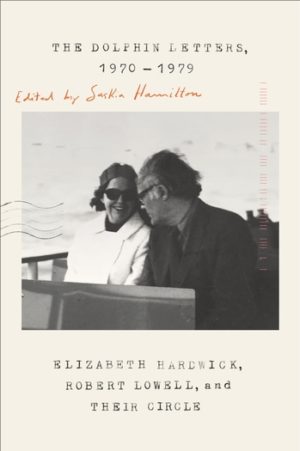

The Dolphin Letters, 1970–1979

by Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Lowell and their Circle, edited by Saskia Hamilton

reviewed by Heather Clark

“Art just isn’t worth that much.” So Elizabeth Bishop famously admonished Robert Lowell for lifting passages from Elizabeth Hardwick’s letters, without Hardwick’s permission, in his 1973 poetry collection The Dolphin. The book chronicled the breakdown of Lowell’s marriage to Hardwick and his new life in England with Lady Caroline Blackwood, ex-wife of Lucian Freud and heir to the Guinness fortune. Lowell dedicated The Dolphin to Blackwood, whom he portrayed as a life-awakening muse, while Hardwick seared his conscience from across the Atlantic.

The Dolphin pushed Lowell’s truth-telling style to its extreme. Some of his closest friends warned against publishing it, but he went ahead anyway. He wrote to Bishop, “My sin (mistake?) was publishing. I couldn’t bear to have my book (my life) wait hidden inside me like a dead child.” To publisher Robert Giroux, he brushed aside the morality of using Hardwick’s letters: “the real trouble for Lizzie is the picture of Caroline [ … ] I did everything I could to make my book inoffensive kind without killing it.” Lowell’s public humiliation of Hardwick shocked the literary world and pitted him against longtime allies such as Bishop, Adrienne Rich, and Mary McCarthy. “Anyone’s, everyone’s, sympathy is entirely with you,” Bishop wrote to Hardwick shortly after the book’s publication. “It has hurt me as much as anything in my life,” Hardwick responded.

Nearly fifty years later, The Dolphin seems less incendiary. The book’s protagonists are dead; its heartbreaks and wrongs muted. It reads as a well-made sonnet sequence about love lost and gained, by turns self-pitying and lyrical. There are moments of beauty, but its privileged male perspective, especially in the “Mermaid” poems, feels dated. We want to know, now, about the brilliant woman whose words were used against her.

In Saskia Hamilton’s extraordinary edition, The Dolphin Letters, 1970–1979, Hardwick is unmistakably the heroine. Her voice is stronger, more sympathetic, and, finally, more interesting than Lowell’s. Hamilton has chosen letters that illuminate The Dolphin controversy not only between Lowell and Hardwick, but amongst others in their literary circle, including Bishop, McCarthy, Rich, Blackwood, Giroux, Charles Monteith, Robert Frank Bidart, and Blair Clark. The result is a page-turning drama that doubles as one of the most important and illuminating epistolary collections of the twentieth century. These letters bring us back to the moment when “confessionalism” had reached what seemed like a dead end. They reveal not only support for a wronged woman, but suspicion of an aesthetic gone off the rails.

The heart of this book is the love story between Lowell and Hardwick. The letters begin a little more than two decades into their marriage, when Lowell moves to Oxford for a visiting fellowship at All Souls College. He falls in love with Blackwood and all but stops replying to Hardwick’s letters. Lowell often had affairs during his manic phases, and Hardwick begins to suspect that he has found another “girl.” She tries to bring her husband to his senses. “You are a great American writer [ … ] You are not an English writer, but the most American of souls [ … ] You are a loss to our culture, hanging about after squalid spoiled, selfish life.” When Lowell writes to Hardwick of Blackwood’s pregnancy—their son, Robert Sheridan Lowell, would be born in September 1971—he tells her, somewhat smugly, that the baby will be a “Lowell-Guinness.” The marriage is over.

Hardwick struggles, throughout these years, to maintain her dignity as she keeps herself and her daughter Harriet afloat in New York. She is a sympathetic and deeply competent mother, compensating, perhaps, for Lowell’s absenteeism. She organizes Harriet’s school and summer camp schedules, writes for the New York Review of Books, pays the bills, answers Lowell’s mail, organizes Lowell’s archive for sale, and persuades Lowell, over and over, to pay his taxes. The letters reveal—as if there were any doubt—how much Hardwick kept Lowell’s life ticking, even after he had left her for Blackwood. She has a hard time condemning him: she excoriates him for his ruthlessness in one letter, only to apologize for her bad humor in the next. Sometimes these vacillations take place within the same letter. In 1971: “Mary [McCarthy] has written me many times how much better off I am. Everyone insists that I am. But can it be true?” A few sentences later: “You will never be free of the dreadful thing you have killed in yourself and of your ingratitude and lack of loyalty and love. And no child you produce can be more splendid than the one you abandoned.”

Any remaining goodwill dissolves after the publication of The Dolphin. Taxes are a surprisingly revelatory theme. After Lowell complains to Hardwick, in 1973, that he is “catatonic” before his income tax forms, she explains from New York, as if speaking to a child, “This is a thing that will go on until you die and so I guess this year is the time to get in touch with it. No one, Cal, writes you about filing your income taxes; you have to ask an accountant to do it.” Three weeks later, with no sign of progress, Hardwick writes, “you have not been able to get a simple paper about your income tax for the last year sent here. A deed every citizen has to do every year of his life. I am bewildered.” Negotiations over the sale of Hardwick’s house in Maine quickly fall apart when Lowell and Blackwood try to stop the sale. (“I can’t sign away something that might be Sheridan’s inheritance,” Lowell writes her.) Letters and telegrams that had been civil, even generous, become ugly. Lowell and Blackwood’s meddling in her house, on top of The Dolphin, is too much for Hardwick. She writes Lowell in 1973, “I am near breakdown and also paranoid and frightened about what you may next have in store, such as madly using this letter. I do not wish to write you again. Your life is your own and has nothing to do with me.” Indeed, the tone of Hardwick’s letters to Lowell changes after this point. “There is not much news,” she writes to him indifferently in July 1974. “New York is not unpleasant and I have been in and out a lot but I look forward to the month of August in Castine.” Hardwick would not let her epistolary guard down to Lowell again.

In 1977, Lowell suffered a fatal heart attack in a New York taxi on his way to Hardwick’s apartment. He was clutching a portrait of Caroline Blackwood when he died. The circumstances of his death symbolized the unresolved nature of his love for both women. Hardwick remained unresolved, too. In Maine the following summer, she wrote Bishop, “Cal seemed to be about everywhere: his red shirt and socks were a painful discovery. The death is unacceptable and yet I know he has gone and it is very difficult to bring the two together.” Loving and losing Lowell was something Hardwick had to bear many times. The Dolphin Letters reveals how very difficult it always was.

Published on May 19, 2020