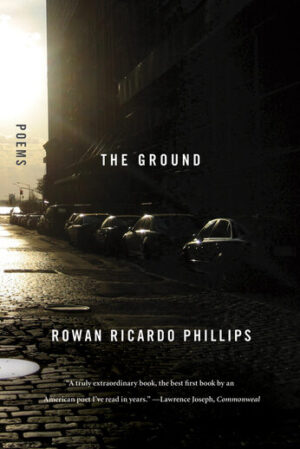

The Ground: Poems

by Rowan Ricardo Phillips

reviewed by Heather Treseler

Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s first collection takes as its epigraph unusually exultant lines from the Book of Job: “Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? . . . When the morning starres sang together, and all the sonnes of God shouted for joy?” These divine interrogations reframe the question acquaintances often pose to one another in order to locate themselves in relation to a historically defining event: Where were you when X occurred?

The Ground takes 9/11 as its catalyst, transforming it from a generation’s axis of fear and despair to a crisis that can be accommodated within the ambiguity of poetic gnosis. Indeed, Phillips proves that acts of terrorism can be written downward without melodrama or agitprop. His “Song of Fulton and Gold” bears as its refrain “The eye seeking home / has to lower / lower / lower,” a solacing iteration cinched closed by the final couplet: “There are no / towers.” Yet Phillips also takes that day’s blanked sky as merely one event in the city’s advent: an arrival paralleled by the birth and reach of a poet’s consciousness, the true subject of the book’s sounded gravity.

“Tonight” introduces the collection’s forty-four poems, which journey from Harlem to Hades and from Stockholm to St. Petersburg as an urban Orpheus names the features in his City of Man. Tracing the skin of his birthplace, the speaker tutors his reader in the subtle art of haptic reconnaissance.

In the beginning was this surface. A wall. A beginning.

Tonight it coaxed music from a Harlem cloudbank. It freestyled

A smoke from a stranger’s coat. It stole thinned gin.

It was the edge of its beginnings but outside

Looking in. The lapse-blue façade of Harlem Hospital is

weatherstill

Like a starlit lake in the midst of Lenox Avenue.

Tonight I touched the tattooed skin of the building I was born in

And because tonight is curing the beginning let me through.

And everywhere was blurring halogen. Love the place that

welcomed you.

Modifying the schema of a Spenserian stanza with a secondary chorus of internal rhymes (“thinned gin” and “halogen”), Phillips invites us into the sonic materiality of this conjured scene. A tableaux emerges from the staccato first line, one choreographed with Joycean portmanteau words (“weatherstill”) and allusions to the gospel of John. Cloud music, borrowed smoke, and stolen gin fuel the “freestyled” energies of this seeming improvisation: a jazz set staged within the adapted strictures of a sixteenth-century form.

Throughout The Ground, Phillips recasts poetic forms in his own métier, a method that finds its metaphor in the medial lines of “Tonight.” Here, potential energy gathers on the periphery “outside / Looking in” as the speaker limns the Harlem Hospital, “lapse-blue / . . . Like a starlit lake” on Lenox Avenue, phrases that recall the lapis lazuli of Yeats’s prized sculpture and the waterways of the Romantics’ lake district. But while Yeats and Keats’s coterie vested art objects and pastoral landscapes with mystical qualities, Phillips finds his restorative locus amoenus in the heart of Harlem. Given the “curing” of the night—its healing, its preservation, its preparation for use—the speaker can travel “through” to his beginning, one inscribed on the epidermis of buildings and lit by the iodine glow of streetlights’ “blurring halogen.”

In tracing the “tattooed skin” of his birthplace, Phillips suggests that the classical doxa poeta nascitur non fit (the poet is born, not made) may indeed describe the mysterious interaction of geography and sensibility or what generates the subconscious catalysts of imaginative will. In the words of Michael Harper, a mentor Phillips and I shared at different intervals, “You don’t choose to be a poet; poetry, for better or worse, chooses you.” For Phillips and for Harper, poetry is a constitutive music with tonic medicinal powers; it is also, for both, an intensifying register in which history can be meaningfully amplified, remixed, or rendered mute. In “Terra Incognita,” Phillips writes “I plugged my poem into a manhole cover / That flamed into the first guitar . . . / And made from where there once was / Ground a sound instead to stand on.” Taking the sonic underground of city streets as his instrument, the poet restyles Stevens’s blue guitar as an urban lute, one capable of resurfacing the metaphysics of the real.

This trope repeats, hauntingly, in a four-poem sequence about Eurydice and Orpheus’s ill-fated honeymoon in Hades and, subsequently, in a riveting pair of poems that measure Orphic music in its somatic score. In “Aubade: Jardins de Walter Benjamin” and “Aubade, Vol. 2: the Underground Sessions,” travelers return from their subterranean tours of the nightclubs of Barcelona and New York, the cities that are Phillips’s own seasonal homes. In the first “Aubade,” young habitués of nightclubs emerge “plumed, perfumed palimpsests . . . / Wasp-waisted . . . / Some snow fed and fiddled with; some searching their cells for significance,” while, in counterpoint, old veterans, “still cardiganed, still propped by canes,” argue politics in a nearby park. While the younger set searches for their cellular “significance” on the airwaves or in their own vital biology, an old veteran “curses in Catalan the shrapnel / Deep in his hip.” Here the “cells” of the young—their phones, their biological matter, their imprisoning desire—contrasts with the wounded leg of the aged revolutionary, who once made his own furious dance for a Republic that has ceased to exist.

In the classical telling of Orpheus and Eurydice, music teases the dead into near-existence, trawling desire from a dead land. Yet, in Phillips’s version, it can also be rejected by those who resist its thrall. In his “Double Death of Orpheus,” Eurydice withdraws instinctively from the “slaver in his [Orpheus’s] heart” as he “grew consumed with little things . . . / The second time he lost her.” Similarly, in the second “Aubade,” a club dancer—remembering his or her freedom at the level of breath and twitch—flees the lulling sonic “womb” before daylight arrives, an escape that cannot be enacted by Caesar’s “collared deer,” or those who remain within the bounds of their accepted captivity.

Remixing myths, poetic forms, and defining moments in imperial history, Phillips poses questions about will and desire, domination and mutuality, mortmain and futurity that can only be answered by the negative capability of poetic language. An amethyst key to the collection is the strange poem “Golden,” which first appeared in The New Yorker; its tercets rework the dyadic exchange between lovers, “changing the gender,” as the poet Robert Hayden once advised, such that the giver and the recipient, the gift and its erotic trace, the “bee” and its “luckless clover” appear to merge into the third property that the skillful can render as art. Drawing from a decade of publication, Phillips’s Ground signals the arrival of a major voice that will not submit to its inheritance or mimic the integrity of any but itself.

Published on October 28, 2013