Contributor Bio

Alex Ankai and Andrew Koenig and Cecilia Weddell and Chloe Garcia Roberts and Christina Thompson and Gabrielle McClellan and Jordan Taliha McDonald and Major Jackson and Maria Marchinkoski and Ophelia John and Yasmin Tayeby

More Online by Alex Ankai, Andrew Koenig, Cecilia Weddell, Chloe Garcia Roberts, Christina Thompson, Gabrielle McClellan, Jordan Taliha McDonald, Major Jackson, Maria Marchinkoski, Ophelia John, Yasmin Tayeby

What We’re Reading

by the Staff at Harvard Review

As you might guess, we’re big readers at Harvard Review. From histories to YA fantasy series, from beloved novels to the latest poetry releases—our staff reads it all. Here’s a taste of what we’ve been dipping into this past year.

Christina Thompson, Editor

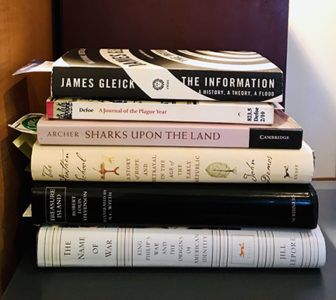

A lot of my reading these days is related to the history of epidemics—as a way, I suppose, of understanding the times we live in. To that end, I’ve been reading Daniel Defoe’s lively A Journal of the Plague Year, which purports to be an eyewitness account of the London plague of 1665 but was actually published in 1722, as well as Seth Archer’s Sharks Upon the Land (Cambridge University Press, 2018), a wonderfully researched history of the impact of disease on nineteenth-century Hawaii. For a different project, I picked up Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) and, lo, Defoe cropped up again! Stevenson’s primary source for pirate lore was A General History of the Pyrates (1724), ostensibly authored by one Captain Charles Johnson but written in fact by the astonishingly prolific Defoe. Incredibly, the true authorship of this classic was not determined until 1932. I also read a couple of early American histories: Jill Lepore’s The Name of War (Knopf, 1998) and John Demos’s The Heathen School (Knopf, 2014), both fascinating stories wonderfully well told. And I started, though I may never finish, James Gleick’s The Information (Vintage Books, 2012), an ambitious attempt to relate the entire history of communication—how we’ve stored and shared information over a span of thousands of years.

A lot of my reading these days is related to the history of epidemics—as a way, I suppose, of understanding the times we live in. To that end, I’ve been reading Daniel Defoe’s lively A Journal of the Plague Year, which purports to be an eyewitness account of the London plague of 1665 but was actually published in 1722, as well as Seth Archer’s Sharks Upon the Land (Cambridge University Press, 2018), a wonderfully researched history of the impact of disease on nineteenth-century Hawaii. For a different project, I picked up Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) and, lo, Defoe cropped up again! Stevenson’s primary source for pirate lore was A General History of the Pyrates (1724), ostensibly authored by one Captain Charles Johnson but written in fact by the astonishingly prolific Defoe. Incredibly, the true authorship of this classic was not determined until 1932. I also read a couple of early American histories: Jill Lepore’s The Name of War (Knopf, 1998) and John Demos’s The Heathen School (Knopf, 2014), both fascinating stories wonderfully well told. And I started, though I may never finish, James Gleick’s The Information (Vintage Books, 2012), an ambitious attempt to relate the entire history of communication—how we’ve stored and shared information over a span of thousands of years.

Chloe Garcia Roberts, Deputy Editor

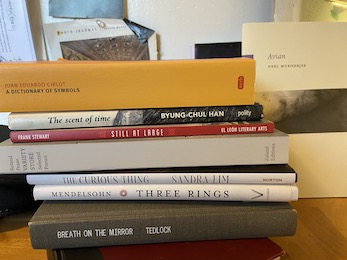

I’m a bit of a fitful reader these days, enjoying books that lend themselves to quick dives as opposed to those demanding protracted sojourns. Juan Eduardo Cirlot’s Dictionary of Symbols (New York Review Books, 2020; translated by Jack Sage and Valerie Miles) is a perfect book at the moment; tiny, concentrated entries that make me think all day. For example, did you know that “The musician is a common symbol of the fascination of death”? Neither did I. Daniel Mendelsohn’s Three Rings (University of Virginia Press, 2020) and Byung-Chul Han’s The Scent of Time (Polity, 2017; translated by Daniel Steuer) are both making me aware of the many ways of inhabiting time and speaking nicely to this period of years that feel like days, months that feel like years. Breath on the Mirror by Dennis Tedlock (1997) is just the latest in a deep dive into his various Mayan translations and writings. And finally, I am enjoying the intimacy of reading the work of friends both near and far: Sandra Lim’s The Curious Thing (W. W. Norton & Company, 2021), Neel Mukherjee’s Avian (Sylph Editions, 2020), Frank Stewart’s Still at Large (El León, 2022), and Roland Pease’s Variety Store (1990).

