the intensity of Ruth’s temper tantrums ratcheted up, their ferocity and duration approaching hurricane force. There was a new eccentricity and stridency in Ruth’s outbursts that bordered on psychosis, then crossed that border. She would become inconsolable, her eyes fear-wide and glittering. She obsessed over disturbing surmises, saw more and more things that were not in fact there.

One afternoon after school Ruth confronted me in the upstairs hallway, blocking the doorway into my room.

“Did you go in my room?” she demanded. “No, I—”

“You went into my room and now some things are missing!” she shouted, her voice rising to a shriek. “You stole my favorite pillow!”

I gaped.

“You better put my stuff back! Now get away from me! You’re poisoning my atmosphere!”

Off she stalked, stiff-armed and rigid, like a human tree, but then she suddenly about-faced and came stalking back.

“You’ve been lying to Jill about me, haven’t you?” she screamed, her face three inches from mine. Jill was Ruth’s best friend, and my stocky standby friend Tim’s older sister. “You and Jill have been saying terrible things about me!”

I stared at this alien, murderous being and felt … well, to be honest, I felt nothing. Or, to put it another way, I felt nothingness rising up from its kingdom deep within the earth and planting its symptom in my solar plexus.

“Stop spying on me! Stop using up all my air!”

Scenes like this repeated, with variations, throughout the following months. Mom kept her distance, preferring denial to intervention. On the rare occasions when he was around, Dad would speak to Ruth in a low, quiet voice, trying to talk her down. She would stop shouting, but she continued to look daggers at me whenever our paths crossed.

Ruth’s violence and unpredictability put the family on a war footing, like America itself. Anything could set Ruth off, or nothing. We moved through invisible shrapnel and damage, as if a bomb had been detonated inside the house. But despite the considerable wreckage, the usual taboos remained in force: if you took care not to acknowledge something or reference it, you could pretend that it didn’t exist. The silence was almost as terrific as the explosion itself.

*

Diagnosis: schizophrenia. In the late 1960s, this meant antipsychotics, institutionalization, and blame.

Soon after the first episodes and the hint of something intractable waxing in her, Ruth had consultations, initially with Dr. Pfeiffer, the family pediatrician, and then with a growing collection of increasingly specialized specialists. She went in and out of various Boston hospitals for observation over a period of about three years. Repeated outbursts at home and a few public displays of rage and cartoonishly lascivious confrontations with assorted neighbors and second cousins earned her several brief stints in the locked adolescent ward of the Westborough State Mental Hospital, a Gothic pile about thirty miles west of us, complete with white-uniformed attendants and bleary-eyed inmates sliding along the corridor walls and moaning theatrically into space.

Ruth acquired a team of psychiatrists and counselors, a shadow crowd that monitored her behavior from their offices at Children’s Hospital and elsewhere in Boston’s medical-industrial complex. This crew was responsible for keeping the pace of Ruth’s delusions and paranoia just this side of psychic escape velocity. Prescriptions were filled, diagnoses were written, appeals to the latest theories were made. Ruth was dosed with chlorpromazine, and because the fashion of the day was family dynamics, the team called us all in for a summit.

As mausoleums go, the Children’s Hospital conference room wasn’t so bad. Hoisted four or five stories in the air, it was a charnel house with a view, a vault with a large rectangular table instead of a marble slab. As in any charnel house, its attendants ministered to the dead—the dead selves the psychologically wounded drag around with them in their living bodies, like sacks of weights.

We shuffled in, Mom, Dad, Ruth, and I, a little cowed by the circumstances and the size of the room. The psychiatrists and psychologists and pharmacologists and social workers ranged around the table had been schooled in the varieties of psychic and emotional erasure, and they were ready to school us. They had marshaled their surmises, prepared the phrases that would, like magical formulae, render clear and visible the malign powers that were eradicating Ruth’s capacity to remain herself.

Grass light shivered in the windows, a gray glow shot through with transparent green. Early spring: a transitional season, damp and ravaged and leafless. Overhead went a layer of gunmetal cloud, meticulously featureless, like a Civil War camp blanket stretched tight.

I felt wrongness in the room, a wrongness among the strangers confronting us. Ruth had been colonized by wrongness too, but this was a different and treacherous kind of wrongness: the kind that believed itself to be right.

The team around the conference table greeted us with professional blank faces and mirthless smiles. Although we were officially there to get answers, I felt like we were on trial. We sat on one side of the table and the six of them, sepulchral and not yet introduced, sat on the other. I didn’t understand the nature of the supposed exchange. Dad put his infuriating bland face on, and Mom the quizzical expression that she sometimes assumed with strangers when she was nervous: drawn-on eyebrows held tightly and acutely aloft, as if she were constantly asking a question or agreeing with some unspoken assertion. Ruth had caved in behind her scowl, her brows so furiously knit that they almost touched. I felt hot and vague, the way I felt when I thought I had done something wrong but didn’t know what it was. I couldn’t sit still, and my chair kept slewing sideways on its casters.

