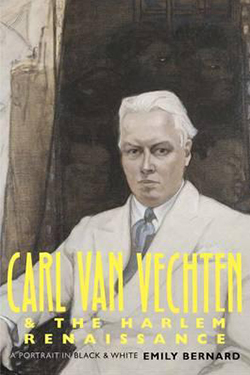

Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance: A Portrait in Black and White

by Emily Bernard

reviewed by Cameron McWhirter

Carl Van Vechten is best-known today not for who he knew or what he wrote but for the title of his most famous novel: Nigger Heaven. For a white man to use that phrase—derogatory slang for the upper galleries of theaters where black people were once segregated—as the title of a novel about Harlem horrified many people, even in 1926.

Early in his novel about young lovers, set amid artists’ dinner parties and cabarets, a woman named Ruby tells her man: “Dis place, where Ah met you—Harlem. Ah calls et, specherly tonight, Ah calls et Nigger Heaven!” Modern readers wince at the dialect as well as the title, and the novel, though a bestseller when it was published, has had few reprints since. The reputation of Van Vechten, the lanky, white, Iowa-born writer who devoted much of his life to promoting and chronicling the black artistic and literary scene, has also suffered. Where do scholars put this odd man in their studies of the African American literary phenomenon known as the Harlem Renaissance?

That question has long vexed Emily Bernard, associate professor of English and ethnic studies at the University of Vermont, whose book explores Van Vechten’s strained but ultimately vital relationships with a wide range of Harlem artists. This concise, well-wrought study is not a biography though it is replete with biographical detail. Rather, it is an exploration of one white man’s obsession with blackness and how, as Bernard writes, it became “a central theme in the story of his life.”

Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance is in part a delayed companion to Bernard’s excellent edition of letters, Remember Me to Harlem: The Correspondence of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten, published in 2001. Bernard, who is African American, became fascinated with Van Vechten early in her studies of the Harlem Renaissance and has spent years trying to figure out his place in the constellation of Harlem literati. The picture that emerges is complex and, at times, ugly. Bernard illuminates Van Vechten’s pivotal if troublesome role in the Harlem scene, but it also raises broad questions, such as what is authentic black art, as opposed to art shaped by white expectations of what black art should be? Many scholars have simply avoided Van Vechten over the years, downplaying his role in the Harlem Renaissance. Bernard understands his awkward, unavoidable importance.

In the 1920s, Van Vechten was the self-appointed ambassador for New York’s black art, music and literary scene and the main interpreter of Harlem to white America. Through his connections with white publishing houses and wealthy patrons, he secured deals for black writers and artists. This helped many black artists, but also gave Van Vechten inordinate control of who got white largesse; appeasing his tastes (and ego) often became crucial to success.

Today it is easy to dismiss him as a man with a “Negro fetish,” but Van Vechten was a conflicted composite of artistic insight, sincerity, and progressive impulses, as well as pettiness, vanity, and racist views. He simplistically saw the strength of black literature, music and art as a core primitivism, an earthy counterpoint to what he considered tepid white culture. His view of black culture was largely anthropological, as a tourist among the exotics, and much of his work on behalf of black artists today seems paternalistic and condescending. He loved to take groups of famous whites—including at one point H. L. Mencken and at another a drunk William Faulkner—on tours of Harlem’s black and tan cabarets, showing off what Emily Bernard sarcastically labels “the Congo of upper Manhattan.”

And then there was the problem of Nigger Heaven. Van Vechten was very aware that the title of his novel about black life would offend when he published the book in 1926. Before publication, his father begged him to change it, and close black friends like James Weldon Johnson counseled him not to use the title. Johnson’s wife Grace told Van Vechten that both the title and the book would be hated. But he ignored their advice. He wanted to shock for publicity’s sake, and a part of him thought he had earned some honorific position in black society that gave him protected status.

Early in Nigger Heaven, a character says the word and Van Vechten adds this footnote, the only one in the book: “While this informal epithet is freely used by Negroes among themselves, not only as a term of opprobrium, but also actually as a term of endearment, its employment by a white person is always fiercely resented.” Somehow he thought this rule would not apply to him, since many black artists, including Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, considered him a close ally and friend. He was wrong.

W. E. B. Du Bois despised the title and the book, calling it “a blow in the face.” Others, like Alain Locke, agreed. At one point, a black crowd burned it. Dislike of Van Vechten among many black intellectuals continues to this day; historian David Levering Lewis has described Nigger Heaven as “a colossal fraud.”

But to view Van Vechten solely as a racial dilettante is to misunderstand the man, the racial boundaries he crossed, and the artistic world in which he operated. As the singer Ethel Waters once said, Van Vechten was “credited with knowing at the time more about Harlem than any other white man except the captain of the Harlem Police Station.”

Bernard has done a wonderful job of bringing Van Vechten to life and showing his inconvenient place in the Harlem movement. She presents his many flaws, his confused views, and his failings. But she also presents his genuine efforts to help black artists, his kindness, and his importance to Harlem in the 1920s. A tireless promoter and chronicler of the black art scene, he was, in her words, “a Negrophile bar none.”

Published on June 10, 2013