I’m a bit of a fitful reader these days, enjoying books that lend themselves to quick dives as opposed to those demanding protracted sojourns. Juan Eduardo Cirlot’s Dictionary of Symbols (New York Review Books, 2020; translated by Jack Sage and Valerie Miles) is a perfect book at the moment; tiny, concentrated entries that make me think all day. For example, did you know that “The musician is a common symbol of the fascination of death”? Neither did I. Daniel Mendelsohn’s Three Rings (University of Virginia Press, 2020) and Byung-Chul Han’s The Scent of Time (Polity, 2017; translated by Daniel Steuer) are both making me aware of the many ways of inhabiting time and speaking nicely to this period of years that feel like days, months that feel like years. Breath on the Mirror by Dennis Tedlock (1997) is just the latest in a deep dive into his various Mayan translations and writings. And finally, I am enjoying the intimacy of reading the work of friends both near and far: Sandra Lim’s The Curious Thing (W. W. Norton & Company, 2021), Neel Mukherjee’s Avian (Sylph Editions, 2020), Frank Stewart’s Still at Large (El León, 2022), and Roland Pease’s Variety Store (1990).

Major Jackson, Poetry Editor

At some point during the past year, I became haunted by the disturbing facial expressions in Francis Bacon’s work, particularly his screaming pope paintings which, I recently learned, took inspiration from a scene in Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin. The open-mouthed gasp captures for me the expression I read in the faces of many who are grappling with the daily challenges of living through a pandemic. The image also represents an evocative pause, a breaking point in any rational understanding of what the moment or the future portends. We do not hear the scream in Bacon’s paintings, just as we do not know the extent to which the global health crisis affects the lives of those around us—a silence as palpable as the exhaustion we feel. Among the books I read this year is Raymond Antrobus’s extraordinary collection The Perseverance (Penned in the Margins, 2018), which profoundly names his childhood and life as a deaf person, particularly “the difficulty of navigating sound in a hearing world.” The book allegorizes silence, invisibility, and most especially, listening. The books of poetry and essays I responded to most seem to feature listening as an urgent act of survival, specifically the lessons of history, art, and literature that might show us some way through our current anxiety.

At some point during the past year, I became haunted by the disturbing facial expressions in Francis Bacon’s work, particularly his screaming pope paintings which, I recently learned, took inspiration from a scene in Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin. The open-mouthed gasp captures for me the expression I read in the faces of many who are grappling with the daily challenges of living through a pandemic. The image also represents an evocative pause, a breaking point in any rational understanding of what the moment or the future portends. We do not hear the scream in Bacon’s paintings, just as we do not know the extent to which the global health crisis affects the lives of those around us—a silence as palpable as the exhaustion we feel. Among the books I read this year is Raymond Antrobus’s extraordinary collection The Perseverance (Penned in the Margins, 2018), which profoundly names his childhood and life as a deaf person, particularly “the difficulty of navigating sound in a hearing world.” The book allegorizes silence, invisibility, and most especially, listening. The books of poetry and essays I responded to most seem to feature listening as an urgent act of survival, specifically the lessons of history, art, and literature that might show us some way through our current anxiety.

Cecilia Weddell, Associate Editor

The book I’ve recommended the most over the past year is Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a beautifully engaging book that brings together indigenous knowledge and academic experience to show us the reciprocal (and, sometimes, strained) relationships that the Earth maintains with all its beings. I read Octavia Butler for the first time this year, eagerly “flipping” the pages of my e-reader throughout the three novels Kindred, Fledgling, and Parable of the Sower (1979, 2005, and 1993, respectively). In translation, I enjoyed the snappy pace and cleverness of Nona Fernández’s Space Invaders (translated by Natasha Wimmer for Graywolf Press, 2019), the echoey sparseness of Yuko Tsushima’s Territory of Light (translated by Geraldine Harcourt for Macmillan, 2020), and the huge range of voices in Granta’s second Best of Young Spanish-Language Novelists anthology (2021). A subscription to Creative Nonfiction has brought a fresh batch of essays to my mailbox every few months, and I found myself thinking back to Suzanne Roberts’s essay in their seventy-fifth issue for days and maybe even weeks after I read it.

