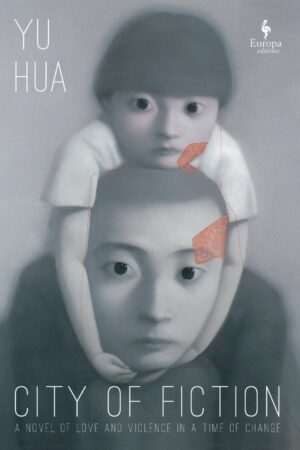

City of Fiction

by Yu Hua

reviewed by Victoria Zhuang

Lin Xiangfu has roamed over a thousand li across provincial China and its towns, in search of his vanished bride Xiaomei. In a coarse bundle upon his back he carries their infant daughter. However, the town he is searching for doesn’t exist.

Such is the epic premise of Yu Hua’s latest novel City of Fiction, which explores the hold that places have upon us, even when they live only in our minds.

We are in the twilight of China’s imperial age, and the Qin dynasty is in its death throes; soon bandits will ravage the countryside. Shortly after their wedding, Xiaomei steals from Lin Xiangfu, making off with nearly half his family’s savings in gold. After returning to deliver their child, and despite promising to stay, she once again disappears from his village in the north. Xiaomei had said that her hometown in the south was called Wencheng, but nobody has heard of such a place. The name in Mandarin literally means “fictional” or “literary” city. Instead, Lin Xiangfu suspects that another southern town called Xizhen may be the real Wencheng. He builds a life for himself and his daughter there, becoming a successful carpenter and furniture maker. As the years pass, he remains on the lookout for Xiaomei, but terrifying forces arrive and threaten to destroy his new homeland.

Yu Hua paints a lush portrait of rural China in this tumultuous period of change, which is adroitly captured in Todd Foley’s English translation. We wander among dusty country roads, moss-covered green hills, and muddy swamps, and we witness lives lost and regained on the banks of an immense river bordering Xizhen. On the streets, as the residents chatter in Xiaomei’s rapid cadence, the women wear blue calico headscarves, and their clogs echo on the pavement, as Xiaomei’s shoes did, with a sound like xylophones. Here, young lovers pine for each other, parents arrange marriages, craftsmen peddle fine wares, and teachers give instruction in the Confucian classics.

These pastoral small-town moments are punctuated by ones of strident human cruelty. As criminal gangs seize hostages and later lay siege to Xizhen, scenes of battle, rape, torture, pillaging, and mass murder abound. The third-person narrator coldly relates each moment of suffering in a world where the stability of life in old China is gone. The bandits gleefully cut off body parts, rape their victims with bamboo sticks, burn them with coals, and beat and starve them, in passages that are as brutal as others are tender—ones where close friends tearfully part ways and parents delight in feeding their baby a snack of haw berries.

The novel abounds with loose threads and denies closure on many fronts. Certain characters who appear central to the plot—a gentle prostitute, a rich man’s nasty son who is betrothed to Lin Xiangfu’s daughter, and the daughter herself, who grows to become a beautiful young woman—are suddenly ushered offstage and never heard from again.

Yu Hua does unravel the mystery of Xiaomei’s past in a second, shorter part of the book, which is told mostly from her perspective. Xiaomei was born into an impoverished peasant family, brought up without love, and expected to submit to her future husband. Raised in the old China, she had her feet bound as a child, but as an adult she glimpses the coming independence of modern Chinese women. Xiaomei journeys northward, searching for a better life in an imperial Beijing that she will never reach. Instead, she encounters and falls in love with Lin Xiangfu. However, Xiaomei guards a sad secret which compels her to leave him.

It is gratifying to pull back the curtain on certain earlier scenes in the novel, along with certain details that take on new significance, by revisiting them from Xiaomei’s point of view. However, Xiaomei’s tale feels comparatively rushed, and the novel ends on a general note of uncertainty, even as it brings certain plot points full circle.

That sense of an open wound, of connections denied and lives lost to the grind of history, is perhaps the point. In one moment, Lin Xiangfu comes achingly close to reunion with his beloved Xiaomei. But even then they are prevented from communicating with each other. “They were right beside each other—so close, separated only by a tiny distance.”

City of Fiction transports us to the China that was coming into being at the dawn of the twentieth century and evokes the lost world of the Chinas before it. Yu Hua documents the beauty and violence in that collective past, which continue to haunt the Chinese people; he teases the possibility of recovering forgotten ways of life while acknowledging that the future is still unwritten.

Like the stoic peasant farmer Fugui in his signature novel To Live, Yu Hua’s characters simply endure. When Lin Xiangfu first arrives in Xizhen, a tornado rips through the community and razes many homes. “Crops in the fields were flattened as if they were nothing more than trampled weeds,” Yu Hua writes. “Despite this scene of destruction, Lin Xiangfu was still able to see the fertile richness of the Wangmudang, as if recognizing the former beauty in the face of an old woman.” With Lin Xiangfu’s help, Xizhen’s residents rebuild after the storm. The past they seek to recreate may be gone, but the vision of what it was and could be impels them to start over, in the face of countless natural and human-made calamities. Such is the power of the imagined to engender what is.

Published on September 16, 2025