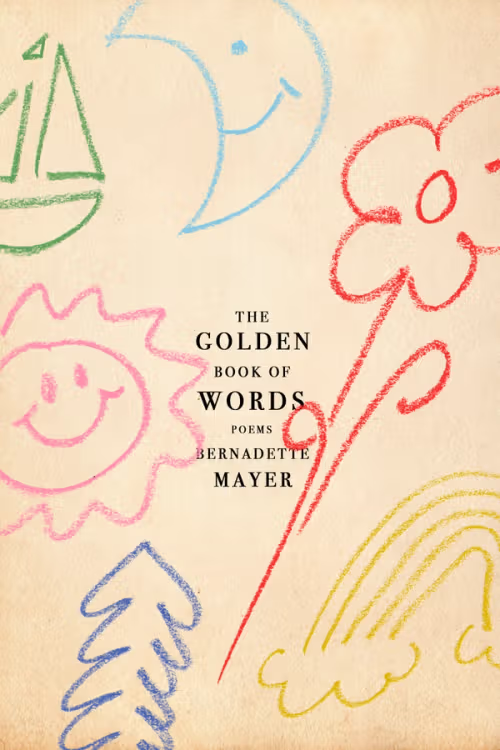

The Golden Book of Words

Bernadette Mayer

reviewed by Jeffrey Careyva

Nobody makes the everyday more interesting than Bernadette Mayer. In The Golden Book of Words (1978), Mayer takes a step away from the intensely conceptual and procedural poetics that made her a second-gen New York School mainstay as she developed a more lyrical but no less cerebral style. This early book, just republished by New Directions, shows Mayer devoting herself to writing down her daily conscious experiences, from childcare and snow shoveling to lingering dreams and passing anxieties. She writes steadily, with the loquaciousness and good humor that come after a few beers and the craft that comes after reading aloud Little Golden children’s books by day and Milton’s Paradise Lost by night.

A poem like “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” showcases Mayer’s perceptive descriptions of motherhood while outlining the cycles and circadian rhythms that envelop all our lives:

Moon out and no snow yet, November first

The first anniversary of our wedding and

The day before election day, 1976, yesterday

Was Halloween, next Friday I have an appointment

…

The time between dinner and Marie’s bedtime is too long

When it’s time to go to bed there’s still a few hours left

To read, I’m dreaming twice as much as before

I spend all my new time lying in bed thinking.

Last night I saw “Invasion of the Body Snatchers”

And tonight when I came into my room to go to work

I found an old seed pod on the floor by my desk.

In the movie if you see one of these it’s time to die.

Writing about her day often shifts from physical to emotional territory, and “The Invasion of the Body Snatchers” is one of many funny poems that describe Mayer and her then-partner Lewis Warsh’s move from NYC to Lenox, Massachusetts, where Mayer sometimes felt like a trespasser in the physically and emotionally cold New England environment.

The impulse for storytelling runs across The Golden Book of Words, and Mayer offers reports of snowed-in winters, run-ins with Lenox’s familiar loons, flowers coming up in the garden, good sales at the health-food store, and how it’s too late for her to become a real farmer. Her poetry will not melt the snow or thaw the feelings of her neighbors, but the poems offer an alphabetic variety from ekphrases of beer bottles to imitations of Early Modern English versification.

As Mayer writes in “Lookin Like Areas of Kansas,” “New England is awful / The winter is five months long / The sun may come out today but that doesn’t mean anything / There are Yankees,” but The Golden Book represents a period of intense productivity in Mayer’s career, when she balanced domestic care work with a daily writing schedule made possible by isolation in a small town. For Mayer, being a writer is a serious profession, as serious as being a teacher or a farmer or a snowplow driver—even though it pays much less. As she writes in “Essay,” Mayer finds herself “Steadfast as any farmer and fixed as the stars” while poets like her work as “Tenants of a vision we rent out endlessly.”

Mayer’s downtown Manhattan peers did not wholly get or appreciate Mayer’s newly prominent lyrical and motherly impulses, and it’s hard to read a poem like “I Imagine Things” but as an ars poetica of Mayer’s aesthetic anxiety:

I feel I’m not a good poet, I’m half a poet, I lose my poethood, I don’t compose knowing enough, I don’t go far enough away, I’m too close to myself, I don’t lose myself enough, I must free the language more, I free it too much, and now it’s lost, lost to you and others too … wait, now I see what others are doing, they’re imposing a discipline and saying now I can’t speak of myself anymore, I must describe the wall of bricks and the little limited visa I’ve here, I must describe that man and his dreary coat … This dense, blocky prose poem harnesses Mayer’s knack for exhaustive, stream-of-consciousness composition to push back at those who would mock her descriptions of domestic, inner, and oneiric life. There were rumored feelings of betrayal among the emerging “Language” writers when Mayer began to capitalize the first letter of each line, refer to her readings of classics like Hawthorne and Proust, and offer candid depictions of how she was feeling in many poems.

Mayer throws in the occasional rhythming couplet or quatrain, a nod to the style of children’s books as much as to the inventive writing she would later pioneer in Sonnets (1989), or to the lyrical inventory of daily life she soon mastered with the much-acclaimed Midwinter Day (1982). In the meantime, “Eve of Easter” demonstrates Mayer already reckoning with her milieu’s (mostly male) literary inheritance, the thanklessness of domestic labor, and the myopia that could come from writing only about oneself:

Milton, who made his illiterate daughters

Read to him in five languages

Till they heard the news he would marry again

And said they would rather he was dead

Milton who turns even Paradise Lost

Into an autobiography, I have three

Babies tonight, all three are sleeping:

Rachel the great great great grandaughter

Of Herman Melville is asleep on the bed

Sophia and Marie are sleeping

Sophia the namesake of the wives

of Lewis Freedson the scholar and Nathaniel Hawthorne

Marie my mother’s oldest name, these three girls

Resting in the dark, I made the lucent dark

I stole images from Multon to cure opacous gloom

Mayer trawls a complicated line of descent from literary forefathers to the women left to take care of them, to the women often left out of the stories about anxiety of influence. High and low, old-fashioned and newfangled, and the dense detail of descriptive prose with the emotional concentration of lyric poetry—all come together in Mayer’s golden early collection.

Published on August 14, 2025