The book I’ve recommended the most over the past year is Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass (Milkweed Editions, 2015), a beautifully engaging book that brings together indigenous knowledge and academic experience to show us the reciprocal (and, sometimes, strained) relationships that the Earth maintains with all its beings. I read Octavia Butler for the first time this year, eagerly “flipping” the pages of my e-reader throughout the three novels Kindred, Fledgling, and Parable of the Sower (1979, 2005, and 1993, respectively). In translation, I enjoyed the snappy pace and cleverness of Nona Fernández’s Space Invaders (translated by Natasha Wimmer for Graywolf Press, 2019), the echoey sparseness of Yuko Tsushima’s Territory of Light (translated by Geraldine Harcourt for Macmillan, 2020), and the huge range of voices in Granta’s second Best of Young Spanish-Language Novelists anthology (2021). A subscription to Creative Nonfiction has brought a fresh batch of essays to my mailbox every few months, and I found myself thinking back to Suzanne Roberts’s essay in their seventy-fifth issue for days and maybe even weeks after I read it.

Andrew Koenig, Book Review Editor

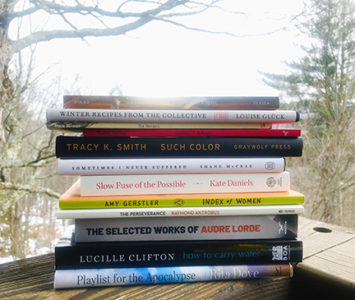

Less well known than her later work, Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight (1939) has stood me in good stead while waiting for buses, sitting in coffee shops, or killing time at bars—three activities much indulged in by Rhys’s restive, reckless narrator, who drifts from one Parisian café to another, one recollection and ill-fated love affair to the next. This is a novel about a febrile sense of desperation but full of humor and laser-sharp sentences that could’ve been written five minutes ago, though the novel is almost one hundred years old. “All of the people in this book are real,” Natalia Ginzburg writes in her preface to Family Lexicon (New York Review Books, 2017; translated by Jenny McPhee). For all its acerbity, Ginzburg’s is a compassionate family history worth reading for the punchlines alone: “It’s my bitch’s sister!” a schoolgirl says to Ginzburg’s mother about her pet dog; “In this house, you turn everything into a bordello,” her grandmother admonishes. Whether unpeeling the dynamics of a sibling rivalry or chronicling her father’s outbursts, Ginzburg is an eagle-eyed, fair-handed, and in McPhee’s translation, funny observer. Louise Glück’s newest poetry collection, Winter Recipes from the Collective (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), is short—clocking in at just forty-two pages—but packs a punch. Her first release since winning the Nobel Prize, Winter Recipes is of a piece with Glück’s earlier work and, at the same time, a departure. What has been called the “fabular” quality of these poems sets them apart as myths for a new millennium. The titular poem is about a quasi-mythical moss sandwich eaten in winter (“it was what you ate / when there was nothing else”); another is about a lost passport; a third about the art of bonsai. “I try and comfort you / but words are not the answer,” Glück writes, yet the grim pronouncement is balanced by a commitment to artistry and poetry’s capacity for consolation. “The book contains / only recipes for winter, when life is hard. In Spring, / anyone can make a fine meal.”

