How to Be Drawn

by Terrance Hayes

reviewed by Kevin T. O'Connor

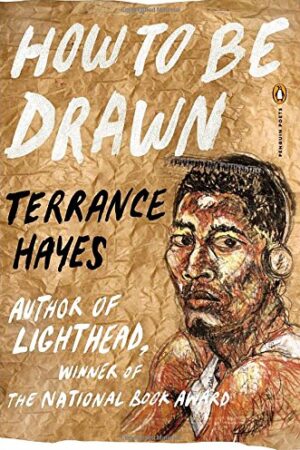

The title of Terrance Hayes’s fifth book of poems, How to Be Drawn, works as an elastic motif within a dazzling collection that often revels in how sound and word play (puns, homonyms, deconstructed idioms) can lead to meaningful discoveries. The author, who also studied as a painter, draws his self-portrait on the cover as well as in the lyrics of a book that—like Whitman’s omnivorous, self-cloning Song of Myself—expands to contain a multitude of voices and subjects and tonal registers. Poetry, defined simply as memorable speech, comes in many forms; and while there is plenty of musical and formal pleasure in Hayes’s work, one should not expect a refined euphony or a self-enclosed aesthetic. This poetry tends to employ a grittier demotic. Its dynamic is centrifugal and—in the African-American tradition of Gwendolyn Brooks, Amiri Baraka and Etheridge Knight—urgently engaged.

Hayes’s poems take on subjects of racial identity, social injustice, violence, family dysfunction, and everyday personal loss—but they never succumb to the pain and desolations they treat. This is a buoyant, often funny, book, full of bluesy wisdom and pathos limned with bruising laughter. The poems push against the limits of genre and form, working sometimes like soul songs, other times like verbal action-paintings, and other times like Pound’s notion of logopoeia, a ”dance of the intellect among words.” It is wonderful to hear the poet assume different speaking roles and voices: he can sound not only like a jazzy master-of-ceremonies, but at times also like a renegade preacher, a séance leader, an exorcist, a cabaret show impresario, or just the irreverent know-it-all down the street performing for friends and neighbors.

On one level, How to be Drawn is the ultimate in ironized self-help books and instruction manuals: “How to be Drawn to Trouble” features a James Brown lyric and prison anecdote to explore the fierce, pent-up tensions of marital and familial passion; “How to Draw an Invisible Man” lovingly critiques the legacy of an exhumed Ralph Ellison, while “We Should Make a Documentary About Spades” is just one of several gaming strategies to survive the traumatic legacy of slavery and racism; “Antebellum House Party” and “Confederate Ghost Story” extend this instructor’s reach to include historical “reconstruction” and the caustic invocation of avenging spirits; and the book’s penultimate poem, “How to Draw a Perfect Circle,” imagines art as a ritual of restorative embodiment for a black man killed after gouging out a policeman’s eye:

When the part of the body that holds the soul is finally decomposedIt becomes a circle, a hole that hold everything: blemish, cell,

Womb, parts of the body no one can see …

The poems in How to Be Drawn often radiate from a central concept or image toward even more radically inventive forms. “Portrait of Etheridge Knight in the Style of a Crime Report,” written in boxed categories and containing facts about a subject’s arrest for drugs, works as a kind of poignant de-sublimated anti-poem—where a great soul is reduced and confined by procedural forms. Hayes’s exuberant, even manic humor seems inspired by incongruous sources: “Who Are The Tribes?” uses the premise of an Einstein logic puzzle to categorize the habits and idioms of street gangs, and “Gentle Measures,” whose section titles are taken from a genteel nineteenth-century primer on child rearing, becomes an exercise in sustained irony as the speaker announces in the first section,

First, I would like to have with 196 women from the world’s

196 nations 196 children, then I would like to abandon them.

More often, Hayes’s poems are inspired by other art forms. He continues to draw from eclectic genres of popular music—blues, soul, rap—and even a plaintive ballad by Leonard Cohen. But How to Be Drawn marks a special focus on visual arts, particularly avant-garde conceptual art like that of the late graffiti/performance artist Rammellzee, whose subversive idea of “letter racers” serves as the book’s epigraph, or of Jenny Holzer, whose aphoristic LED-flashing “truism”—“Protect Me From What I Want”— inspires the poem “A Concept of Survival.” “Wigphrastic,” based on a series of Ellen Gallagher’s images reproduced from popular sources, is Hayes’s irreverent take on the usually high-toned tradition of the ekphrastic, a wigged-out catalogue of sound-fueled identities and wordplay:

Isis wigs, Cleopatra wigs, Big Booty Judy wigs

Under the soft radar-streaked music of Klymaxx

Singing, “the men all-pause when I walked into the room.”The men all paws. Animals, The men all fangles,

The men all wolf-woofs and a little bit lost, lust,

Lustrous, trustless, restless as the rest of us.

That Hayes offers his readers references for his poems on a multimedia website says much about his aesthetic and cultural stand. While Eliot’s infamous notes to The Wasteland made his own poem seem esoteric, if not derivative, Hayes’s post-electronic age touchstones are first-hand, mutually interactive phenomena which clarify his ambition in individual poems and simultaneously pay homage to the originals.

But Hayes is a restless artist and a bit of a shape-shifter. His final dedicatory, “Ars Poetic for the One Like Us”—in my mind, the best single poem in the volume—is also its quietest, most deeply reflective, and most aesthetically finished. In it he re-imagines the deepest sources of the poetic impulse:

I like the story about the man who talks

God into letting him live until he is done

With his masterwork. In some versionsHe is a painter, but in this one he is a singer

Who then sings every sentence, whose song

Becomes a poem that does not endBecause it is eternally revised. Who can say

Whether Orpheus, when he found honey

In other hives, did not sing to let the devil knowHis body was alive? He was the first to grieve,

Years in advance, the news of his death.

In the poignant final lines the reader hears the poet at once reminding himself of the inherent limits of any verbal art— and imagining the next ambition in his own:

Some things in this world

Do not depend on speech to be felt.

Remember too that the eyes are not flesh,

That crisis is initiated by the absence of witness,That Orpheus, in time, became nothing

But a lying-ass song

Sung to the woman he failed.

Published on June 14, 2016