“Dr. and Mrs. Weinert,” intoned a small, dark, unsmiling woman with severely pulled-back hair and glasses on the end of her nose. “I am Dr. Feinbaum, the psychiatrist leading the team assigned to Ruth’s case. Thank you for coming in today.”

Dr. Feinbaum managed to make “Thank you” sound like “It’s the least you could have done and let’s face it, we all know it isn’t nearly enough.” A thick green file folder—Ruth’s medical history?—lay open on the table in front of her.

“And this is?” Dr. Feinbaum asked, turning toward me.

“This is our son, Jonathan,” Dad replied, employing his sober optometrical tone.

“Jonathan. Yes,” Dr. Feinbaum said, giving me a look over the top of her glasses.

She turned her gaze to the papers on the table in front of her.

“This is the team,” she said, gesturing indefinitely and not looking up.“Miss Scanlon, our staff counselor, Dr. Orhan, a psychologist on loan from Beth Israel, and Dr. Lenz, a psychopharmacologist.” Dr. Feinbaum failed to introduce the other two team members, a stoop-shouldered little old man with a wrecked face, and a youngish professional-looking woman in a dark blue suit—legal counsel?

“We have been observing Ruth and discussing her condition and we thought it best to bring the family in for a consultation.”

Dr. Feinbaum employed an unmistakable tone of rebuke. We were silent. She eyed us all over the top of her glasses, then referred again to the open file.

“In cases where the etiology of a mental illness indicates family dynamics”—another look over the top of her glasses—“we believe that the family should be present to hear our determinations and our recommendations for treatment.”

Mom shifted in her seat and raised her eyebrows an increment higher. “Well. Family dynamics!” she repeated, trying to put some brightness in her voice. She smiled.

“Yes, family dynamics,” Miss Scanlon cut in. She curled the ends of her long gray hair around the first two fingers of her right hand as she spoke. “In our review of the patient’s home life and circumstances, we have concluded that parental offenses and derelictions have contributed to, if not caused, emotional dysregulation and early onset psychosis.”

“Specifically, and technically,” Dr. Feinbaum continued, “Mrs. Weinert fills the role of what we term a schizophrenogenic mother. She has created a profoundly distorted and distorting family milieu which has resulted in the patient’s extreme emotional distress and schizoaffective episodes.”

A long pause.

“Are you saying that Ruth’s illness is Lois’s fault?” asked Dad, in a level voice.

Dr. Feinbaum and Miss Scanlon exchanged looks. “To be blunt, yes,” Miss Scanlon said.

Another silence.

“Let me be clear,” Miss Scanlon went on, addressing Dad. “Based on our assessment of Ruth, and based on our prior interviews of you and Mrs. Weinert, we agree that this is a family dynamic. Because you have failed to challenge the delusional ideas of your wife, these concepts have created a reality within the family. This reality is a kind of shared madness—a family madness, if you will.”

“What do you mean by ‘delusional ideas’?” Dad asked.

“Fluid self-boundaries, the compulsion to impose her view of the world on those around her, imperviousness to the needs and wishes of others.”

Miss Scanlon paused. “I could go on.”

“It’s always the mother, isn’t it,” Mom said finally.

“It’s both of you,” Dr. Feinbaum rejoined, looking from Mom to Dad and back again. “In fact, it’s all of you.”

Another long pause.

“Well, I can’t go along with that analysis,” Dad said, maintaining his equanimity. But he was firm.

Pride for my father surged. In his mild and unassuming way, he had broken out of his habitual mode of detachment, at least for a moment, and gave voice to the objections we all were feeling.

As startling and refreshing as this breakthrough was, though, his one statement represented the extent of the pushback. Nowadays we arrive in consultation rooms, often to our doctors’ frustration, armed with theories and self-diagnoses courtesy of WebMD and other less reputable online sources: we expect discussion, explanation, and collaboration. Back then, all of the powerful shoes were on the doctors’ feet. They were the authorities, and we knew nothing. We were not expected, and not welcome, to argue. Doctors wielded a sort of military prerogative, and questioning was regarded as a form of insubordination.

Not that my parents were liable to question much in any case. Before the meeting chaired by the baleful Dr. Feinbaum had even adjourned, my parents had already vectored their efforts in the direction of clamming up. I could feel the diversion of their powers in the room’s atmosphere, like a sudden shift in the weather.

This was a profoundly perplexing moment for me. I couldn’t argue with the doctors’ assessment of Mom’s behavior, to the extent that I could understand it, or what they may well have referred to among themselves as her pathology, although I had never arrived at anything resembling the phrases they employed to describe them, so clinical and specific. On the other hand, I sided with Dad, as what son would not when he finds his family suddenly assailed by impertinent strangers? I had good reasons for my deep and largely inarticulable misgivings about life at home, but nothing encourages solidarity like an enemy assault.