Maria Marchinkoski, Assistant Editor

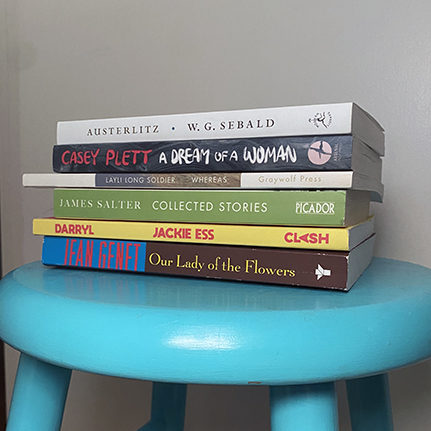

In fiction, I finally got around to reading W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz (Modern Library, 2001; translated by Anthea Bell). Teachers, friends, and mentors all insisted I read Sebald, so naturally, I put off reading him for a long time. When I started Austerlitz, I understood why everyone recommended him. The novel is partly about its title character: a child refugee who escaped Czechoslovakia for Britain during the Nazi occupation. Austerlitz becomes an architectural historian, and in his attempt to reconstruct the lost lives of his parents, exposes readers to descriptions, diagrams, and pictures of Europe’s many jails, libraries, courthouses, and concentration camps. The story—like the architecture—is more mazelike than logical. Sebald’s vision of the archive doesn’t clarify history; it obscures it. In poetry, I reread Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas (Graywolf Press, 2017). While the most famous parts of the collection revolve around the Congressional Resolution of Apology to Native Americans, Long Soldier is concerned foremost with language—its physical impact, its legal legacy, and its historical form. Long Soldier not only sees the dizzyingly different ways that language works, but she also makes those differences palpable. In short fiction, I’m currently reading Casey Plett’s A Dream of a Woman (Arsenal Pulp, 2021). I haven’t finished it yet, but I was floored by her 2018 novel Little Fish, about an ensemble of trans women living through one winter in Winnipeg.

In fiction, I finally got around to reading W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz (Modern Library, 2001; translated by Anthea Bell). Teachers, friends, and mentors all insisted I read Sebald, so naturally, I put off reading him for a long time. When I started Austerlitz, I understood why everyone recommended him. The novel is partly about its title character: a child refugee who escaped Czechoslovakia for Britain during the Nazi occupation. Austerlitz becomes an architectural historian, and in his attempt to reconstruct the lost lives of his parents, exposes readers to descriptions, diagrams, and pictures of Europe’s many jails, libraries, courthouses, and concentration camps. The story—like the architecture—is more mazelike than logical. Sebald’s vision of the archive doesn’t clarify history; it obscures it. In poetry, I reread Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas (Graywolf Press, 2017). While the most famous parts of the collection revolve around the Congressional Resolution of Apology to Native Americans, Long Soldier is concerned foremost with language—its physical impact, its legal legacy, and its historical form. Long Soldier not only sees the dizzyingly different ways that language works, but she also makes those differences palpable. In short fiction, I’m currently reading Casey Plett’s A Dream of a Woman (Arsenal Pulp, 2021). I haven’t finished it yet, but I was floored by her 2018 novel Little Fish, about an ensemble of trans women living through one winter in Winnipeg.

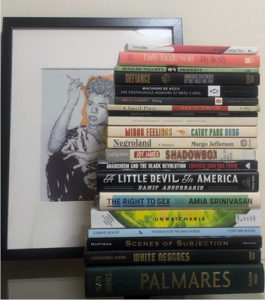

Jordan Taliha McDonald, Assistant Editor

This year, I read many books for the first time and continued a ritual of rereading of a few of my favorite works. Of those that were new to me, the republication of Anarchism and the Black Revolution by Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin (Pluto Press, 2021), A Little Devil in America by Hanif Abdurraqib (Random House, 2021), Shadowboxing by Joy James (1999), The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), and My Body by Emily Ratajkowski (Metropolitan Books, 2021) still weigh on my mind. The works I continue to revisit, Negroland by Margo Jefferson (Vintage, 2016), Passing by Nella Larsen (1929), A Small Place by Jamaica Kincaid (1988), White Negroes by Lauren Michele Jackson (Beacon Press, 2020), Fantasia for the Man in Blue by Tommye Blount (Four Way Books, 2020), and Scenes of Subjection by Saidiya Hartman (1997) gain new importance to me each time I encounter them. At times, when I feel pressure to constantly be moving, producing content, or responding to the constant influx of information, I just recall Lorraine Hansberry’s words from A Raisin in the Sun (1959): “Don’t get up. Just sit a while and think. Never be afraid to sit a while and think.”

This year, I read many books for the first time and continued a ritual of rereading of a few of my favorite works. Of those that were new to me, the republication of Anarchism and the Black Revolution by Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin (Pluto Press, 2021), A Little Devil in America by Hanif Abdurraqib (Random House, 2021), Shadowboxing by Joy James (1999), The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), and My Body by Emily Ratajkowski (Metropolitan Books, 2021) still weigh on my mind. The works I continue to revisit, Negroland by Margo Jefferson (Vintage, 2016), Passing by Nella Larsen (1929), A Small Place by Jamaica Kincaid (1988), White Negroes by Lauren Michele Jackson (Beacon Press, 2020), Fantasia for the Man in Blue by Tommye Blount (Four Way Books, 2020), and Scenes of Subjection by Saidiya Hartman (1997) gain new importance to me each time I encounter them. At times, when I feel pressure to constantly be moving, producing content, or responding to the constant influx of information, I just recall Lorraine Hansberry’s words from A Raisin in the Sun (1959): “Don’t get up. Just sit a while and think. Never be afraid to sit a while and think.”

