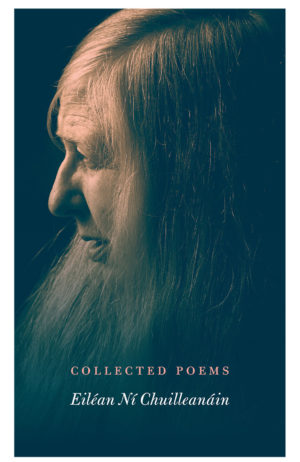

Collected Poems

by Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin

reviewed by Carmen Bugan

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s poetry works like memory, situating itself between what is real and what insists on being named as real, reaching a sharpened significance with each successive return. Questioning the certainty of our perceptions, her poems meditate on the nature of truth and reality; questioning whether we are what we think we are, they are also philosophical explorations of identity. Her Collected Poems reads like the library she describes in “Two Poems for Pearse Hutchinson”: “a case of blades, / every one sharpened and the sharpest closest to hand.” Born in 1942 in Cork, Ní Chuilleanáin was Ireland’s Professor of Poetry from 2016 to 2019 and enjoys the status of one of her country’s foremost poets.

The Collected Poems comprises nine collections of poetry, beginning with Acts and Monuments (1972) and ending with a coda that follows Ní Chuilleanáin’s 2020 New Poems. These collections have consistently enjoyed international praise: The Boys of Bluehill (2015) was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection; The Sun-fish (2010) won the International Griffin Poetry Prize; The Magdalene Sermon (1989) was selected as one of the three best poetry volumes of the year by the Irish Times/Aer Lingus Poetry Book Prize Committee.

Exploring both nationality and cosmopolitanism, Ní Chuilleanáin’s perspective is guided by her work as a translator (her translations of Romanian women poets are some of the finest to date), and her deep knowledge of several European literary traditions. Womanhood is a constant preoccupation in her poetry; the figure of the woman is viewed through the lens of history, religion, landscape, and mythology.

Women are ever-present in the house, a setting visited throughout the collection. Houses—left behind, subject to the transformations of time—are rich images for Ní Chuilleanáin. Take, for example, “The Tree”:

The house we left in nineteen forty-nine—

and who knows now how many children

have grown up in that same place since then—

the tree is alive that my father planted there.[ … ]

That’s where I learned how the world is

between men and women, my mother with us at home,

my father coming home, her asking him in Irish

“Have you any news?”

“The Tree” enters into conversation with Ní Chuilleanáin’s earlier poem “The House Remembered,” where outside and the inside are inverted, the house’s scaffolding enduring while the stone that makes the structure crumbles: “The house persists, the permanent / scaffolding while the stones move round. / Convolvulus winds the banisters, sucks them down.” Yet, no matter the house’s transformations, “coming through the door all fathers look the same.” Like the house, the poems are filled with intuitions and intimations of pain, fractures that can be seen through.

In “The Percussion Version,” the multiplicity of perception is revealed through sound. Inside the house, there is music, the reason “why we gather / to listen to the scrabbling and the sound test, / the way the splash cymbal explores the limits.” But,

From the outside how different: I paused

beside the door and all I could hear

was a chair scraping into silence

and presently a soft step climbing,a sigh from the upper floor, at which

in the room below something knocked just once

and the well in the back yard answered

with a bass vibrating groan.

While inside the house “the bell note / rings and rises like a cloud in the ceiling,” stirring the imagination, from the outside everything seems plain and domestic, comforting but devoid of possibilities. It’s a portrait of life: we seem readable to one another, yet within ourselves there are inscrutable melodies. Inside and outside are destabilized and the border between the plain and the mysterious becomes porous.

How is one to live with constantly competing perceptions, fractures, and doubts? Our method of communication, language, can clash with itself—and thus bring an awareness of how fragile our houses are, how fragile and misunderstood our lives are. This is powerfully articulated in “The Words Collide,” in which Ní Chuilleanáin presents a scene of competition between personal language and a larger, collective language. In this poem, a scribe is asked to tell the story of a woman who “wants to tell her dream to the only one / who will get the drift.” “The scribe objects,” saying, “you can’t put it like that.” The scribe’s obstinate refusal to write out the woman’s thoughts causes her to doubt herself: “she saw she had got it wrong.” The poem ends devastatingly with the scribe’s excuse for why many will never be heard—he seems to say that a woman’s silence will protect a fragile larger world:

[ … ] He said,

You can’t put those words into your letter.

It will weigh too heavy, it will cost too much,

it will break the strap of the postman’s bag,

it will crack his collarbone. The bridges

are all so bad now, with that weight to shift

he’s bound to stumble. He’ll never make it alive.

Despite its portrayal of a fractured and often painful reality, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s Collected Poems offers integral thinking and deep feeling about the consolatory power of words. For all its complications, the inevitable collision of words makes it possible to “Leave behind the places that you knew” and believe that “all that you leave behind you will find once more.”

Published on August 27, 2021