Intruder

by Jill Bialosky

reviewed by Diann Blakely

The angel-filled St. Bonaventure Cemetery, made famous by John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, contains the grave of Conrad Aiken, friend of T. S. Eliot at Harvard and beyond, winner of the Poetry Society of America’s first Shelley Award, and now best known for his frequently anthologized story “Silent Snow, Secret Snow.” At the age of eleven, Aiken watched his physican father kill his mother, then himself. The two are entombed together in standing cenotaphs and Aiken’s own memorial, a bench set at a right angle, bears the inscription “Give my love to the world” and “Cosmos Mariner—Destination Unknown.” The aforementioned story concerns a child’s descent into madness, which is represented by his retreat into an oneiric realm of ever-mounting snow.

Aiken’s hometown and final resting place, Savannah, doesn’t receive much snow, unlike Cleveland, Ohio, and this particular form of precipitation flurries and blizzards throughout the work of native Ohioan Jill Bialosky. “Fathers in the Snow” is one of the most powerful poems in her first collection, The End of Desire; her first novel is titled House Under Snow; last April, for Poetry Daily’s series of National Poetry Month features, she published a commentary on Stevens’ “The Snow Man”; and Intruder, her newest volume of poems, contains several works, perhaps most notably the non-rhyming, decasyllabic sonnet sequence “The Skiers,” in which snow joins the dramatis personae who comprise Intruder.

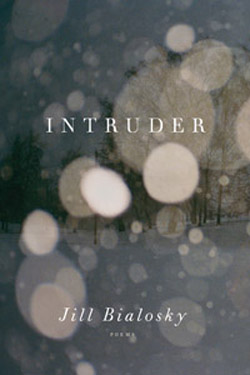

Bialosky has said in an interview in Poems Out Loud—which begins with a long question about the way snow acts as a leitmotif in her work, with asides about Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” and the snow-blotched appearance of the cover—that “a snow-filled mountain is almost a character in the poem.” Shelley’s “Mont Blanc,” and the terror its whiteness evokes in him, are brought to mind as well. And the reader is alerted to what is to come (“The Skiers” is Intruder’s literal and figurative center) by the prefatory poem, “Demon Lover,” an allusion to Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” in which a woman “wail[s] for her demon lover.” Here Bialosky begins with an italicized question, meaning it’s being asked by an Other, and closes with a near-koan about the nature of desire, which can intrude into our lives as an angel or its opposite: “Will you stay with me? / I won’t leave, she said. / “I must go now.”

The question arises: where is the line between angel and demon, madness and mystery? Bialosky clearly has both human feet planted on dry, non-slippery ground, being a wife, mother, teacher, and editor at W. W. Norton, and yet her elusive, subtly erudite work as a poet transports her to another realm entirely. In fact, there’s an aura of dissociation in many poems in Intruder, with Bialosky referring to herself as “The Poet,” particularly in those poems that feature her son. But dissociation is part of motherhood: that oneness shared when the child is nestled in the mother’s womb can also cause a sense of separation, of otherness from oneself. In “The Poet Contemplates the Nature of Reality,” Bialosky asks “What is my life?” “For months she lost / herself in work,” she continues, “Freud said work is important / as love to the soul—and at night she sat with a boy, / forcing him to practice his violin, helping him recite his notes.” “Good boy,” says the mother in “Music Is Time,” “See how hard you have to be on yourself? / How will your violin know who you are / unless you make it speak?” Perhaps most poignantly—and universally—this theme is further explored in “Rules of Contact,” which takes place at a Little League game and addresses not only the relation between mother and son, but also its inevitable disruption: “My son won’t let me kiss him anymore, / a mother in the bleachers cries.” These are some of the most psychologically astute poems about being a mother, and especially about being the mother of a son, since Plath’s.

Bialosky says, in the Poems Out Loud interview, that she’s “got to quit writing about snow!” But as someone who has lived half her life in states containing all four of America’s poisonous snakes (rattlers, cottonmouths, copperheads, and coral snakes, not to mention snapping turtles and clouds not of snow but rapacious, maddening stinging insects), I’m reminded of Hamlet’s remark about his father’s ghost: hic et ubique. What’s here and everywhere is here and everywhere. So let’s hope she doesn’t keep her resolution. Too many Bialosky poems of the rich and strange variety have emanated from snow, whether in Cleveland, New York, or Colorado.

Published on March 6, 2015