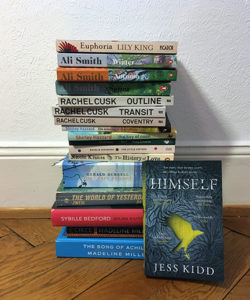

Ophelia John, Digital Copyeditor

After reading Lily King’s fabulous Writers & Lovers (Grove Atlantic, 2020), I devoured all of her earlier work this year. My favorite, Euphoria (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2014), tells the story of a love triangle of three anthropologists working in New Guinea. Loosely based on the experiences of Margaret Mead, Reo Fortune, and Gregory Bateson, Euphoria broadens and breaks the heart—just like Ali Smith’s novels of the seasons. Autumn (Anchor, 2017) depicts a tenderly unusual relationship between two people of vastly different generations, while Spring (2020), which is also a political novel, includes a deep affinity that lasts a lifetime. Smith is wildly talented; the formal comparisons made between her and Virginia Woolf aren’t exaggerated. I’m still reading Winter (2018) and have yet to pick up Summer (2021). Another pile on my table consists of Rachel Cusk’s Outline Trilogy (Picador, 2016–2018) and her brilliant essay collection Coventry (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019). If you’re interested in what it means to be female, these books are for you. Cusk’s mesh of form and content, especially in Outline, is amazing, and I’m going to go reread it as soon as I finish writing this. The most surprising book I read this year is one I dearly wish I’d written: Jess Kidd’s Himself (Washington Square Press, 2017) is a highly literary magical-realist murder mystery set in back-of-beyond Ireland. Centered on death, every page of Kidd’s novel brims with love, hatred, desire, wit, sadness, hope, and wonder—in a word, life.

After reading Lily King’s fabulous Writers & Lovers (Grove Atlantic, 2020), I devoured all of her earlier work this year. My favorite, Euphoria (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2014), tells the story of a love triangle of three anthropologists working in New Guinea. Loosely based on the experiences of Margaret Mead, Reo Fortune, and Gregory Bateson, Euphoria broadens and breaks the heart—just like Ali Smith’s novels of the seasons. Autumn (Anchor, 2017) depicts a tenderly unusual relationship between two people of vastly different generations, while Spring (2020), which is also a political novel, includes a deep affinity that lasts a lifetime. Smith is wildly talented; the formal comparisons made between her and Virginia Woolf aren’t exaggerated. I’m still reading Winter (2018) and have yet to pick up Summer (2021). Another pile on my table consists of Rachel Cusk’s Outline Trilogy (Picador, 2016–2018) and her brilliant essay collection Coventry (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019). If you’re interested in what it means to be female, these books are for you. Cusk’s mesh of form and content, especially in Outline, is amazing, and I’m going to go reread it as soon as I finish writing this. The most surprising book I read this year is one I dearly wish I’d written: Jess Kidd’s Himself (Washington Square Press, 2017) is a highly literary magical-realist murder mystery set in back-of-beyond Ireland. Centered on death, every page of Kidd’s novel brims with love, hatred, desire, wit, sadness, hope, and wonder—in a word, life.

Yasmin Tayeby, Newsletter Editor

This past year being what it was, I was looking for some comfort reading. Shelf Life: Chronicles of a Cairo Bookseller by Nadia Wassef (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021) turned out to be just that. After almost three years of being unable to visit my home country of Egypt, Wassef’s book was as close as I could get. Shelf Life is a love letter to Diwan, the bookstore Wassef opened more than two decades ago. I went to school down the street from the flagship store, and my childhood apartment is a few blocks from their third. Wassef’s descriptions of her staff and clientele are spot-on. One of my favorite excerpts is a passage that somebody who hasn’t spent much time in Egypt would probably glance over without a second thought: “Each shop seemed to have one man at the front desk, sipping tea and sleep-reading a newspaper. I’d request a title, and the man would slip his bare foot partially back into his sandal, leaving his cracked heel to press upon the floor.” I can’t tell you how many times I have seen this cracked heel partially slipped into a “shib-shib,” as it’s called in Egypt. Wassef’s honesty, when it comes to the love she bears for Diwan and its often detrimental effect on her family, is refreshing. She manages to weave seamlessly in and out of autobiography and sociopolitical commentary, making this more than just a businesswoman’s memoir.