Like Dad, I couldn’t accept the view that my parents were responsible for Ruth’s psychosis. Even if it was partly true, it was false in the way that the doctors expressed it, flinging it in our faces like an indictment, and it was false to the extent that it failed to account for other possible causes. Wasn’t Ruth at least in part responsible for her own behavior? After all, she was no ventriloquist’s dummy. Did my parents force her to scream at me? And what about simple accident? Children fell ill, snapped limbs, or drowned swimming in lakes. Shit happened, and the reasons why, if any such reasons existed, did not always follow from the most obvious of presumed causes.

Later, after we got home, my thinking turned darker. Hadn’t the doctors implied that I was also part of the problem? Wasn’t I an integral part of the so-called family dynamic? Maybe Ruth’s illness was partly my fault. After all, she kept insisting that it was. I had been well schooled in the view that something was fundamentally wrong with me, so it was a small step to feeling responsible. But I felt responsible without being able to identify the nature or extent of my responsibility. I felt the urge to apologize—but to whom, and for what? I concluded, in my illogical, childish way, that I owed the world an apology simply for being in it.

*

As hard as it may be to credit now, psychogenic theories of schizophrenia were the last diagnostic word when Ruth first became symptomatic. German psychoanalyst Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, who had emigrated to the United States during World War II to escape the Nazis, promoted the theory of the schizophrenogenic mother in the late 1940s. In Fromm-Reichmann’s view, psychosis often developed in the presence of a rejecting, domineering mother who alienated her children and placed intolerable stress upon the family. In the 1950s, researchers in the Adult Psychiatry Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health argued that families amplified the damage with the pretense of a nonexistent domestic harmony. “Family dynamics” referred to the entire family’s participation in a web of denial and lies, but the cold, unfeeling mother was at the heart of it, like a presiding spider. In the mid-1960s, well before we arrived at the Children’s Hospital conference room, the theory of the schizophrenogenic mother had become an almost unquestioned element of the psychiatric orthodoxy. In her assignment of familial wrongdoing and blame, Miss Scanlon was simply hewing to the party line.

Many in the psychiatric community would later look back with horror at the schizophrenogenic heyday, just as many psychiatrists of that time looked back with horror at the earlier era of mass institutionalization and routine surgery.

Lobotomy had been the gold standard for treating schizophrenia before the advent of antipsychotic drugs, and tens of thousands were performed in the United States alone in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. You drilled a hole in the patient’s skull, injected the frontal lobes with ethanol, inserted a loop of wire into the brain to create a circular wound in the offending region, drove what was essentially an ice pick through a patient’s eye sockets with a hammer, then jiggled it around in there to separate the frontal lobes from the rest of the brain. Side effects included vomiting, incontinence, paralysis, apathy, lethargy, loss of speech, and severe cognitive impairment. Lobotomy had had its critics, to be sure, but they were barely audible over the groundswell of acclaim: the 1949 Nobel Prize in Medicine went to the neurologist who invented the procedure.

The schizophrenogenic interpretations that followed were being made well into the 1980s, when they gave way to biogenetic views, which imagined schizophrenia to be a brain disorder, the consequence of unfavorable biochemistry and suspect neural anatomy. Psychogenic theories—the schizophrenogenic mother among them—fell out of favor and were eventually discredited, but only after their indiscriminate application had caused much appalling torment and pain. Families like ours who were unfortunate enough to require professional intervention during the psychogenic era were liable to be destroyed twice: once from within by means of the illness and once from without by means of the cure.

*

The story doesn’t have a happy ending, or really any kind of ending at all. The psychiatrists in charge of Ruth’s brain chemistry fumbled with various combinations of antidepressants and antipsychotics over the years, with mixed results. At times Ruth didn’t take her medications at all, and the hallucinations and paranoia would return with a vengeance, often ending in hospitalizations or run-ins with the local police. I couldn’t entirely blame her for these lapses, as the drugs made her listless and vacant-eyed and wreaked havoc with her metabolism and sleep. Eventually, Ruth developed an eating disorder. She stopped joining the family for dinner (a small mercy), sometimes sneaking down to the kitchen in the middle of the night to gorge. More often, she would starve herself, dropping alarming quantities of weight.

Despite attending only about a quarter of her senior year, Ruth somehow managed to finish high school near the top of her class. My parents derived hope. There were a few bright stretches in the years following graduation—a semester at the University of Southern California to study film, the occasional return to piano playing, an apartment in Boston and a series of part-time jobs—but the trend was decidedly down. Repeated institutionalizations gave way to a prolonged sojourn in an assisted-living facility and then to a permanent residency in a halfway house. Mom and Dad were either not able or didn’t know how to support Ruth financially, so she at length became, in the Orwellian phrase, a ward of the state.

Ruth had less and less to do with me over the years, and she made it abundantly clear that she wanted it that way. After our parents passed away in the early 2000s, I lost contact with her almost entirely. It was as if she had died too, but there was no event, no funeral, no observance to mark her disappearance. It was as if a planet had slipped out of the solar system, but so slowly and so silently that nobody seemed to notice, and nobody said a word.

Published on May 8, 2023

First published in Harvard Review 60