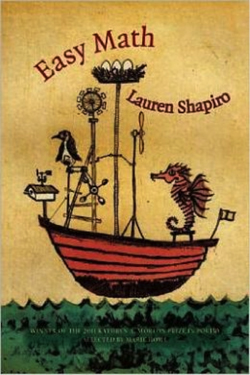

Easy Math

by Lauren Shapiro

reviewed by Henry Hughes

Easy Math offers thoughtful problems on every page, but very few will ever be solved. Lauren Shapiro’s collection rides the newest wave of elegant confusion springing from the old New York School of modern verse, where verbal confusion purposely defies conventional reading. Along with 1950s- and 60s-era innovations in the visual arts and music, these non-representational forms showed us that words, paint, and notes needn’t tell a clever story, color a bowl of fruit, or phrase a catchy tune. But what do they do?

Lauren Shapiro seems aware of this legacy in one of her more narrative poems, “What to Do,” which alludes obliquely to Dickinson’s “I Died for Beauty” and Ashbery’s famous 1975 poem “Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror.”

I begin by painting the nude woman.

She is a cantaloupe in the most famous

still life in history. The world is reflected

in the belly of the nude that shows me only

an ever-repeating image of myself.* * *

I hear her whispering. Are you speaking

of beauty? I ask. She wants lunch.

We eat the still life next to her.

I can’t even get into what happens next.

When I have finished the painting

it hangs in the student show.

A man looks at it. He doesn’t know what to say.

It’s colorful, he says.

Thanks, I say.

After nearly a half-century of this kind of poetry, what more can we say? It’s colorful!

Like the work of her mentors, James Tate and Dean Young, Shapiro’s poetry is meant to be experienced rather than understood. Speaking to the editors of Jubilat, Dean Young remarked that “to tie meaning too closely to understanding misses the point.” Shapiro’s writing is often untied, yet vivid in its sharp descriptions and loopy wit. There’s a crazy pleasure in following these wild associations where humor remains one of the more tangible rewards. In “Nothing Is More Beautiful When You Try to Make It that Way, Joan Rivers,” we learn that aging celebrities are negotiating to sell a sex tape of “their famous bodies / grinding into each other like hard candy.” Then we hear “you’re not supposed to eat / rock candy, just look through it to see / how pink and crystalized the world becomes.”

Shapiro’s craft succeeds best when the connections between the felicitous items of her free-wheeling imagination are more carefully planned. Some poems come together only as pop culture pastiches, glib lists, or Twittery gossip. But in “Canis Soupus” she collars the scientific neologism for the genetic mess of wild and domestic canine interbreeding and loosely leashes it to a girlhood doll “with black curls and a lazy eye,” a shifting rock that causes a mining disaster, the business adage “to sell yourself,” and “pixelated hamburgers,” returning doggedly to “wet or dry food, mutts or pure breeds”—a recombination of fragments that admits “an infinite number of ways to torture the soul with hopefulness.” This works.

“Dominoes” demonstrates even better the great possibilities for this kind of poetry, approaching a symbolist style of metaphor-building in which absurd juxtapositions feel perceptive rather than gratuitous.

Life is mirrors pointed at other mirrors and then one day

your mom comes in and breaks them all.

She says her mother made her do it.

And her mother’s mother put rocks in the soup

and tied toys too high to reach.

Nobody knew that woman’s mother

but legend has it she wasn’t a woman at all

but a giant prehistoric mermaid. She did her best,

but her kind was never meant to survive the treacheries

of evolution. Oh, lighten up. So your parents got divorced,

and when they fought you went outside to play

but all your toys were hanging in a net at the top of a tree,

including the transformer truck you got for your birthday,

and there was a bird making a nest in it.

Why couldn’t you see any beauty in that?

Family connections and the generational histories and cultural fables that explain them are beautifully smashed in the collapsing panels of “Dominoes.” And unlike most of the poems in this book, the game of words ends in a moment of felt human emotion when the child, or perhaps the grown victim of chaos and deprivation, is asked to look on the bright side, to behold the beautiful transformation. This could be a cruel thing to say to someone, like the lawyer telling Bartleby the ex-scrivener to enjoy the sky and grass of the prison grounds, or it could be a ticket to enlightenment. “Lighten up,” Shapiro is telling us—see the beauty hatching in the chaos of these poems.

Poems need not be mere riddles or math problems. Whether it’s Dogen or Dickinson, some of the world’s most meaningful poetry remains open, cryptic and unresolved while still inviting us to respond as humans. “A poem should not mean / But be,” Archibald MacLeish told us way back in 1926. But how much being can a reader endure? In a very favorable New York Times review of Adam Fitzgerald’s The Late Parade—a poetry collection in the vein of Easy Math—David Kirby wrestles with similar issues, concluding: “Absurd on the surface, Fitzgerald’s mash-ups make a kind of sense that is brainy . . . and explosively funny.” But Kirby also expresses fatigue with the “overhoneyed lushness” of the style, wishing the poet would “back off occasionally and let the reader relax with a few poems that are starker and less dense.” Shapiro’s lines are less formally bricked than Fitzgerald’s and they breathe easier. Nevertheless, both poets avoid sincere human conversation as a way toward insight. It’s often said that New York School poetry is the verbal equivalent of abstract expressionism in painting. But visual design elements in our cities, buildings, kitchens (even that paint splattered drop cloth in the garage) prepare us for modern art in a way that this play of verbal language, which meets so few expectations of human communication, does not. Lauren Shapiro’s first book is wonderful at “sending off beautiful little equations into the air.” Her next book might demonstrate a few proofs.

Published on July 3, 2014