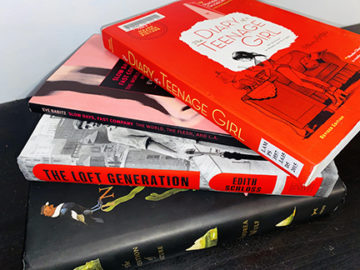

Gabby McClellan, Intern

Lately, I’ve been reading The Diary of a Teenage Girl by Phoebe Gloeckner (Frog Books, 2002), an interesting mix of novelistic prose, comic strips, and graphics. As someone who has very little experience with graphic novels, I was excited to give this one a try. So far, I am impressed by how Gloeckner tackles adolescence, sexuality, and the expectations of youth all through the witty, sarcastic voice of her fifteen-year-old narrator, Minnie. I grew to know Minnie so well that by the first sequence of comics I could already predict the thoughts behind her facial expressions. I also I recently finished Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (Penguin Press, 2018) and absolutely loved it. The dialogue was smart, funny, and biting, and the novel became both a searing indictment against materialistic culture and a dark and painful spiral. On my “To Read” list, I have the Jennifer Croft’s English translation of Olga Tokarczuk’s new novel, The Books of Jacob, which will be released in February (Riverhead Books). I’ve been a huge Tokarczuk fan for many years; my copy of Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead is well-worn, having been passed around among neighbors and friends. I’m also eager to reread Andrea Wulf’s The Invention of Nature (Vintage, 2016), an account of Alexander von Humboldt’s life that reads like an adventure story.

Lately, I’ve been reading The Diary of a Teenage Girl by Phoebe Gloeckner (Frog Books, 2002), an interesting mix of novelistic prose, comic strips, and graphics. As someone who has very little experience with graphic novels, I was excited to give this one a try. So far, I am impressed by how Gloeckner tackles adolescence, sexuality, and the expectations of youth all through the witty, sarcastic voice of her fifteen-year-old narrator, Minnie. I grew to know Minnie so well that by the first sequence of comics I could already predict the thoughts behind her facial expressions. I also I recently finished Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (Penguin Press, 2018) and absolutely loved it. The dialogue was smart, funny, and biting, and the novel became both a searing indictment against materialistic culture and a dark and painful spiral. On my “To Read” list, I have the Jennifer Croft’s English translation of Olga Tokarczuk’s new novel, The Books of Jacob, which will be released in February (Riverhead Books). I’ve been a huge Tokarczuk fan for many years; my copy of Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead is well-worn, having been passed around among neighbors and friends. I’m also eager to reread Andrea Wulf’s The Invention of Nature (Vintage, 2016), an account of Alexander von Humboldt’s life that reads like an adventure story.

Alex Ankai, Intern

During the pandemic there were times when I wouldn’t leave my home for days. On top of the utter lack of structure, sunlight, and movement, I found that everything from my energy level to my desire to learn seriously dwindled. That’s when books re-entered my life! I discovered that I love audiobooks, listening to them in the morning and reading on my Kindle at night. Some of my favorite things to read were works that took me out of the monotony of quarantine. I particularly enjoyed Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir In the Dream House (Graywolf Press, 2019), Stephen King’s apocalypse novel The Stand (1978)—the audiobook was around fifty hours long—and Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813). I also read a lot of YA and YA fantasy series, including Wink Poppy Midnight by April Genevieve Tucholke (Dial Books, 2016), the Twilight Saga by Stephenie Meyer (Little, Brown and Company, 2005–2008), A Discovery of Witches by Deborah Harkness (Penguin, 2011), and A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas (Bloomsbury, 2015).

During the pandemic there were times when I wouldn’t leave my home for days. On top of the utter lack of structure, sunlight, and movement, I found that everything from my energy level to my desire to learn seriously dwindled. That’s when books re-entered my life! I discovered that I love audiobooks, listening to them in the morning and reading on my Kindle at night. Some of my favorite things to read were works that took me out of the monotony of quarantine. I particularly enjoyed Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir In the Dream House (Graywolf Press, 2019), Stephen King’s apocalypse novel The Stand (1978)—the audiobook was around fifty hours long—and Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813). I also read a lot of YA and YA fantasy series, including Wink Poppy Midnight by April Genevieve Tucholke (Dial Books, 2016), the Twilight Saga by Stephenie Meyer (Little, Brown and Company, 2005–2008), A Discovery of Witches by Deborah Harkness (Penguin, 2011), and A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas (Bloomsbury, 2015).

We hope that if you pick up any of these reads for yourself or a friend, you’ll support your local independent bookstore.

Published on February 7, 2022